To say that COVID-19 changed things about away we live our lives would be the understatement of the century. Virtually everything about the ways in which we live, work, learn, recreate, shop – everything – changed in an instant and we have spent the last 12+ months learning how to adapt, as individuals and communities. The pandemic has also prompted a lot of pondering and forecasting about the long term effects on our society and how many of these adaptations will become part of our “normal” lives going forward. In Pennsylvania’s traditional communities, the sudden loss of foot traffic, festivals, and events hit small businesses and restaurants especially hard. Revitalization organizations and local governments have had to reimagine, with little or no time or experience, how to allow people to use streets, sidewalks, parks, and trails in a safe and responsible manner. Enter Designing for Distance.

For almost a year prior to March 2020, the PA SHPO and the Pennsylvania Downtown Center (PDC) had been working to develop guidance for design guidelines in historic communities with support from a Certified Local Government grant. When COVID hit, work on that project paused and our priorities shifted to response and support for the Commonwealth’s struggling communities. By mid-summer it became clear that the public realm – the spaces outside the doors of the businesses and restaurants – had taken on a newly important role as space where people could gather and business could happen, but only in a controlled manner. This was reinforced by the work of PDC’s Resiliency Task Force the Ready for Preservation webinar that PDC and PA SHPO co-sponsored in May 2021. PDC and PA SHPO decided to pause the design guidelines project and redirect the grant funds to pilot projects that provided design-based solutions to the need for social distancing and increased utilization of outdoor spaces.

The first stage of the Designing for Distance was selecting the communities to participate in the program. PDC put out the call to their network of local revitalization partners and asked interested communities to submit a statement of interest identifying a need/challenge their community was facing related to COVID that might be addressed with a design-based solution. Four communities of different sizes and locations were selected – Easton, Erie, Lewisburg, and Reading. Each of the four communities also had a distinct need and a unique problem that needed some attention, which allowed us to explore a range of solutions. For Julie Fitzpatrick, Executive Director of PDC “these communities represented a variety of different types of public spaces and configurations that could be relatable and applicable to other communities throughout the Commonwealth.”

The second step was to select the design teams. PDC issued a Request for Qualifications to architects, planners, landscape architects, engineers, and other design professionals throughout the Mid-Atlantic and invited firms/teams to express their interest in working on one or more of the pilot communities. A committee of PA SHPO and PDC staff then reviewed the applications and consulted with the community partners to select the right team with the right approach and experience for each unique problem. PDC then contracted with the firms to provide a scope of services for each community and provided them with a stipend for their time and effort.

Working on a short timeline – only 2 months – the design firms spent time understanding the needs of each community, developing possible solutions, and soliciting feedback from the community partners. Because each project was unique, the process and products were all a bit different as well, but have already proven beneficial for the subject communities and provide useful guidance to other places. From Julie Fitzpatrick’s perspective, “over the last few months, the firms have developed outstanding conceptual plans to identify each community’s individual focus and needs. We anticipate that life will be different for the indefinite future, and we believe these projects will continue to be relevant and applicable for some time.”

At first blush, the issues and projects addressed through this program don’t scream “historic preservation.” They deal with things like pedestrian access to bike trails, lighting, safety, and public art on connector streets, crowd management during festivals, and supporting vulnerable populations in urban areas. Why would the PA SHPO be interested in exploring these issues? The simple answer is that preservation of our historic communities requires those communities to be vital and utilized. That’s the entire ethos of the Main Street approach to historic preservation, so finding ways to help people continue to use and enjoy these communities seemed like a no-brainer. Julie Fitzpatrick agrees, saying “this project is a perfect pairing that supports the original intent of ‘Main Street – to encourage downtown economic development within the context of historic preservation’ – which is more relevant than ever.”

I think these designers and community partners did pretty well on that score and I’m looking forward to seeing how these ideas get implemented and replicated. You can see the full reports for the pilot projects on the PDC website.

The pilot projects included:

Easton: the Easton Main Street Initiative, part of the Greater Easton Development Partnership, and the City of Easton worked with OSD Outside on creating greater integration and connection between Centre Square, historically the hub of ongoing events and activities, in the City of Easton and the Riverfront.

The plan involves:

- Specifically, through Northampton & Sitgreaves and Scot Park to the Riverfront – “transforming corridors into journeys”, by expanding outdoor destinations for social distancing, events, and gatherings

- Strengthening the pedestrian network from the Centre to the edge, by creating safe options for crossing Larry Holmes Drives to the Riverfront

- Creating dynamic options for open streets and outdoor lounging; with a combination of temporary, movable furniture with more permanent features; offering a variety of activities, events, and options; incorporating public art & graphics to enliven and energize the space

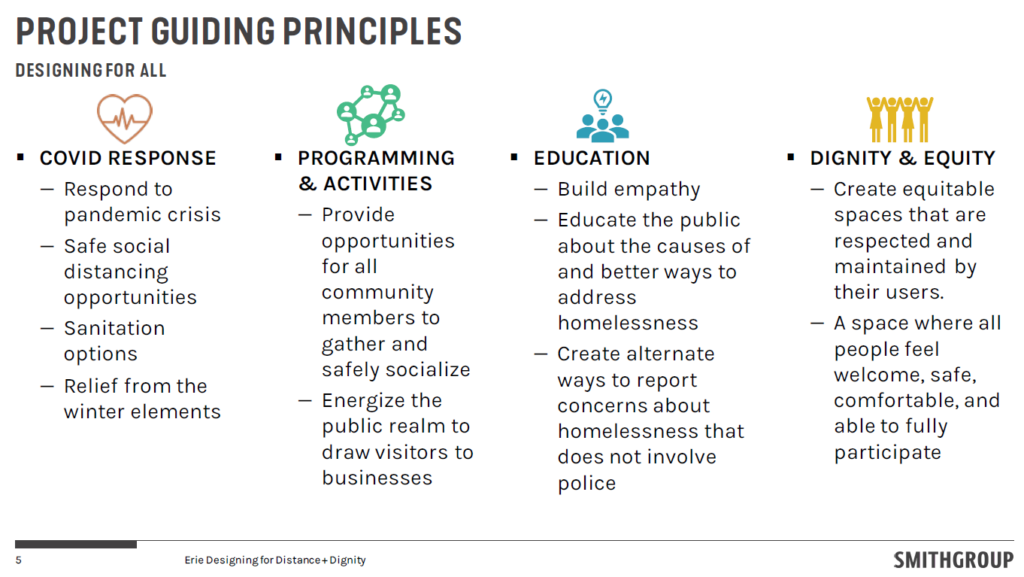

Erie: the Erie Downtown Partnership and the City of Erie worked with the Smith Group to address the need of the homeless residents of downtown by creating equitable spaces where all people feel welcome, safe, comfortable, and able to fully participate – Designing for Distance & Dignity.

The plan involves:

- Using Maslow’s Law of Hierarchy – to determine the needs and wants of the area to include: public restrooms and food lockers, warming pods and wind screens, movable furniture, charging stations, murals, and games.

- A variety of options were offered from quick, cheap, and easier tactical interventions to more expensive methods and permanent fixtures.

- Specific sites were identified that included: areas along State and French Street, the City Mission, and other pocket parks.

- Designs were included for movable and purposeful barricades that could also serve as planters, bike racks, and billboards.

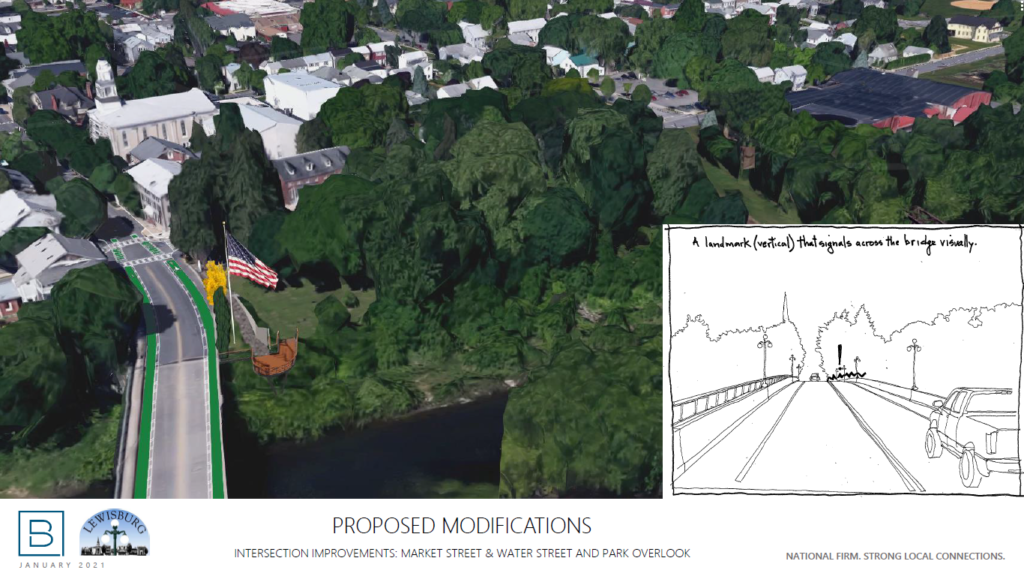

Lewisburg: the Lewisburg Neighborhood Corporation, the Lewisburg Downtown Partnership, and the Borough of Lewisburg worked with Bergmann to address the increase in outdoor activity and recreation during the pandemic, concentrating on the intersection at Market Street and Water Street, and the Susquehanna River Overlook at the edge of the downtown.

The plan involves:

- Coordination with the project team that also included PennDOT District 3.0

- Alternatives that were examined included: traffic calming, multi modal options, gateway treatments, and wayfinding with a potential signing district.

- A variety of creative options were offered to celebrate and delineate Soldier’s Park, from more traditional to natural, to artistic, playful, and interactive.

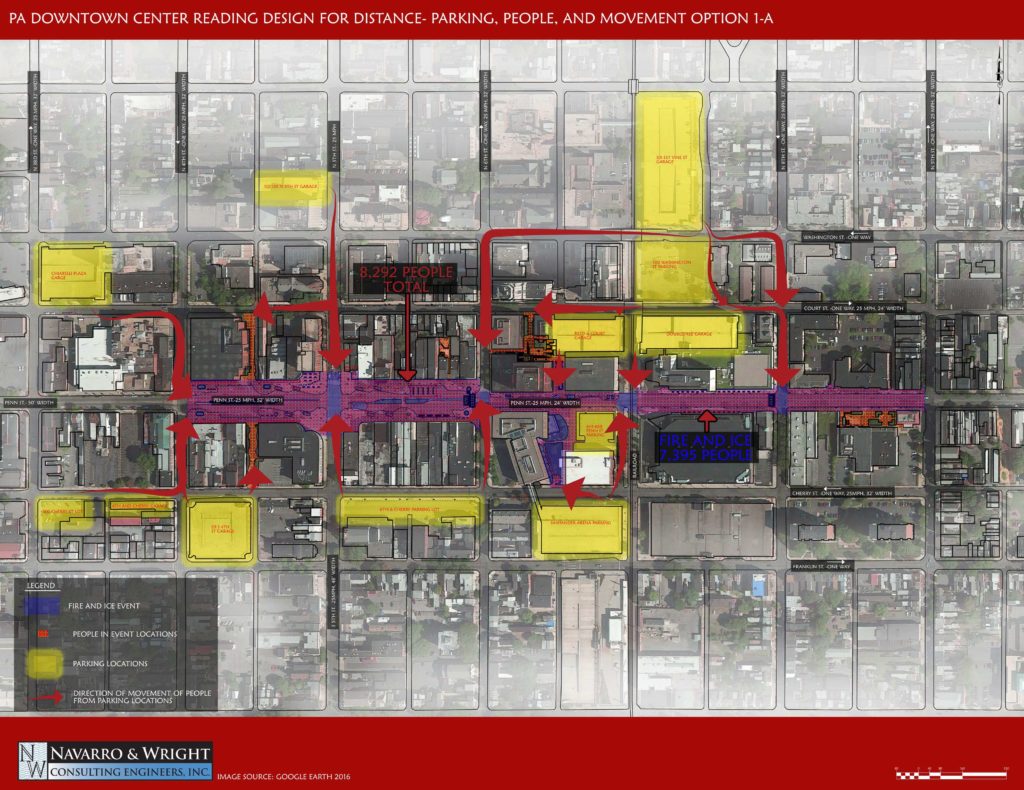

Reading: the Reading Downtown Improvement District Authority and the City of Reading worked with Navarro & Wright Consulting Engineers, Inc. to develop a strategy for safe gathering and social distancing along Penn Street between 4th and 9th Street where the majority of events have traditionally taken place. The other areas of focus are located in three courtyards along Penn Street.

The plan involves:

- Identified public parking areas, walking routes visitors would take from their car to the event, and timing of activities are incorporated into the concepts.

- Each plan contains a matrix of dots that outline the total maximum number of how many people

- can be within a general block of area in the downtown for each event at any given time, and arrows providing a guided flow of movement. Each dot is spaced exactly six feet apart for the recommended social distancing requirement.

- Fire and Ice Festival is typically the largest event, which was used as the example to include elements such as food truck design and a sequence for flow of people waiting at the food truck lines, a warming tent tunnel, improvements to the courtyard plaza spaces, and added interactive murals/digital screens.

Leave a Reply