Did you know that Pittsburg’s H.J. Heinz was one progressive dude!?

First, some context…

A few weeks ago, we introduced you to the exciting new data management system, PA-SHARE, that will be up and running in a few years. As we transition from paper files to digital files, one of the biggest – and most important – steps is to scan our extensive archive. This has uncovered some really cool stories!

The Heinz factory (PA SHPO key #005607) in Pittsburgh is one them. The extensive property in Pittsburgh’s Strip District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in July 2002. In 2005, it was rehabilitated into the Heinz Lofts using the federal historic tax credit program.

Now the fun stuff…

At the turn of the century Pittsburgh was a booming industrial city. Residents such as Andrew Carnegie, George Westinghouse, Henry Frick and of course, H.J. Heinz began to make their mark on the “Iron City”.

Henry J. Heinz in 1917.

During the 19th century, Pittsburgh found itself engulfed in the success of manufacturing and industry. This shift from working at home to working in factories brought with it a new system of working and new work force. Many factory and mine owners sought to control and discipline their workforce by enforcing long working hours, providing low wages, and disregarding hazardous working conditions for employees. And you thought your job was bad!

Even though employers were generating great personal wealth from business growth, their workers received low pay and few benefits. The situation was worse for women and children, as they often received only a fraction of the wages a man could earn.

During the summer of 1877, after the railroad companies cut railroad workers wages for the third time in a year, workers banded together and went on strike. Known as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, railroad workers demanded increased wages and better working conditions. All railroad trains halted movement until the conditions were met. The strike lasted forty-five days, but the implications lasted longer.

What does the Great Railroad Strike have to do with ketchup?

The strike prompted many employers to reconsider common manufacturing practices and employee conditions of the era.

After the 1877 Strike, along with several other industrial strikes across the nation, the federal government became involved in the “Industrial Betterment Movement”. Early campaigns encouraged employers to improve and provide safe working conditions for employees, hoping that if employers invested in employees, the incentive for people to strike so quickly would dissolve.

This resulted in increased profits for employers and safer working conditions for workers. Which basically means, everyone can make a lot of money if we treat everyone fairly.

Enter Pittsburgh’s Henry Heinz…

The son of German immigrants, Henry J. Heinz started selling condiments in the early 1860s. After early success with products like sauerkraut and horseradish, Heinz founded the Anchor Pickle and Vinegar company in 1869 but ended up bankrupt by 1875.

In 1876, Henry Heinz was ready to make some big money. He partnered with his brother and cousin as the F. and J. Heinz Co. and first introduced their famous red tomato-based sauce called catsup.

A little FYI here… catsup and ketchup are really the same thing, just spelled differently. Dating back to 17th century China, ketchup was originally a paste made from fermented fish guts, mushrooms, walnuts, or shellfish. Ketchup as we know it today didn’t come about until the mid-19th century.

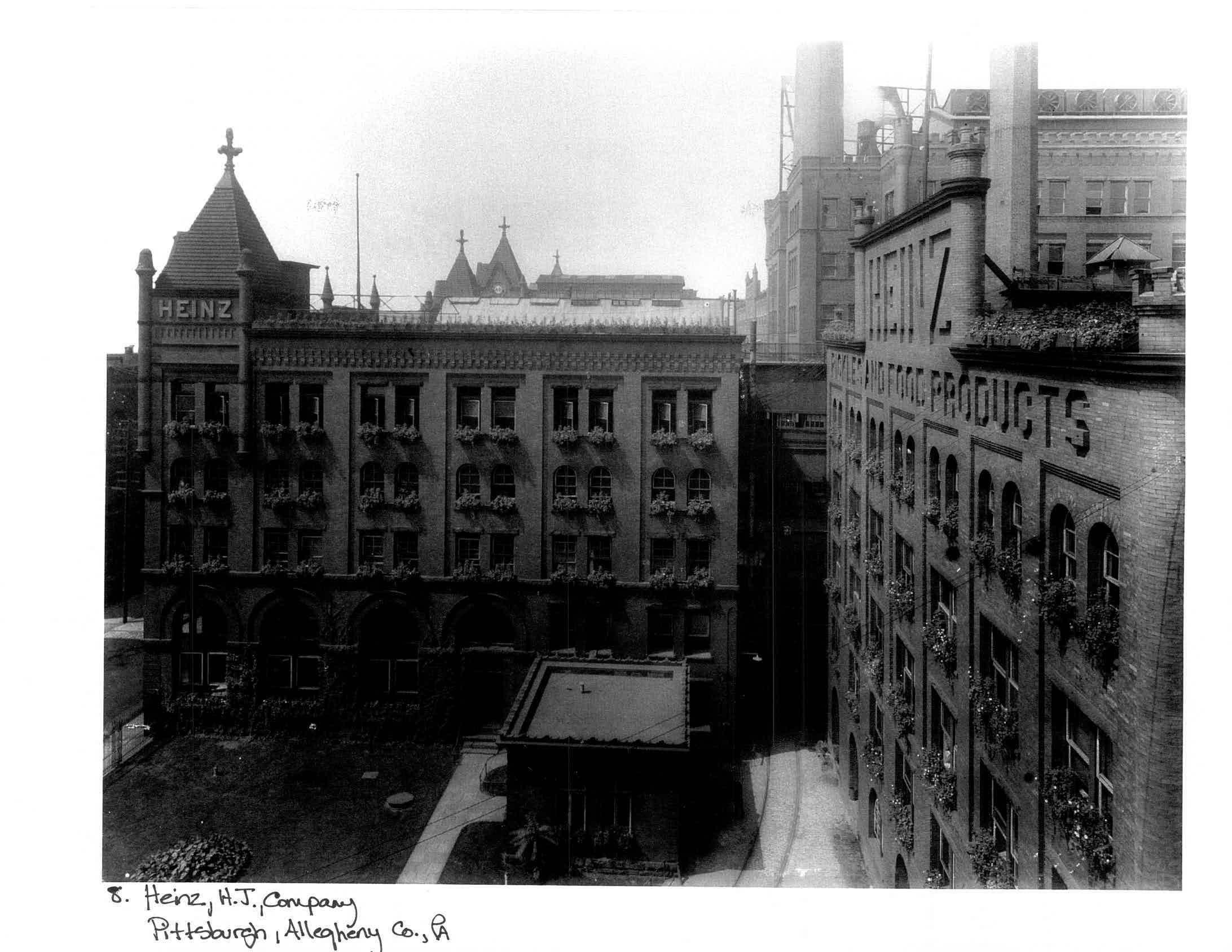

By 1888, the company was successful enough that Heinz bought out his family and created a new company to package and sell his famous Tomato Ketchup, the H.J. Heinz Company. At the same time, the company started an impressive construction campaign with seventeen Romanesque Revival buildings.

H.J. Heinz Company, Pittsburgh, PA. Postcard from the PA State Archives.

Heinz became focused on creating a healthy and safe work environment for his employees, while still creating a manufacturing facility and a marketable business. Heinz did not want his company to fall victim to strikes or bad publicity, he wanted to create a strong company with loyal employees and give his delicious sauce to every french fry lover in the world. #Goals!

The architecture of the H.J. Heinz Company’s building and factory grounds demonstrate the balance he sought between worker welfare, and his need for a modern manufacturing facility. Heinz and the architects Albert Kahn and Robert Trimble, incorporated functional design with aesthetic elements, creating a model industrial complex.

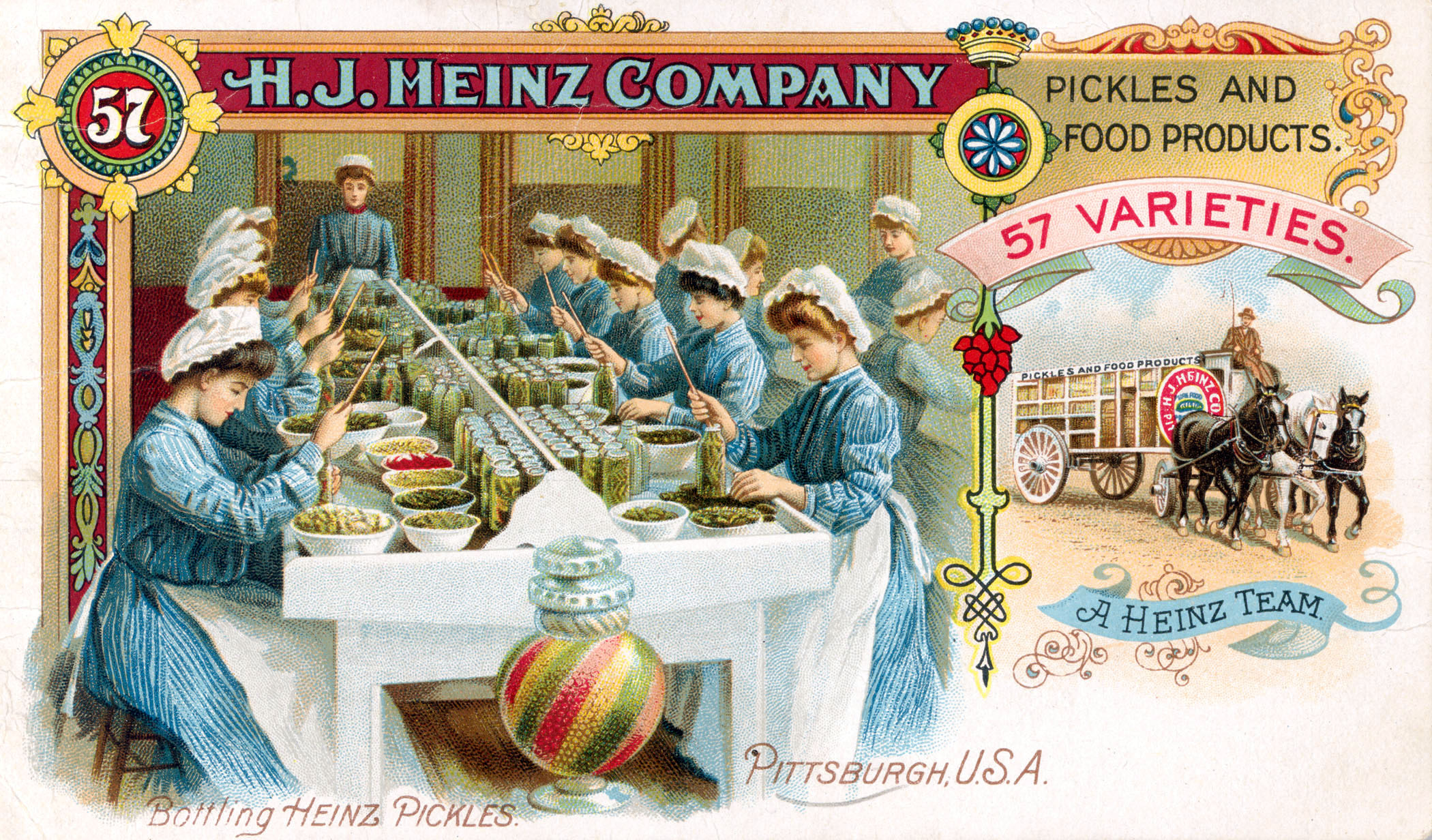

Bottling Heinz Pickles. Postcard from the PA State Archives.

With design elements such as large windows, skylights, and monitors, Heinz provided a great deal of natural light, allowing the workers to see what they were doing. This light and air provided a less dreary environment for employees. The light and space also allowed room for greenhouses and gardens throughout the facility and on the roof tops. Crazy to think that just providing windows for people was a big deal, but it was!

Gardens at the H.J. Heinz Company. From the Heinz Company National Register Nomination, 2002.

Roof top gardens. From the Heinz Company National Register Nomination, 2002.

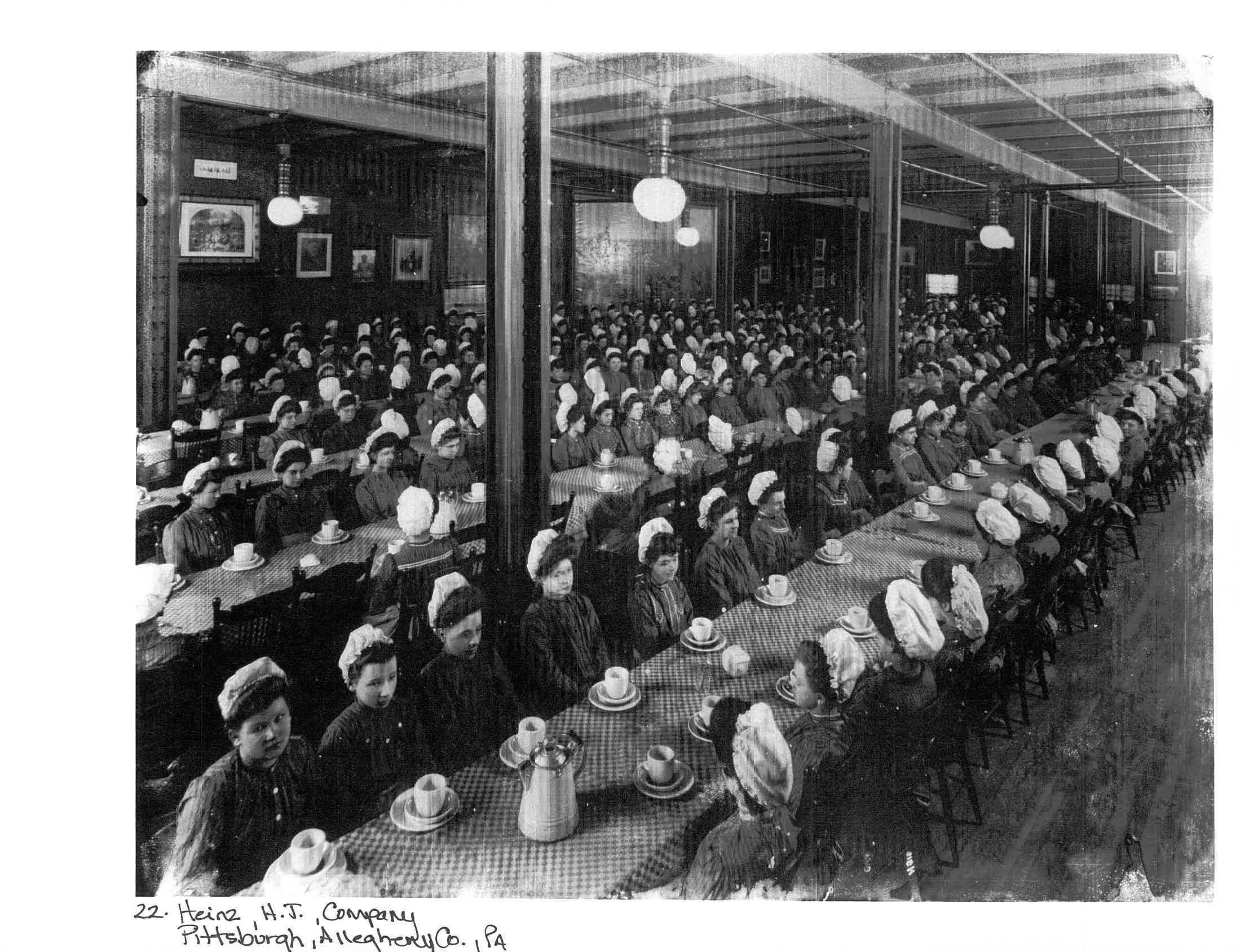

With the company’s expansion to seventeen buildings also came room for a gymnasium, meeting rooms, large lunch rooms, and an indoor swimming pool. The factory design also incorporated bath houses, locker rooms and adequate staircases. These new spaces addressed the workers’ physical welfare and helped to prevent work injuries by encouraging workers to stay fit. For the first time in manufacturing history, employees were able to have access to a range of amenities within their workplace.

Ladies in Lunch Room. From the Heinz Company National Register Nomination, 2002.

The H.J. Heinz plant also had hot and cold running water, dressing rooms, marble wash basins, showers and reclining chairs, all of which could be utilized after working hours, at no cost. Hot AND Cold water!? This may seem like a basic perk at your job now, but this was wild for the time!

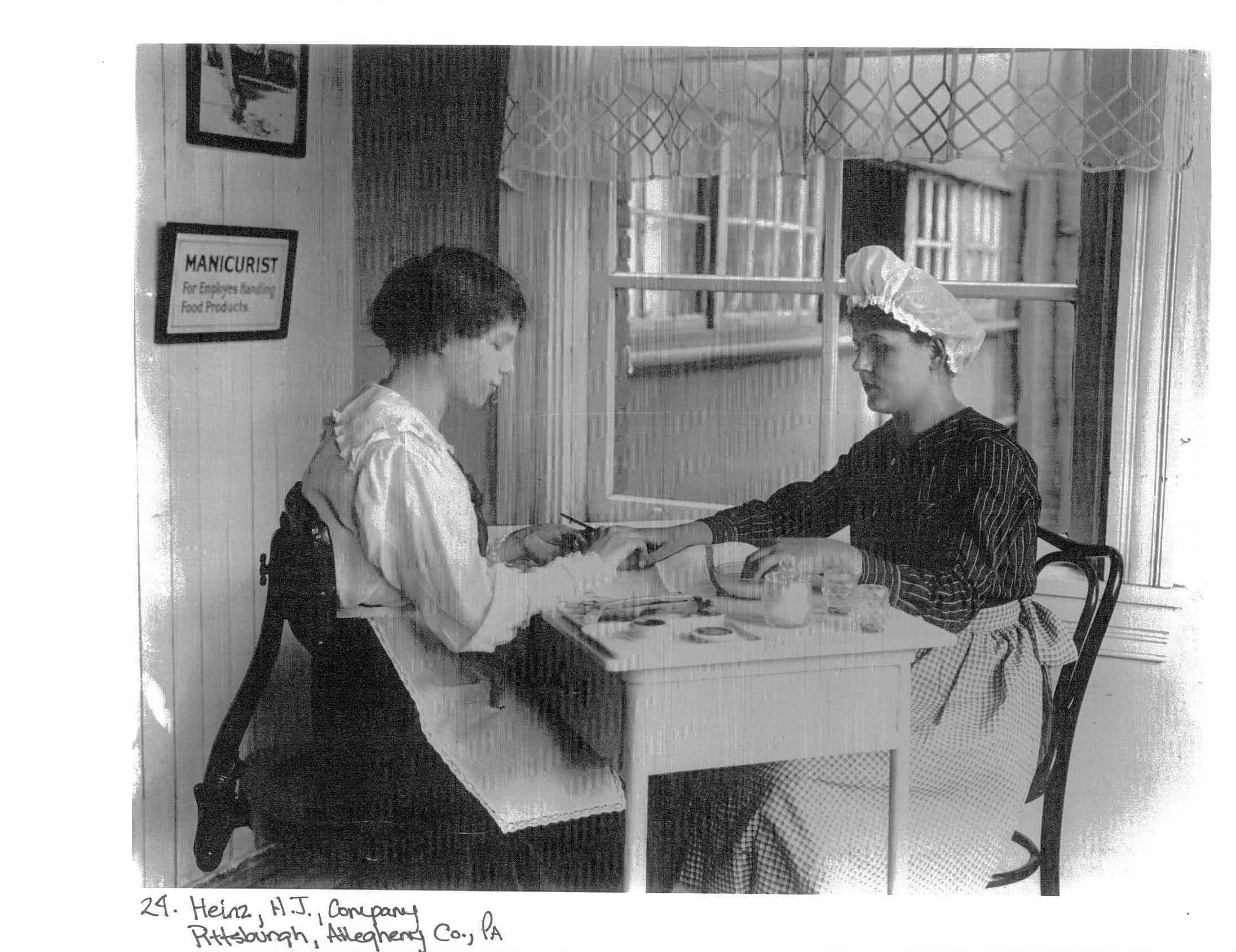

Heinz also provided a nurse, physician, and two dentists. Food handlers even received a weekly manicure!

Food handler with manicurist. From the Heinz Company National Register Nomination, 2002.

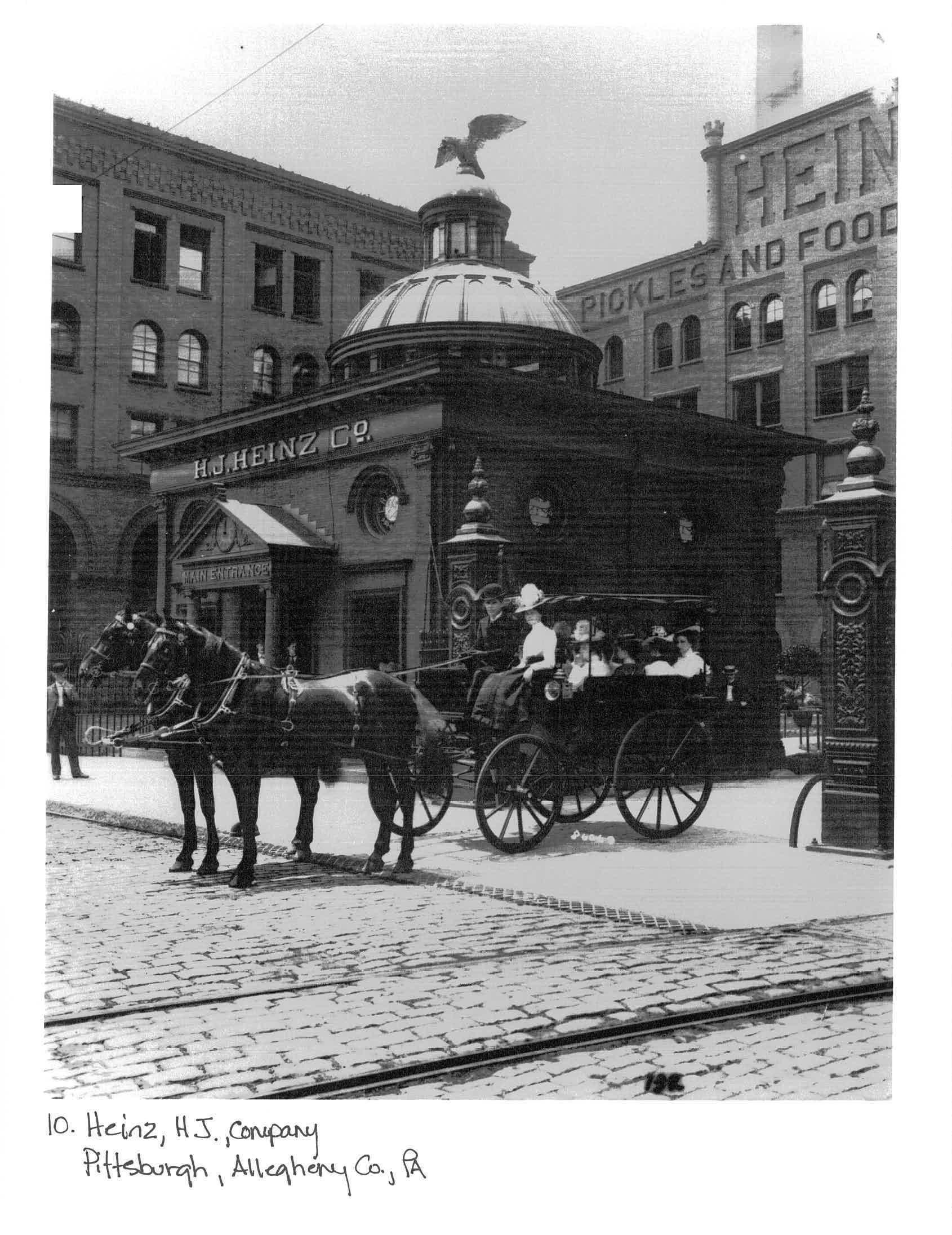

In the summer, ladies could go for a horse-drawn carriage ride through the park and observe the factory gardens. These revolutionary concepts created a new atmosphere and mindset for employees and Pittsburgh residents.

Carriage ride. From the Heinz Company National Register Nomination, 2002.

Heinz was not only placing value on his factory, but also the people within it. Heinz’s ability to create a safe environment for his employees while still being able to establish a successful business, helped to alter the manufacturing methods throughout the United States.

His progressive methodology and investment in his employees spurred local and global loyalty to the company for over a century and is effective still today. The company even gives its employees off for Super Bowl Monday! Talk about being progressive!

Today’s post is by Susan Landis from JMT. Susan is the project lead contractor for the State Historic Preservation Office Digitization Project. She has been contracting sporadically with the PHMC for numerous projects since 2013. Her specialties include Historic Preservation and Archaeology.

Very good story and interesting to hear of such a progressive employer.