On a sunny August morning in 2017, a group of Pittsburgh-based architects, historians, artists, students, preservationists and art enthusiasts convened before venturing out with a shared goal; to experience first-hand nearly all public artworks accessible in the vicinity, both indoors and outdoors, created by the late Virgil Cantini (1919-2009).

Our itinerary for this organized tour was ambitious, reflecting the artist’s prolific career, replete with large-scale works in communal settings.

Tour Stop: Cantini’s Studio

We passed a significant site – the artist’s former studio – along our route toward the University of Pittsburgh, where Cantini once studied and held a professorship in the Henry Clay Frick Department of Fine Arts before ultimately going on to initiate and lead the Department of Studio Arts for the University, still active today.

“My feeling is that art is not confined to a particular media. To me, painting, mosaic, sculpture – all are a form of a man’s expression,” Cantini once reflected.

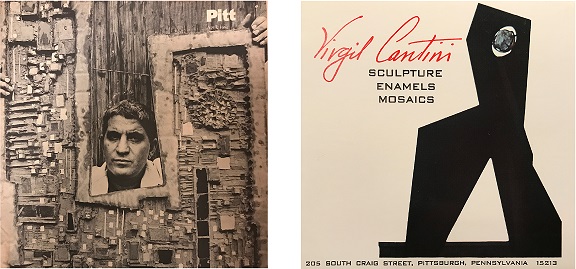

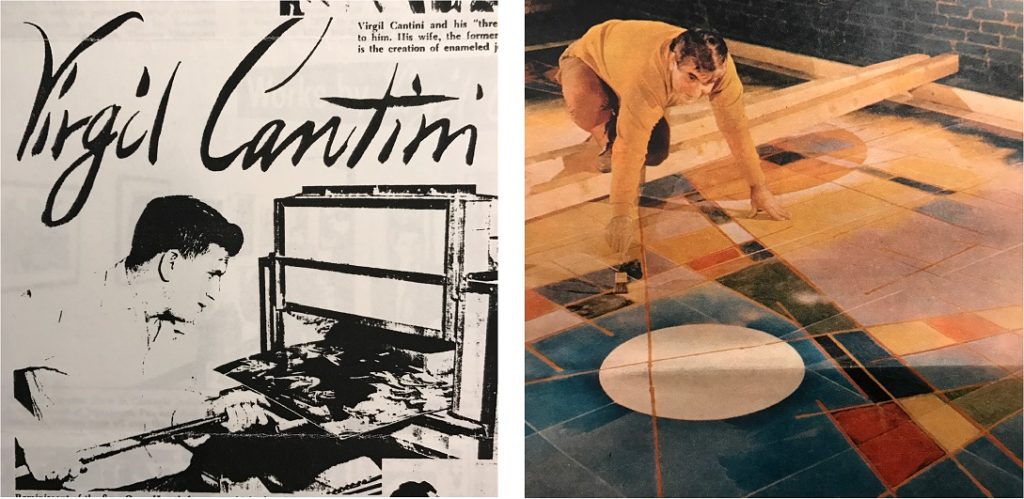

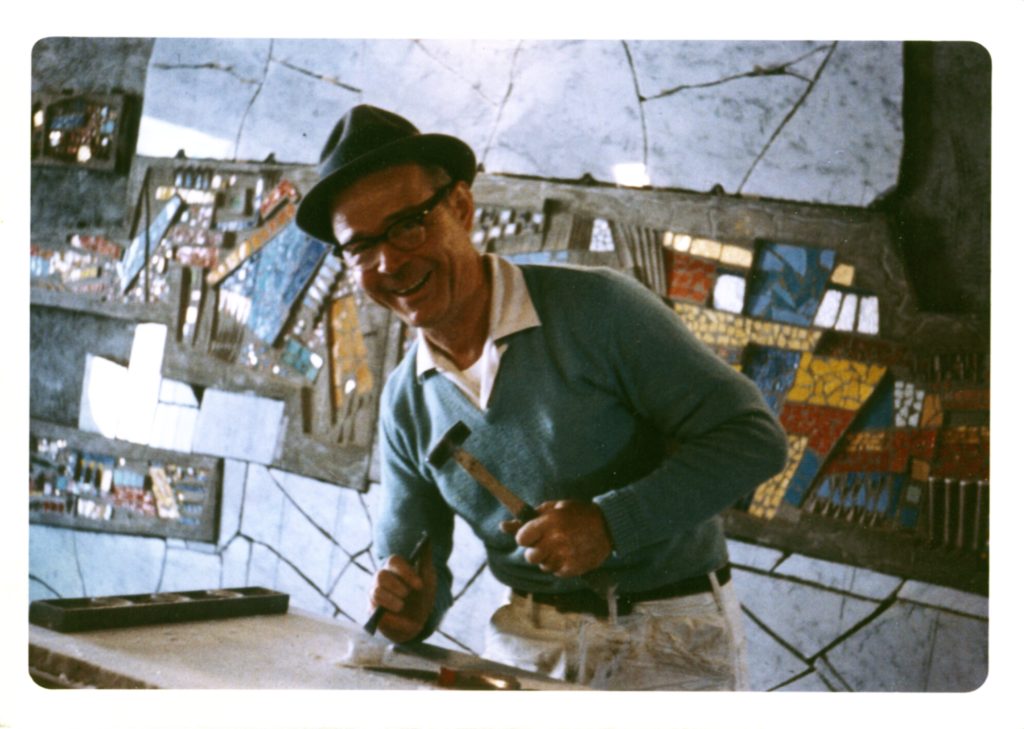

Throughout his lively, fascinating creative practice concentrated between the 1950s-1980s at his Craig Street studio address in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood, the artist – like a multi-instrumentalist – combined traditional with modern/experimental processes as he manipulated wood, metals, glass, fiber, paper, paint mediums, and enamels into sculpture, printmaking, mural installations and various compositions.

Cantini and his family arrived in the United States from central Italy in 1930, before Virgil was 10 years of age, first settling in Weirton, West Virginia, where the artist would go on to work in the local steel mill and newspaper office before emerging as a Pittsburgh denizen where he would eventually satisfy his true calling in the arts.

Following study at Manhattan College in New York, a football scholarship funded his education of the Fine Arts at Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh (now Carnegie Mellon University). In 1943, Cantini enlisted in the United States Army. As a member of the Engineers Corps, he constructed three dimensional models using aerial photographs before returning his focus to the fine arts.

Perhaps most prominently, Cantini came to be considered a master of the ancient decorative material of enamel, achieved through an elaborate process in which crushed glass of various hues is fired in a kiln, sometimes repeatedly, to achieve rich layers of the resulting opaque, smooth and high-gloss surface. Typically applied in large, vivid swaths across metal panels, Cantini also utilized enamel pieces as small mosaic tesserae.

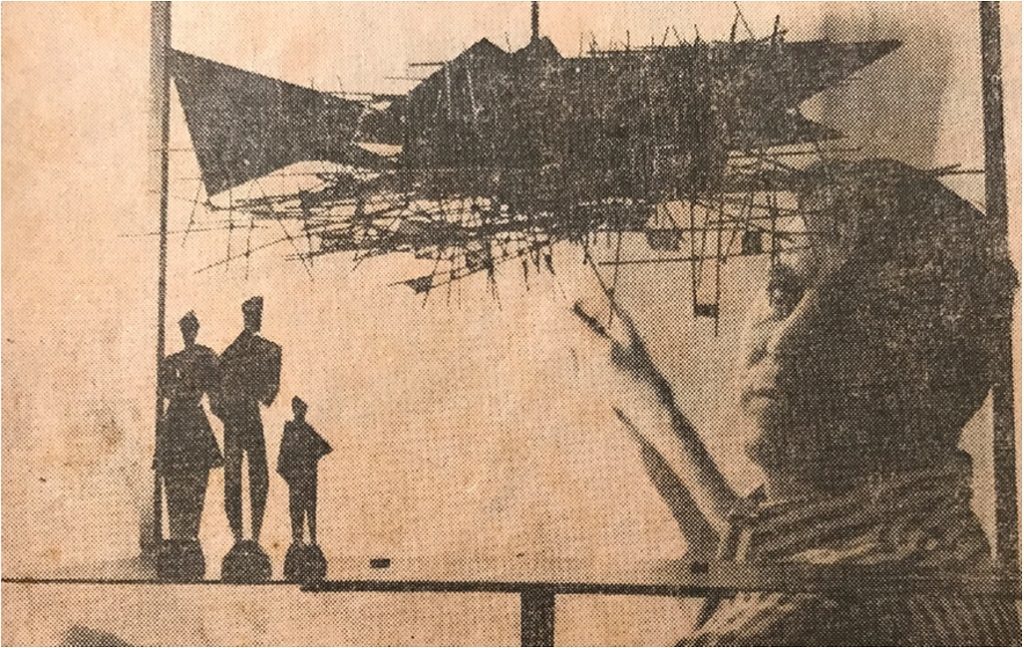

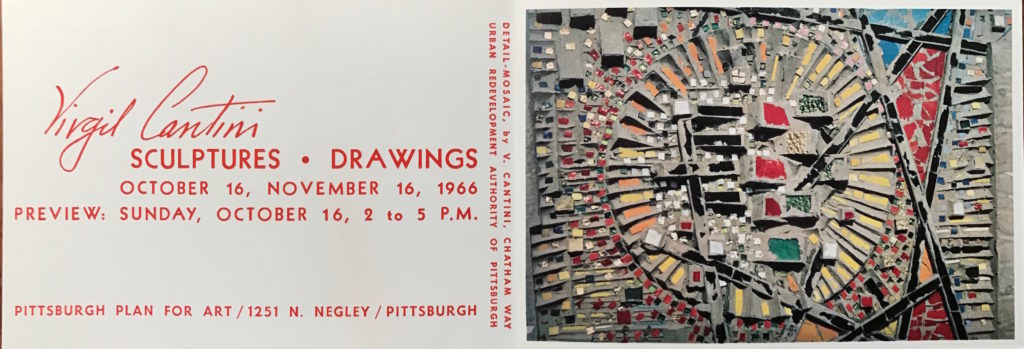

While much of Cantini’s early artistic production consisted of small-scale pieces, studio experiments, and occasionally special objects and stained glass for places of worship – by the 1960s, his practice had blossomed toward significant commissions resulting in substantial public works. A range of universities, architectural and landscape designers, City divisions, and patrons were eager to engage this sought-after, multi-media artist in noteworthy projects, reflective of the ongoing mid-20th century trend (and in some cases, mandated ordinance) to integrate art into newly designed spaces and sites. Cantini readily participated, creating compelling visual scenarios that brought to the region lasting vitality, texture and character.

Tour Stop: University of Pittsburgh

Our August tour weaved through the University of Pittsburgh’s campus, which houses an unrivaled collection of Virgil Cantini’s public artworks, primarily modernist enamel compositions completed between 1969-1977.

While Enlightenment and Joy (1977), Science in Service to Mankind (1973),and Universal Order (1975), hanging in Posvar Hall, Chevron Science Center and the Barco Law Building respectively, remarkably remain in their original state as installed by the artist, Aerial Scape (1970) had a different journey.

An enamel mural commissioned in 1969 by Michael Rea, the great-grandson of steel magnate Henry W. Oliver, Aerial Scape was removed from the modernist lobby of the K&L Gates building (210 Sixth Avenue, formerly One Oliver Plaza) upon 2009 renovations of the 1968 property originally designed by William Lescaze & Associates.

The mural, comprised of 50 individual panels, was reinstalled in the much more confined Salk Hall Atrium (2015 addition) at the University of Pittsburgh after much delay and deliberation. With access limited exclusively to students using the building, Aerial Scape ceased to enjoy the visibility it once had in a glass-enclosed, light-filled central downtown lobby.

Modern works of public art have become increasingly vulnerable amongst cultural resources. Intrinsic to our built heritage, public art, in its many forms, necessitates and merits the same professional preservation and conservation vanguard as that which is assigned to important structures and designed sites, especially when the art is integral to the structure or site.

In a physical and discernable regard, hazards can include environmental and elemental factors taking their toll upon outdoor and high-traffic-setting works, while interior installations may further fall victim to extensive renovations including changes in surface materials. Less conspicuous threats, yet no less critical to the artwork, include alterations in presentation that may compromise the artist’s original concept or intent and of paramount importance – the viewer experience.

We continued on, passing by Cantini’s Man (1965) and Ode to Space (1966), sculptural works achieved in metal, both intact in their original locations – the first displayed upon a façade facing a major intersection, and the latter positioned on the plaza of a lecture hall in honor of former Chancellor Litchfield, and noticed by plenty of passersby.

Cantini’s interior suspended sculpture, Skyscape (1965), was commissioned by the Joseph Horne Co. department store in 1964-65 and just a little over 10 years later, the iron, colored glass, bronze, copper and steel sculpture hovering over the escalators, against the white ceiling and enjoyed from various vantage points, was removed during renovations and relocated to Posvar Hall at the University of Pittsburgh.

A 1978 interior in the late-modern brutalist style continuing to undergo contemporary renovations, the new environment offers little of the natural light and dynamic viewing perspectives of the original setting, elements which enhanced the work and fulfilled Cantini’s intended vision.

Tour Stop: Mosaic Tunnel

Our last stop on the tour was aptly arranged, feeling like an amalgam and culmination of all we had experienced and observed thus far, and would turn out to present the most urgent lesson and need in preservation along the route.

Disembarking our bus in Downtown Pittsburgh, we crossed the street toward a wide, paved walkway sloping downward, below street grade.

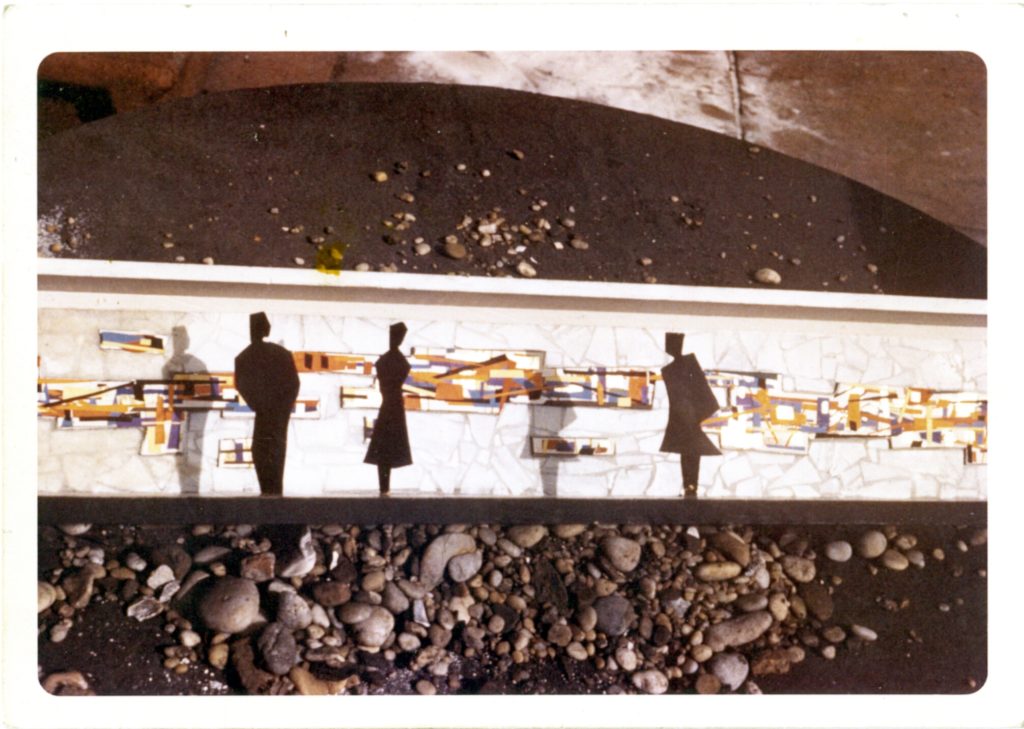

The surprising glimmer of brightly colored pieces of glass and opaque enamel dancing along the walls of a pedestrian tunnel drew the inquisitive group closer – revealing two abstract compositions along the left and right side.

Quotations from Virgil Cantini were shared as we traversed the tunnel together:

“You see, I want the tunnel to be a gallery, some place to go through rather than stay out from. It is not designed to stop you… it is meant to be something you look at while you are walking along.”

Cantini’s Mosaic Tunnel, as it came to be called, was conceptualized and completed by the artist in 1963-64, the outcome of a commission from the Urban Redevelopment Authority for an artwork to be integrated within a 60-foot long pedestrian tunnel in downtown Pittsburgh.

Remaining intact through until April 2019, 55 years after its creation, Cantini’s immersive installation presented an exceptional arrangement of mosaic compositions, purposefully irregular and embedded into a heavy mixture of concrete which the artist integrated by creating texture and linework directly into the custom aggregate.

Cantini’s installation consists of 28 individual panels that were composed and crafted at his studio on South Craig Street in preparation for on-site installation. Intended to be experienced by the everyday passerby, the completed overall work delivers the effect of two horizontal ribbons stretching along the tunnel walls.

One length of the composition evokes an abstracted cityscape, the other, an aerial perspective of urban topography, all rendered in bold geometric forms and with metallic accents. The individual panels, some up to 6 feet in length, are installed in a slightly askew linear composition, with planned space between. The colorful mosaic sections are surrounded by large irregular pieces of white marble, and a ceiling of standard white square tile, as installed under Cantini’s direction.

“By spacing the mosaics, I hoped to create the idea of a strata cut into the earth – the city growing out of the earth and not bound by a frame. You visualize the city simultaneously from many points of view”

Originally located beneath Bigelow Boulevard, connecting Chatham Street to Seventh Avenue, this public artwork came about when Robert Pease, then Executive Director of the Urban Redevelopment Authority invited Cantini to imagine a work as a public amenity to connect neighborhoods and allow pedestrians to bypass busy roadways, as part of the Authority’s overall improvement of the area during the period, in the wake of urban renewal.

Pease, inspired by the vibrant mosaics he experienced in subways and public spaces during a tour throughout Europe, found a fitting visionary in Cantini to create an absolutely distinct experience for the citizens of Pittsburgh. The project was funded by the federal government, supporting the mission that public art be integrated whenever and wherever possible.

“The art is supposed to lend a feeling of movement, not of a specific image. I want to give an experience of sensing the city – both day and night… gold and silver will shimmer like the lights of the city.”

Cantini’s distinctive mosaic exemplifies the artist’s desire for his work to be encountered freely in the public realm and his ability to execute a dynamic composition in such a context. Experiencing the work in-situ and in its entirety has conceptual and sensory value intended by the artist. As one briskly passes through the polychromatic corridor, the linear arrangement moves you through, while glistening metallic enamel pieces occasionally catch the eye, much like the city lights Cantini intended to celebrate.

Recognizing a Landmark

Months earlier, as I was preparing the tour itinerary and reaching all those affiliated with Virgil Cantini to enhance my related research, I met his daughter, Lisa Cantini-Seguin and enjoyed what would become an important exchange, later unfolding to redirect the fate of her late father’s most exceptional achievement in public art in Pittsburgh.

Having been informed by city officials during 2016 that a new park design, coined the I-579 Cap Project, would require infill of the below-grade tunnel area, and therefore the 1963-64 mosaic installation – Lisa was offered a fractional number of the panels, pending they could be efficiently removed.

Sensing that this was an inadequate resolution and underestimation of the artwork’s worth, but unsure how to navigate the logistics, Lisa soon found a platform and network of professionals to support her vision to reach a suitable outcome for the unique mosaic.

This installation demonstrates Cantini’s artistic vision, technical skill and engagement with the current trends of public art during his practice. A discernable genre of modernist mosaics was being established, and Cantini’s mosaic work embodies distinctive characteristics of the genre.

Contemporaries of Virgil Cantini’s, such as Hans Hoffman, Jeanne Reynal, Max Spivak, and Lee Krasner, had created modern mosaics in public spaces, upon and within structures, during the 1950s-1960s. Expanding upon the ancient artistic medium of mosaic, traditionally depicting human figures, historic scenes and landscapes, modern artists adapted and experimented with the medium, arranging tesserae to create abstract compositions, modern interpretations of landscape, or bold explorations of color in their own stylistic language.

The qualities of Cantini’s mosaic certainly can compare, making it a distinctive and excellent contribution to this important aspect of modern art history and artistic practice.

Cantini’s Mosaic Tunnel is his only public mosaic in the Pittsburgh area and the only one of its kind, in scale and site-specificity, in Cantini’s body of work. The very experience of traversing the subterranean tunnel offered an overall vignette of the City – of its rhythms and patterns, by day and by night – all below ground.

It could not be lost, we all agreed. A casual reception following our tour quickly took the form of an impassioned session to strategize preservation possibilities.

There is a noteworthy difference between a movable sculpture or panel composition that happens to be anchored to a plaza or affixed on a wall, and an artwork which envelopes the site and encompasses the viewer. The latter, as in the example of the Mosaic Tunnel, is distinctly influenced by and physically related to its site/structure on a more complex level – requiring particularly important considerations when it comes to relocation, preservation and restoration.

Part 2: Saving Cantini’s Mosaics

Next week, in part-two of this article, learn how a complex Section 106 process unfolded, ultimately resulting in the safeguarding of this historic cultural asset and a collective reclaiming of Cantini’s mosaic as a comprehensive modern work of art.

Ahead we have the collaborative task of translating the characteristics Cantini crafted to an entirely new setting – ensuring that the artist’s purpose in public art is experienced in the future.

Today’s guest contributor is Brittany Reilly. Chair of the organization’s Modern Committee, Brittany joined Preservation Pittsburgh’s Board of Directors in 2017 with particular interest in mid-20th-century modern and postmodern architecture and design of Pittsburgh and the region. As Executive Director of the Irving and Aaronel deRoy Gruber Foundation, she manages a collection of artwork by the late, Pittsburgh-based artist Aaronel deRoy Gruber (1918-2011), and curates the Foundation’s gallery space in the historic Ice House Studios in Lawrenceville. She is perpetually exploring modernist material culture, public art and craftsmanship at their intersections. Brittany received her M.A. in Visual Arts Administration from New York University, Steinhardt (2013) and B.A. in Visual and Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2005), focusing on non-profit management combined with art, architecture, and design history.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

I am so glad the mosaics were saved. I greatly appreciate the time and efforts of those who prevented their destruction.

I hope that a new location for the mosaics

will be found soon

Works such as the Cantini Mosaics enrich urban areas. Outdoor sculptures and artworks lend an air of sophistication and joy to cities.

I have a piece of art by Virgil Cantini and am wondering about it’s worth. I believe it is called the Tent of Divine Presence that was commissioned by a Catholic church we think, in Youngstown. It is rather large, three pieces, 38″ x 26″ each, enamel on metal. The colors are beautiful. Could you give me any information about it? I can send pictures is you like. I’m not sure how to do this on this page. Thanks