There’s a scene in the 1960 classic, The Time Machine, where Rod Taylor escapes the imminent nuclear war by throwing his machine fast into the future. Quickly, the ground rises all around him and for what appears to be an eternity, he is sitting there isolated from the outside world. At that moment, as we watch him shivering, we wonder with him what is going on above ground. An archaeologist would empathize with Rod Taylor at that moment, not because he has put himself into a tight spot, but because Taylor’s experience is the experience of all artifacts in the ground. They are part of the world, then they are no longer part of the world, having disappeared beneath the earth.

As we live and walk on the earth today, we are equally oblivious of what there is lying beneath us. Ten years ago trucks and cars motored on Dyott Street in the industrial Kensington-Richmond section of Philadelphia. The Kawa Trading Company warehouse is just to the east. Several hundred yards east of that is the Delaware River. The closest glassware and dinnerware store is in Center City, miles away. Yet a few feet under Dyott Street, cut off from the world for 125 years, sits the remains of the Dyottville Glass Works, along with discarded bottles, perfume vials, flasks, pitchers, toys and diverse glass objects. There and elsewhere in the area, along I-95, at Aramingo, in Fishtown, Northern Liberties, and Port Richmond, artifacts from just below the pavement are making their reappearance at the Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center in an exhibit titled “From the Ground Up: archaeology, artisans, everyday life.” The exhibit runs from April 1 through December 31, 2016.

www.diggingi95.com

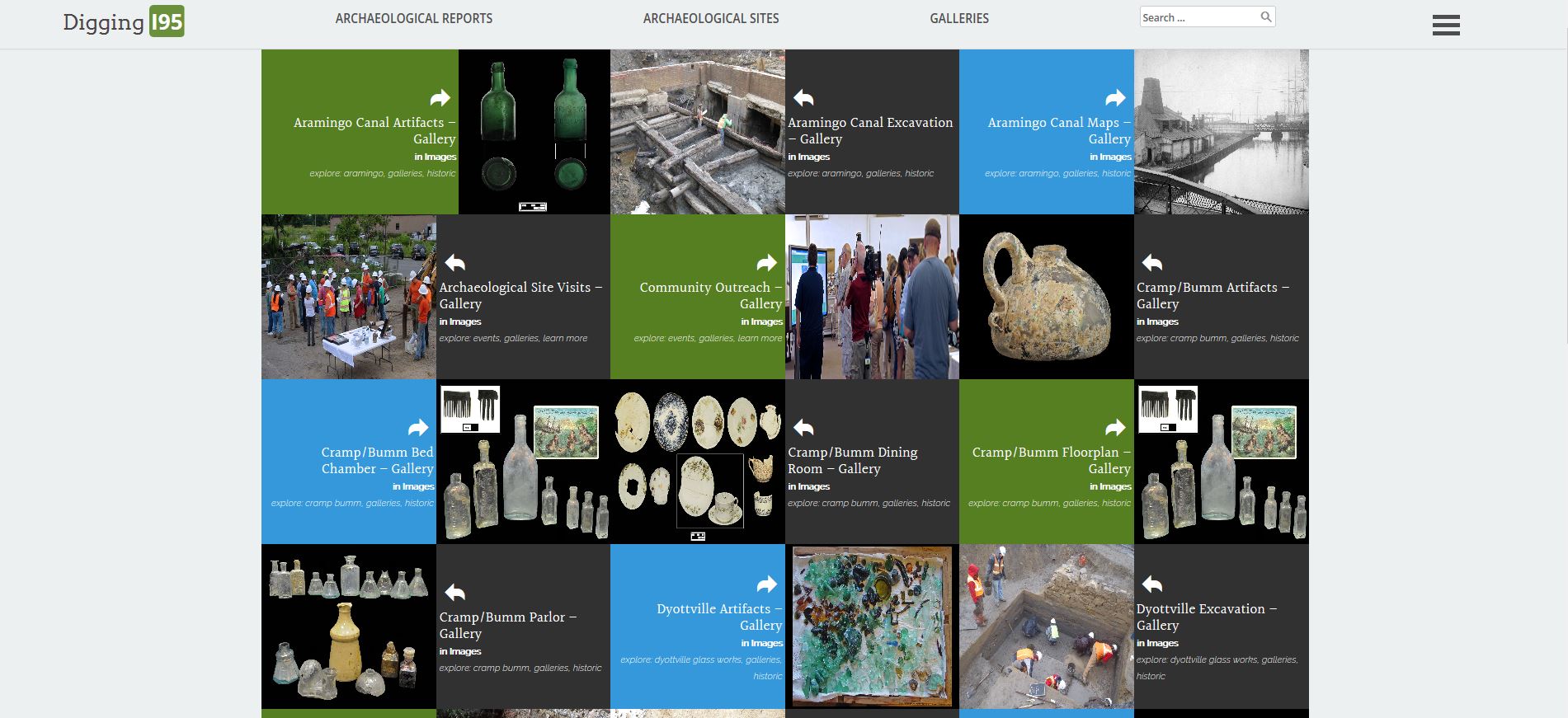

The story of the I-95 excavations, and much more, can be found at www.diggingi95.com and this short piece gives you a great synopsis of the technology behind this amazing website.

Map of the I-95 investigations from the interactive digital report www.diggingi95.com.

How does something so lost and abandoned find its way into a major exhibit at one of the nation’s premier glass museums? The impossibly correct answer is PennDOT. Yep, the same people who bring you asphalt roads, concrete and steel bridges, plow the major roads in winter, fix them in the spring, also dabble in the archaeology business. More precisely, PennDOT follows a slew of environmental laws passed in the 1960’s and 1970’s, one of which is the National Historic Preservation Act (which turns 50 this year!). One of the Act’s provisions, Section 106, requires that an agency receiving Federal Funds consider the impacts its projects have on historic resources, including archaeological sites. Because of Section 106 and because PennDOT and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) were undertaking a major reconstruction of I-95 between the I-676 and Allegheny Avenue Interchanges, PennDOT with the assistance of AECOM (formerly URS Corporation) archaeologists and with support from Hardlines Design Group undertook studies where it thought important historic and prehistoric sites might be found.

Excavations along I-95 in Philadelphia.

Archaeology under Section 106 is normally an exploration that leads to further investigation, depending on what is uncovered. Phase I is usually identifying what archaeological sites are present in any project area. Phase II investigates these sites to determine whether they are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. Phase III is typically data recovery excavations of the site for important information. Work is phased in this manner largely due to the high cost of fieldwork, and the importance of bringing all stakeholders to the table at critical points.

Archaeology in urban settings, such as this project required a different approach. In cities especially, Phase I identification testing is logistically difficult, expensive, and often disruptive to residents. Phase I urban archaeology begins with extensive historic background research and especially historic map research to figure out what might be buried underground, sometimes under 10-20 feet of modern fill. Archaeologists then use heavy equipment to carefully strip away the modern layers to hopefully expose what the historic maps suggest. In this sense Phase I and II are conducted concurrently; the archaeologist having to find artifacts and features, and instantly understanding their importance.

Uncovered artifacts in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood.

With regard to Native American archaeological sites, the likelihood of encountering any preserved archaeological sites has long been thought to be rare or impossible. The number and material preservation of the pre-contact sites identified in this project suggests these assumptions are wrong and that preserved sites may be much more common deeply buried under Philadelphia and other major cities. We are only now developing a theory of how and where pre-contact sites may be found under large urban areas. The number and condition of pre-contact sites identified in this project was truly a surprise.

Work began on different sites at different times beginning in 2007 and finishing by 2014 (fieldwork for the entire GIR section is ongoing but not covered by the exhibit), but the significance of these sites was realized within days and sometimes hours of the exposure of the relevant deposits. For historic archaeological sites, confirmation of what you suspect from the background research can come very quickly. The remainder of fieldwork is usually to document the size, extent, and complexity of the resource. And in the case of the Hope Farm/Richmond Hall Site, additional work uncovered the pre-contact site that underlain the historic site.

Local pottery finds from area industries.

Nearly 1,000,000 artifacts from 5,000 years of history were recovered. Notable sites included:

- Aramingo Canal – a 19th century canal and local industries

- Fishtown One and Two – multiple 19th to early 20th century residential and prehistoric archaeological sites.

- Hope Farm/Richmond Hall– a prehistoric archaeological site on the grounds of an early historic period estate

- Dyottville Glass Works – a 19th century glass factory

- 10 prehistoric sites yielding 45,000 artifacts along the Delaware River Waterfront in Kensington. These sites have been dated to between 3560 B.C. and 1500 A.D.

- Gunner’s Run South – multiple 18th to 20th century residential sites containing military artifacts possibly associated with the British occupation of Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War, and a Native American archaeological site,

The 600 artifacts that will be showcased in the Wheaton exhibit are from archaeological sites that have had their excavations completed and will not be impacting the construction work or schedule. Work is ongoing insofar as this is a very large and complex project that requires it to be staged.

Wheaton’s display of Native American artifacts.

The exhibit at the Museum of American Glass at WheatonArts represents the pinnacle of public outreach undertaken by AECOM and District 6-0 (through Catherine Spohn, District archaeologist). For the last 3 years, they have campaigned to highlight the findings from this project and to bring the knowledge and artifacts to the general public and especially to the local communities that are being affected by the project’s construction. To date, nearly 80 individual public outreach programs and events have been completed to highlight the I-95/GIR project and the archaeological findings resulting from it. Individual outreach efforts included site tours of active excavations, illustrated presentations to a wide assortment of professional archaeological and community organizations, long-term museum exhibits, one day “pop-up” artifact displays conducted in partnership with community institutions (churches, schools), and contributions to numerous television and print media stories.

What makes the Wheaton exhibit special is how exceedingly rare it is for a Section 106 archaeology project to provide artifacts and information that is of national interest. The jewel of the collections being displayed at Wheaton is the Dyottville Glassworks artifacts, and it is no coincidence that the overall exhibit covering the range of material culture found under Philadelphia ended up at an institution primarily known for its Museum of American Glass. The range of artifacts found at Dyottville and in the glassworkers’ neighborhood, documenting the manufacturing process, the variety of objects produced, and even the idiosyncrasies of the individual glassblowers, is unique in the US. Among glass historians, this collection is creating a real buzz.

Installation of the amazing glass display at Wheaton.

To understand how rare this is, realize that for PennDOT’s entire program, staff archaeologists lead the equivalent of 2 data recovery excavations a year. Most of these end up as reports, maybe a local display or talk, then the artifacts are boxed up and sent to Harrisburg for curation. We generally don’t get “big finds.” I-95 is a once-in-a-generation result; and the work isn’t even finished. From the manufacturing history of Philadelphia, to the surprising preservation of indigenous archaeological sites in the city, to the detailing of the history of Philadelphia outside Center City, this project is groundbreaking, literally and figuratively.

The Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center is located at 1000 Village Drive, in Millville, New Jersey. It is open Tuesday through Sunday 10 AM – 5 PM. General admission is $10.00 for Adults; $9.00 for Seniors; and, $7.00 for Students. Children 5 and under are free.

This post for Archaeology Month was shared with us by Ira Beckerman, Ph.D., RPA who serves as the Cultural Resources Unit Chief in the Environmental Policy and Development Section of PennDOT’s Bureau of Project Delivery.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

Leave a Reply