With a new season of baseball upon us and what I regard as the real start of spring, it’s an opportune time to look back at Pennsylvania’s rich baseball history.

Pennsylvania has been a part of baseball from the beginning with the Philadelphia Athletics’ participants in the first professional season in 1876 with the creation of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs.[i] The Athletics were removed after the first season, but two other professional Pennsylvania teams emerged in the 1880s—The Philadelphia Phillies, founded in 1883 and now the oldest, continuously operating franchise in sports that has not changed its name or city affiliation, and the Pittsburgh Pirates founded in 1886.[ii]

At the turn of the 20th century, the American League was founded and, despite early animosity, the two leagues entered into an agreement to allow for an interleague championship in 1903, laying the foundations for Major League Baseball (MLB) as we know it today.[iii] The Pittsburgh Pirates represented the National League in that first World Series, but they lost to the Boston Americans.[iv]

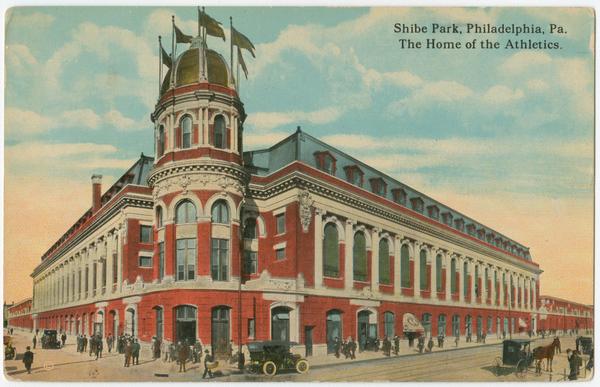

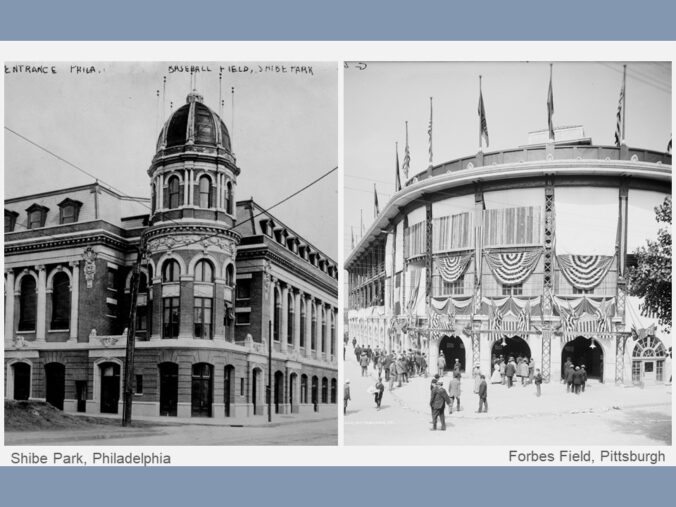

Shibe Park was home to the Philadelphia Athletics’ from 1909-1954, when the team relocated to Kansas City, and the Philadelphia Phillies from 1938-1970. Photograph courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia, https://www.librarycompany.org/.

The development of the two-league system set the stage for new trends in baseball stadiums. The Philadelphia Athletics, or A’s, joined the American League when it began in 1901. The A’s had early success, which drove demand for tickets beyond what their first ballpark, Columbia Park, could accommodate.

The A’s owner, Ben Shibe, and manager/part owner Connie Mack began planning for a new stadium in 1907 and engaged William Steele & Sons for construction.[v] The result was a spectacular, French Renaissance style ballpark ready to dazzle for opening day on April 12, 1909. Shibe Park, later Connie Mack Stadium and shared home with the Phillies, is recognized as the first ‘Jewel Box’ ballpark—a type characterized by highly ornamented façades oriented snugly within the city grid.

Sadly, most Jewel Box ballparks have disappeared, but the style experienced a revival in the early 2000s as many teams returned to their city’s downtowns, which they had vacated in the 1960s and 70s.[vi]

When Shibe Park opened in 1909, most attendees wore suits and bowler hats, a stark contrast to the jerseys and baseball caps worn at most 21st century games. Source: Bain News Service, Publisher. Shibe Park, Philadelphia baseball. , 1914. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014697779/.

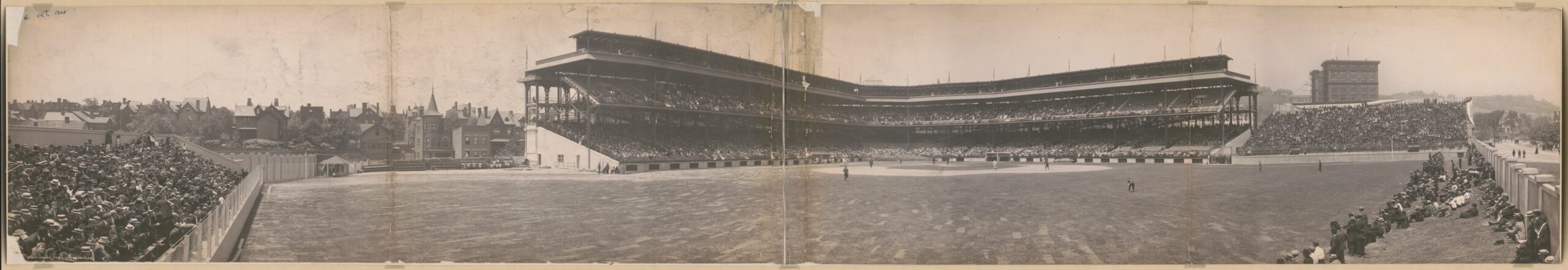

1909 turned out to be a memorable year for baseball in Pennsylvania, as the Pirates also opened a new stadium—Forbes Field, the first stadium constructed entirely of poured concrete and steel. Forbes Field combined features that few other ballparks of the time could boast such as a three-tiered grandstand, ramps to each level, and elevators to the third level’s luxury boxes—features found in most baseball stadiums today.[vii]

In its inaugural season, Forbes Field would be a part of many firsts for the Pirates, who won a franchise best 110 games and squared off against the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. The fall classic pit two hall of famers, Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb, against one another and, after going to a full seven games, the Pirates took home the franchise’s first World Series victory.[viii]

The three tiered grandstand at Forbes Field was one of the remarkable interior features of the ballpark. This panoramic photograph shows the expansive outfield and gathering of fans in the rise before the wall that became necessary in the 1920s. Source: Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, PA. Pennsylvania Pittsburgh, 1908. [United States: Detroit Publishing Co] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015649146/.

The Grays played many games at Forbes Field—though they would go on to split their time between Pittsburgh and Washington D.C.[x] In 1945, the Grays played the final game of the Negro Leagues World Series at Shibe Park, which they lost to the Cleveland Buckeyes.[xi]

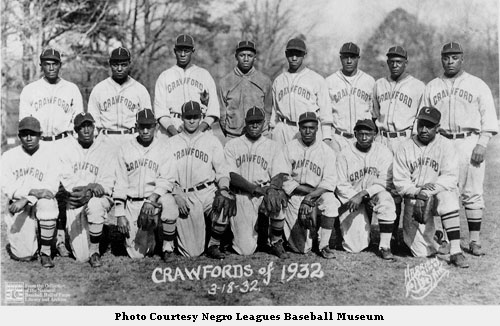

Though short lived, the crosstown Pittsburgh Crawfords, backed by Crawford Grill owner Gus Greenlee, had teams stacked with future hall of famers ‘Cool Papa’ Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, and Satchel Paige, making them a major attraction for Pittsburgh’s baseball lovers.[xii]

The 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords were a barnstorming team that played exhibition games only. The Crawfords would join the Negro National League in 1933 when it was founded by the Crawford’s backer Gus Greenfield. Photograph courtesy of Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, https://nlbemuseum.com/nlbemuseum/reslib/phototeam.html.

Tied together in history, both Forbes Field and Connie Mack Stadium/Shibe Park held their final games in 1970. By this time, both stadiums had fallen plague to changing winds in baseball, leading their teams to build stadiums elsewhere.

The Phillies—who became tenants at Shibe Park in 1938 and assumed ownership when they A’s left for Kansas City for the 1955 season—would move to South Philadelphia’s Veteran’s Stadium. Shibe Park remained standing until 1976 and today the only vestige is a historical marker on Lehigh Avenue to note its location.[xiii]

The Pirates abandoned Forbes Field during the 1970 season when construction on Three Rivers Stadium was completed. A portion of the outfield wall remains standing. The legacy of Forbes Field’s technological advances is still present in modern stadiums.[xiv]

Although little remains of these historic buildings, they made their mark on American history as witnesses some of baseball’s greatest players and feats. If you tune in to games this spring, remember some of Pennsylvania’s baseball history!

________________________________________________________

[i] “Philadelphia Athletic Team History & Encyclopedia,” Baseball Reference, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/ATH/; “Year in Review: 1876 National League,” Baseball Almanac, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/yearly/yr1876n.shtml.

[ii] “Timeline – 1800s,” Philadelphia Phillies, https://www.mlb.com/phillies/history/timeline-1800s; “The Early Years,” Pittsburgh Pirates, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.mlb.com/pirates/history/timeline/early-years.

[iii] “Postseason History: World Series,” MLB.com, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.mlb.com/postseason/history/world-series.

[iv] “Postseason Results,” Pittsburgh Pirates, accessed January 31, 2023, https://www.mlb.com/pirates/history/records-stats-awards/postseason-results.

[v] “A Short History of the Philadelphia Athletics,” Oakland Athletics, https://www.mlb.com/athletics/history/philadelphia-athletics.

[vi] Some good examples of the revival style include Camden Yards, Busch Stadium, and Comerica Park. James Lincoln Ray, “Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium (Philadelphia),” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed January 25, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/connie-mack-stadium-philadelphia/; “Architect Breaks Down Iconic Baseball Stadiums,” Architectural Digest, posted August 23, 2022, accessed January 25, 2023, https://youtu.be/3OkSW5qV7jQ.

[vii] Ron Baraff, “The Origins of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field,” Rivers of Steel, June 17, 2021, accessed January 30, 2023, https://riversofsteel.com/dreyfuss-folly-the-origins-of-pittsburghs-forbes-field/; “Forbes Field,” ballparksofbaseball.com, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.ballparksofbaseball.com/ballparks/forbes-field/; “Aerial View of Forbes Field,” Historic Pittsburgh, accessed January 30, 2023, https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt:MSP285.B022.F03.I06.

[viii] Honus Wagner and Ty Cobb were in the first Baseball Hall of Fame Class in 1936. The other players elected were Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, and Babe Ruth. “1909 Pittsburgh Pirates Statistics,” Baseball Reference, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PIT/1909.shtml; National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed January 30, 2023, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-fame/hall-of-fame-explorer.

[ix] Baseball was segregated until 1947, but African Americans developed their own professional baseball, the Negro Leagues. Rob Ruck, “On the 100th Anniversary of the Negro Leagues, a Look Back at What Was Lost,” JSTOR Daily, February 19, 2020, accessed January 31, 2023, https://daily.jstor.org/100th-anniversary-negro-leagues-look-back-what-was-lost/.

[x] “Homestead Grays,” MLB.com, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.mlb.com/history/negro-leagues/teams/homestead-grays.

[xi] The Negro Leagues World Series was not considered the Leagues’ premier event and was often impractical to host as it was not uncommon for one of the leagues to be defunct by season’s end. The most popular Negro Leagues event was the East-West Game which was the equivalent of the All-Star Game. The East-West Game occurred between 1933 and the Leagues’ last season in 1962, but it never took place in Pennsylvania. “Negro World Series,” Baseball Reference, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Negro_World_Series; “East-West Game,” Baseball Reference, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/East-West_Game.

[xii] Rob Ruck, “On the 100th Anniversary of the Negro Leagues, a Look Back at What Was Lost,” JSTOR Daily, February 19, 2020, accessed January 31, 2023, https://daily.jstor.org/100th-anniversary-negro-leagues-look-back-what-was-lost/, “Satchel Paige,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, accessed January 30, 2023, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/paige-satchel; “Pittsburgh Crawfords,” MLB.com, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.mlb.com/history/negro-leagues/teams/pittsburgh-crawfords.

[xiii] James Lincoln Ray, “Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium (Philadelphia),” Society for American Baseball Research, accessed January 25, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/connie-mack-stadium-philadelphia/; “1945 Negro World Series,” Baseball Reference, accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/1945_Negro_World_Series.

[xiv] “Aerial View of Forbes Field,” Historic Pittsburgh, accessed January 30, 2023, https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt:MSP285.B022.F03.I06.

The Hilldale Athletic Club (1925 Negro League World Series) and the Pittsburgh Keystones (1887) had Hall of Fame players including Judy Johnson, Oscar Charleston and Sol White.