As the sun emerges, temperatures rise, and travel restrictions ease, consummate travelers begin to get itchy feet. This spring, the National Road Heritage Corridor invites you to exit the highway and take the time to explore some of Pennsylvania’s nation-shaping history and the historic places along the Historic National Road.

“The Road That Built America”

In 1806, the US Congress passed and President Thomas Jefferson signed legislation enabling the construction of the nation’s first multi-state, federally funded highway – the Cumberland Road, which would become known as the National Road.

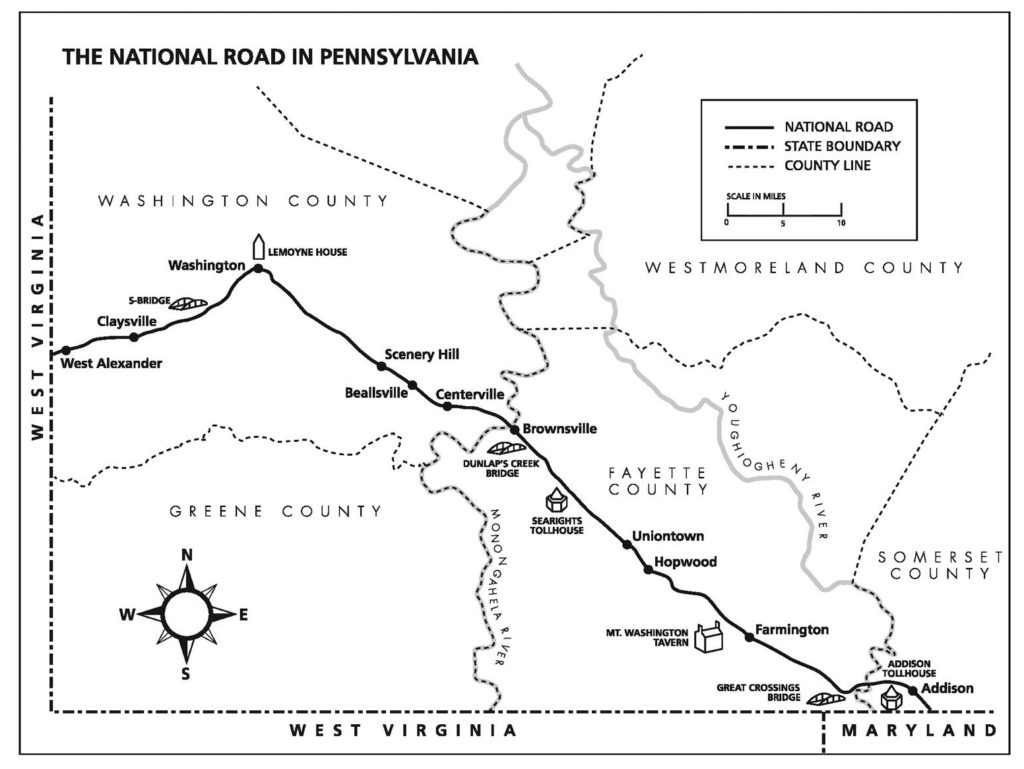

Constructed between 1811 and 1837, the original National Road runs from Cumberland, Maryland to Vandalia, Illinois (the state capital in 1837). The 90 miles of the Road that cuts across the southwest corner of Pennsylvania is one of the state’s twelve Heritage Areas and paves a path through some of the most important, course-changing events of early America’s history.

It is the birthplace of the French & Indian War – the conflict that ignited America’s fight for independence, and the seat of the Whiskey Rebellion, where the federal authority of the United States was first tested. Coupling history with stunning scenery, unmatched architecture, and charming small towns, the National Road offers many ways for the curious traveler to broaden their perspectives and connect with the past.

It is because of this combination of archaeological, cultural, historic, natural, recreational and scenic qualities that the National Road was named a federal All-American Road in 2002. To receive this designation, a road must possess multiple intrinsic qualities that are nationally significant and have one-of-a-kind features. The road or highway must also be considered a “destination unto itself,” meaning that travelers seek it out just for the experience of driving it.

The National Road Heritage Corridor is very proud of this well-deserved designation, but it also is honored with another, earlier one. In 1976 the American Society of Civil Engineers designated the National Road as a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark as the Road was the precursor of today’s federal interstate system and represented the highest standards of road design and construction of the time.

Is It the National Road or Route 40?

The National Road is often referred to as Route 40, and the two roads do share a path much of the time. However, the National Road was largely hand dug and builders had to work within the limitations posed by construction techniques and the mountainous terrain. As described in the comprehensive history The National Road, the process of building the road was arduous and labor intensive:

“Burly axmen began the construction process by felling all trees along a clearing sixty-feet wide through the forest. They were followed by choppers, grubbers, and burners, whose work might take weeks to complete in heavily timbered sections…After grubbing, the road had to be leveled by pick-and-shovel wielding laborers. This earth-moving army cut into hillsides, flung tracks of fill across hollows, and hauled away excess earth and rock. Finally, the graders, stone crushers, and pavers laid the roadbed.” The stone crushers broke the rocks into pieces with long-handled hammers until the pieces were small enough to fit through either a seven inch or a three inch sized ring, depending on which layer of the road it was for.

The hilly landscape of the western frontier also shaped the path the road would take. Horse drawn carriages, coaches, and wagons could not travel up the steep grades of the hills, so the route needed to weave between rises and stick to low lying areas. Where it was necessary to traverse and incline, switch-backs were constructed to keep the grade at a minimum.

When Route 40 construction began in 1926, those engineers did not face the same restrictions. The road was straightened to make a more direct route. In the process, portions of the old National Road were bypassed.

A sharp eye will soon learn to spot the places where the National Road and Route 40 separate, and the cast iron markers will dot the north side of the road at every mile. If you prefer more modern directions, National Road signs point the way too.

The Craftsmanship of Infrastructure

Beyond the construction of the road itself, the Civil Engineering Landmark designation also honors the way craftsmen navigated the creeks and rivers in the road’s path. One of the more unique engineering features of the National Road are the “S Bridges.” These bridges are called such because when viewed from above they resemble an “S.” The unusual shape of these cut stone bridges was to allow water to pass more easily under the arches and to limit erosion of the stone.

One example in Pennsylvania is located where the National Road crosses Buffalo Creek near Taylorstown at PA 221. Though the S Bridge is no longer open to vehicles, visitors are able to park nearby and walk on the now grass-covered surface. This intersection also shows how the National Road was “straightened” as part of the Route 40 construction.

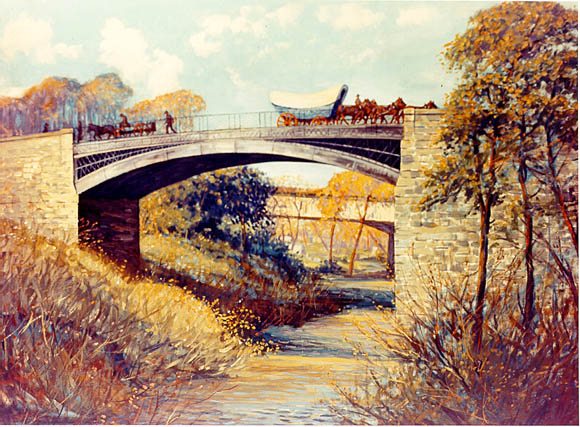

The other bridge of note is the Dunlap’s Creek Bridge in Brownsville, Fayette County, which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Built in 1839, this small but mighty structure is the first cast iron bridge built in the United States. Not only was Dunlap’s Creek Bridge the first cast-iron bridge in America, it was the first metal bridge anywhere to use what its builder, Captain Richard Delafield, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, described as “standardized, interchangeable, manufactured parts.”

The bridge was built as part of the federal government’s effort to make repairs on the National Road before handing authority over to the states. Dunlap’s Creek at Brownsville was an especially troublesome crossing as three bridges had already been destroyed since 1801. In defense of his unusual plan, Delafield wrote to Brigadier General Charles Gratiot, Chief Engineer:

“In the estimates of the services of the year I have asked an appropriation for a cast iron bridge for Dunlap’s Creek, induced so to do from the circumstance of finding no durable stone that will resist the thrust of the arch required to span the creek (100 feet) preferring it to a wooden structure, perishable from the decay of the timber, and exposed to fire, a risk more hazardous than with the many excellent structures of the kind throughout the country, from the circumstances of there being no guard or toll keeper to prevent travelers carrying fire through and upon it.”

Captain Delafield’s plan proved farsighted– after 183 years, the bridge is still in use and carries vehicle traffic with no weight restrictions. Dunlap’s Creek Bridge is a testament to American ambition and ingenuity and a full restoration of this marvel is planned for 2023.

The Historic National Road is a fascinating paved timeline of American history and you can learn more with the National Road Heritage Corridor. For travel tips, history bits, and more stories from the region, follow us on social @NationalRoadPA and stay tuned for a brand new experience at nationalroadpa.org.

Today’s Guest Contributor is Sarah Collier, Executive Director of the National Road Heritage Corridor.

My great grandfather Robert Brownlee was a toll collector on the National Road. While out collecting in 1906 he had a stroke and died but stayed on his horse while the horse carried him home.

Sorry but I misspoke and looked up my family history. His obituary says he was a National road commissioner and was out looking at improvements when he had his stroke. This was September 23, 1902.