September is National Preparedness Month. According to the PA Emergency Management Agency (PEMA), this year’s theme is “Disasters don’t wait. Make your plan today.”

Continue reading

Blog of the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office

September is National Preparedness Month. According to the PA Emergency Management Agency (PEMA), this year’s theme is “Disasters don’t wait. Make your plan today.”

Continue readingOn October 3rd, 2018, the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (PA SHPO) hosted a demonstration workshop to explore resiliency options for Mather Mill, a National Register–listed gristmill constructed ca. 1820 in Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County.

The workshop was conducted as part of PA SHPO’s Disaster Planning for Historic Properties (DPHP) initiative, a program developed with a grant from the National Park Service that is made available to states impacted in 2012 by Hurricane Sandy.

This demonstration workshop provided an opportunity for PA SHPO to narrow its focus. The office invited architecture and planning firms from throughout the region to attend a one-day workshop dedicated to learning about a single, specific property—its particular history, risks and opportunities—and brainstorm possible resiliency solutions and ways to scale them to other at-risk properties.

Mather Mill, our target property for this workshop, is a Commonwealth-owned property in need of a new use. It’s also representative of a common property type that is, by definition, near and potentially at risk from water. Both the mill and nearby properties are in the 100-year floodplain, and the mill has flooded several times since the Commonwealth acquired it in 1966. The Commonwealth plans to eventually transfer ownership of the property but no specific client or program currently exists.

A property immediately across Mathers Lane that was recently acquired by Whitemarsh Township was included as part of the workshop’s scope. After two flood-prone buildings were demolished, the property is now subject to Federal Emergency Management Agency deed restrictions that require it to remain as open space. This does allow for some minimal development supporting continued use of the property as open space.

The day of the workshop started with an introduction to the DPHP program from PA SHPO director Andrea MacDonald. Presentations included a brief overview of the National Park Service’s standards and guidelines for rehabilitating historic properties, contextual background on the Wissahickon Valley Watershed, and floodproofing techniques and how they might impact historic properties.

In addition to the subject matter experts who gave presentations, a few more people were available for an afternoon discussion:

The quality of a discussion like this is a direct result of the people involved, and they provided a valuable source of information that had not been specifically addressed in the morning presentation.

Following the workshop, the firms were given two weeks to create design proposals for use and resiliency at Mather Mill and suggest strategies for scaling those proposals to other at-risk properties. The firms were given substantial format flexibility. We wanted to see a variety of design approaches, visual styles, and ways of prioritizing the issues at play.

PA SHPO received materials from five firms:

To learn more about the Mather Mill designs, check out its record in our online CRGIS system. All six proposals are uploaded and available.

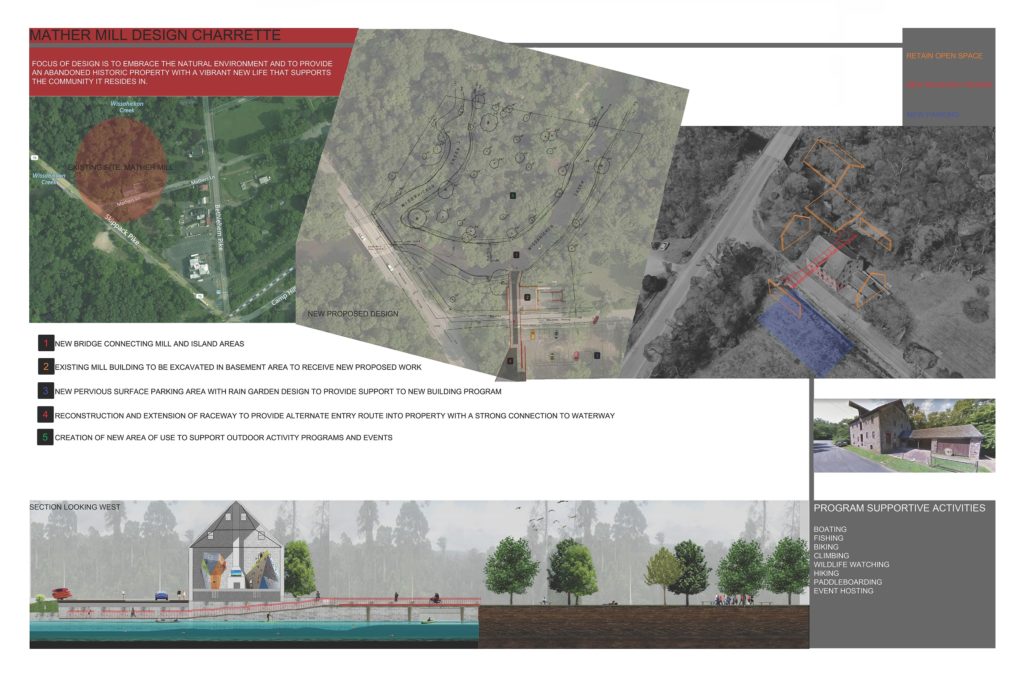

In addition to the participating firms, Shawn Massey, Architectural Designer here at the SHPO, also produced a design proposal. Here is what he had to say:

“The focus of my design board of Mather Mill was to reconnect the once thriving physical partnership of the neighboring waterway back with the abandoned mill. My design reopened the raceway so the water of the Wissahickon Creek could once again occupy the mill in a way that would create new experiences for the supportive users. This new revived raceway and creek way would be dug deeper so that boaters, fishermen, and other water activity enthusiasts could interact with the mill in a unique new way. This raceway would be an entry/rest/exit point for the users of the creek, site, and building, while also starting to deal with the flooding issues that put a dark cloud over the site.

Another part of the design was a new pervious parking lot across the street that would support the above-mentioned new circulation points along with making it much safer to access the mill and the surrounding land. The design also included a bridge from the mill to reconnect the neighboring island area to allow for outdoor activities and events.

Not only did the design deal with natural environment factors but it also gave Mather Mill a supportive interior program. The interior was proposed in the design to be a community gathering space where climbing walls, skateboard ramps, and other public events could be held. This would allow the mill to retain its existing open space with minimal edits to the historic structure. I believed with support from the surrounding community organizations this may be a viable use for a historical mill that needs to be brought back to life.”

In November, the proposed materials were presented to the public at an open house event in Whitemarsh Township.

While the question of how to scale resiliency solutions received less focus than solutions specific to Mather Mill, it remains PA SHPO’s central concern.

Later this month, PA SHPO will be partnering with the City of Philadelphia on a second workshop in the city. A second workshop allow us to continue exploring these solutions. Keep an eye out for more information; we will be scheduling a public open house for later in the year to showcase the results of our second workshop. The best way to be “in the know” about opportunities like our open houses is to sign up for our e-news.

John Gardosik manages the Disaster Planning for Historic Properties Initiative for the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office. Shawn Massey is PA SHPO’s Architectural Designer.

In the last installment about the ongoing Disaster Planning for Historic Properties Initiative we focused on survey work in the City of Harrisburg. Since that time, the survey teams led by Commonwealth Heritage Group and ASC Group have moved on to other communities in Dauphin County.

Located at the northern end of the county, Lykens Borough is home to a large number of properties that are both over 45 years old and located in the 100-year floodplain. The survey teams spent more than a week collecting flood elevation data on 227 buildings throughout the borough. While there, we met many residents who talked about Tropical Storm Agnes and how flooding from the storm changed the community in profound and lasting ways.

Continue readingMuch like the early settlers of Harrisburg, many of us today feel drawn to bodies of water, whether for their natural beauty, ability to fuel industries, or provision of vital resources to developing communities.

Continue reading

During the week of August 13th, The Pennsylvania Silver Jackets hosted floodproofing workshops in York, Lewisburg, and Wellsboro, and the State Historic Preservation Office had a representative (me) there to answer questions from public officials and members of the public.

Now I’m sure you have a lot of questions. What are Silver Jackets? Why was PA SHPO there? What are Flood Proofing Workshops? These are all excellent questions; let’s address them one at a time and look at some example of real-life flood proofing projects and their effects on historic resources.

Pennsylvania Silver Jackets

To quote the Silver Jackets website, the “Pennsylvania Silver Jackets is an interagency team dedicated to working collaboratively with the commonwealth and appropriate stakeholders in developing and implementing solutions to flood hazards by combining available agency resources, which include funding, programs, and technical expertise.”

Silver Jackets – multiple agencies, one solution!

Why the name? Different agencies have specific colors they use for their jackets during emergency response (think blue FEMA jackets after Hurricane Katrina), but nobody had yet claimed silver, so it serves as a unifying color for all agencies. Every state except for Hawaii has a Silver Jackets team, and Pennsylvania’s meets quarterly in Harrisburg to plan outreach and discuss project opportunities.

Community outreach is one of the Silver Jackets’ priorities.

Flood Proofing Workshops

Each day included two workshops – one in the afternoon for public officials and one in the evening for members of the public.

Floodproofing workshop in Lewisburg, Union County, on August 15, 2018.

In the world of emergency management, floodproofing measures are a subset of hazard mitigation and are divided into two general categories: structural and non-structural. These workshops focused on non-structural floodproofing methods. Somewhat confusingly, “non-structural” floodproofing measures include lots of projects that directly affect, alter, move, or even demolish existing structures.

Structural floodproofing includes projects that involve building something new, such as a dam or levee, while non-structural floodproofing includes projects that include no construction or alterations to existing buildings. Basically, non-structural floodproofing includes everything than an individual property owner can do to her property.

This can include planning, relocating utilities above projected flood levels, filling in a basement, elevating, or even relocating a building to remove it from flood risk.

Hufnagle Park in Lewisburg, PA

While in Lewisburg, I had some time between meetings to explore the borough (and look for something to eat.) Walking down Market Street, I passed Hufnagle Park and saw families strolling along a stream. As it turns out, this park is an example of a large hazard mitigation project to reduce flood risks by increasing open space along the stream.

Looking southeast along Bull Run in Lewisburg, PA in August 2018.

The Borough of Lewisburg collaborated with Bucknell University in 2004 to produce The Lewisburg Neighborhood Project, a plan to address a range of concerns including student housing availability and flood hazards. One of the central projects in the plan was the Bull Run Greenway, a system of parks, trails, and green spaces along a stream that runs through the borough.

In 2012 the Borough used federal funds to purchase and demolish ten private properties on 6th Street southwest of Bull Run that were at heightened risk of repeated flooding. These buildings were within the Lewisburg Historic District, so mitigation of this project was required in the form of recordation of the to-be-demolished buildings and their immediate context. In the photo above, the demolished structures would have been visible on the right-hand side. Below are some example photos provided in the recordation package.

Lewisburg’s 102 South 6th Street in 2012, now demolished.

Lewisburg’s 112 & 114 South 6th Street in 2012, now demolished.

This type of project is often referred to as “demolition-acquisition”, and it is perhaps the most permanent form of hazard mitigation that FEMA funds. No funds will ever have to be spent on these properties again, and, by converting the land to permanent open space, surrounding properties could benefit as well. When a property is acquired using FEMA funds, it is required to remain open or park space in perpetuity. The next time it floods, water from Bull Run will have a little more space to flow and might not have as much of an impact on the houses across the street. Of course, ten buildings are now gone forever.

Peer State Example

There are hazard mitigation measures that can have less of a negative impact on historic buildings, but sometimes they require an extra level of creativity to balance hazard mitigation requirements with historic integrity.

As an example from outside of the commonwealth, new owners of the old Spaghetti Warehouse building in Houston, Texas are embarking on major rehabilitation project. The building is a contributing resource in the Main Street Market Square Historic District, but it backs up to Buffalo Bayou and was damaged by Hurricane Harvey.

As shown in the rendering below, the project would actually open the building up to water; in future floods, the bayou will be able to flow right through the back and side wall. The only fully enclosed and condition space will be on the second floor, and even that will be set back from the two newly opened walls.

Rendering of proposed changes to 901 Commerce; Houston Planning and Development.

Despite these changes, the owner intends to make full use of 901 Commerce with a bar on the second floor and market space on the first floor and basement. Food trucks will even be able to pull directly into the basement. This is, of course, a pretty extensive alteration to this building, but it might provide a thoughtful alternative for how to live with water without losing our built heritage.

And that brings us back to three days of workshops in central Pennsylvania. Bull Run flooded in 2011 in Lewisburg, and Houston is still recovering from Hurricane Harvey, so flooding remains front of mind.

Flooding is not a constant problem in most of our communities, but it is a continuous one. In times between disasters (what emergency managers refer to as “blue sky”), it’s easy to fall into familiar practices and forget to prepare for future flooding.

These three workshops happened to coincide with weeks of record rainfall in central PA, but even if they hadn’t, they were intended to remind people who the risk of flooding is not going away. Whether you own a home that might be damaged, or work for an agency or local community, there are things you can do to help safeguard against the next flood, and there are people and agencies available to answer questions and provide assistance.

John Gardosik is the Hurricane Sandy Recover Project Manager at the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office. Though new to Pennsylvania, he is married to a Lancaster native and is enjoying getting to know the Commonwealth.

Last month we talked about how researching a place’s history and physical context factors into hazard planning, and what kinds of building elements are most at risk. This week’s post focuses on taking action and what can be done to protect historic places and their features. Continue reading

Picture yourself – lounging poolside, lakeside, or on the beach – with your tablet or smart phone (or even good old-fashioned paper) enjoying the hottest summer publication that hasn’t yet made the New York Times bestseller list: #preservationhappenshere, Pennsylvania’s next statewide historic preservation plan. Continue reading

Historic resources inform citizens of their unique local heritage, cultural identity, and the origins of their community. They are the corner stones of our built environment and they provide a “sense of place”. In the aftermath of a disaster, these buildings, structures, objects, and sites are often associated with the very memories and connections that a community needs to begin to rebuild. Continue reading

Are you interested in making a difference through disaster management planning? Do you want to be on the forefront of proactive historic preservation? Continue reading

© 2025 Pennsylvania Historic Preservation

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Recent Comments