Pennsylvania has a long and important history related to metal truss design, fabrication and erection. PennDOT’s SPIKE funding may help with their preservation as part of the commonwealth’s transportation infrastructure.

Continue readingCategory: PennDOT (Page 4 of 8)

UPDATE: Due to public health measures to limit the spread of COVID-19, effective March 30, 2020, we are no longer accepting mailed submissions.

Any previously mailed submissions should be resubmitted through PA-SHARE. Please use the process outlined for sending submissions below.

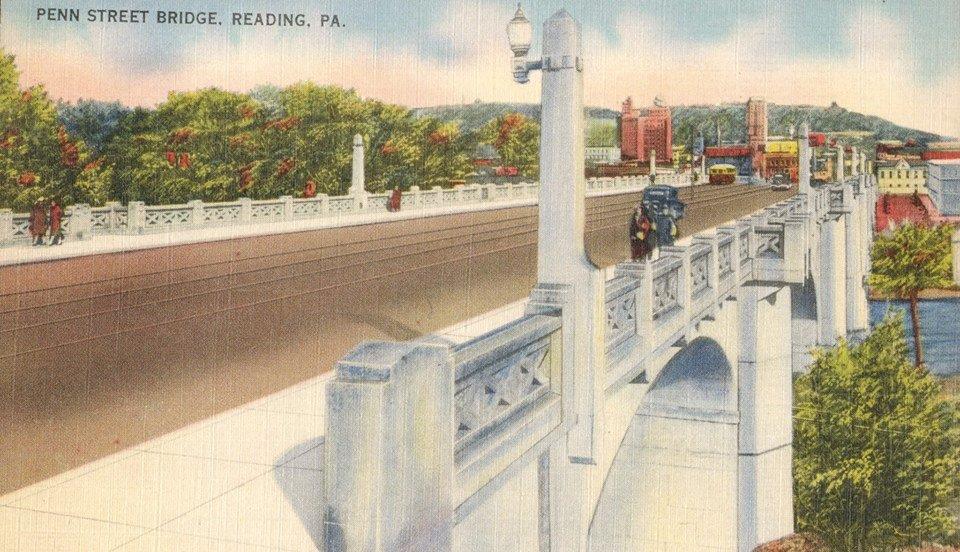

Continue readingI recently had an opportunity to talk about PennDOT’s Penn Street Bridge Project in Reading at the American Planning Association’s Pennsylvania Chapter conference this past October.

Continue readingWhen travelling between Schuylkill and Lebanon County, some may prefer to skip Interstate 81 and take the more scenic route past Swatara State Park. The park is relatively recent in its formation, created in 1987, and DCNR continues to make infrastructure improvements to provide access to recreational opportunities within the park including biking, hiking, boating, and fishing.

Continue readingRecently, you may have noticed a new data set was added to CRGIS and you may be wondering what it is. This new data set appears to be several crisscrossing and winding paths – and they are!

Continue readingThis post contains updates to the statewide agricultural context, also known as the Pennsylvania Agricultural History Project, through January 2022. The development and implementation of Pennsylvania’s Historic & Archaeological Resource Exchange (PA-SHARE) has necessitate updates to the way information is collected and provided to the PA SHPO.

Continue reading

Saving the Watts Mill Road Bridge: Part 1

The biggest obstacle for a small trail or historic preservation group to assume ownership of a historic bridge is usually funding. They operate on lean budgets and do not always have the extra resources to purchase, rehabilitate and maintain a historic bridge. However, a success story is in the making with the transfer of the Watts Mill Bridge from PennDOT to the people of Beaver County.

Continue reading

Archaeology for the People and by the… PennDOT?

Yep, you’re reading that right: the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) does archaeology! Continue reading

The Lenticular of Lazy Brook Park: Bridging the Gap between Idea and Execution

It was ten years ago, almost to the day, that I participated in a series of scoping field views for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) that involved a brilliant idea to address the needs of two seemingly separate projects. Continue reading

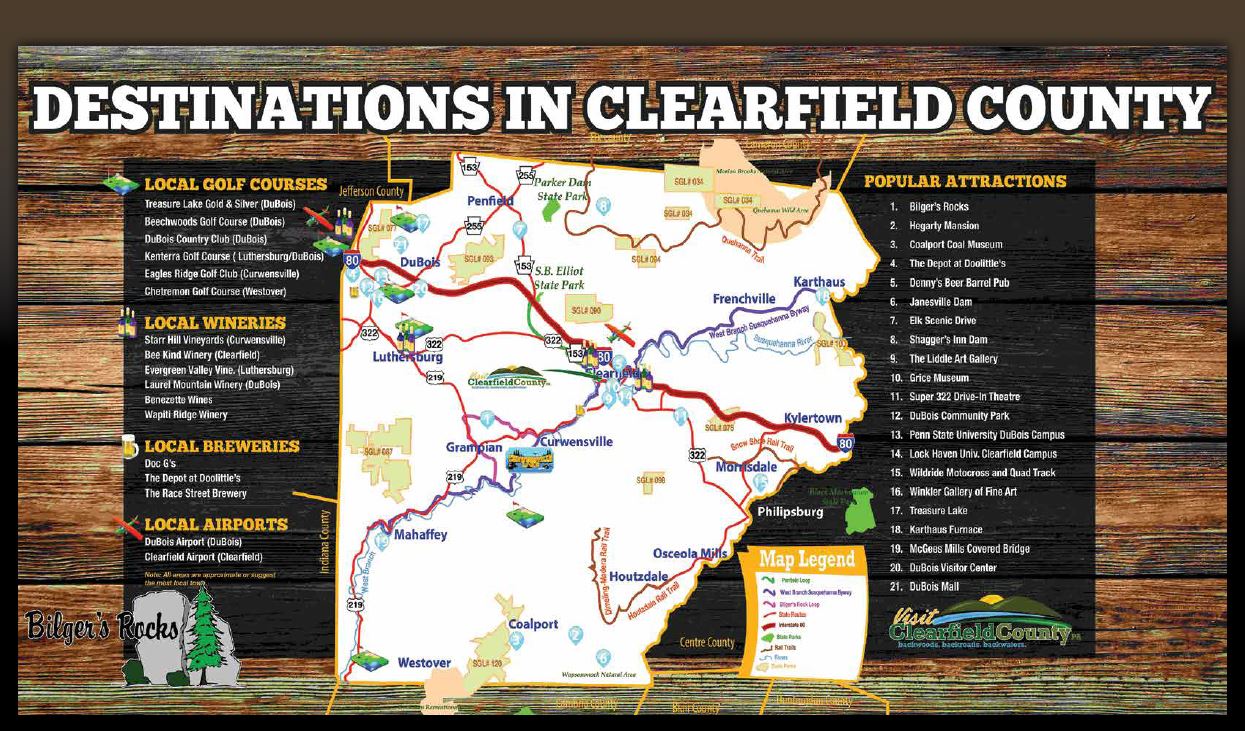

Are you looking for an adventure? Then take a drive to Clearfield County because Pennsylvania’s West Branch Susquehanna Byway is an adventure that awaits you at every turn.

What is a Pennsylvania Byway?

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) established the Pennsylvania Byways (PA Byways) program in 2001 to identify and designate corridors with cultural, historical, recreational, archaeological, scenic, and natural qualities and outstanding features throughout the commonwealth.

If you see one of these, check it out!

PennDOT’s mission for this program is to:

- support communities and local governments in achieving byway designations,

- assist with local planning efforts to maintain byway resource qualities,

- protect and preserve visual impacts,

- educate residents and visitors,

- promote tourism, and

- enhance economic development potential throughout the commonwealth.

The PA Byways program parallels U.S. Federal Highway Administration’s National Scenic Byways Program, which was created in 1991 as part of the Federal Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA). The main difference between the two programs is that Pennsylvania does not use “scenic” in its title, recognizing that many roadways exemplify more than purely scenic qualities.

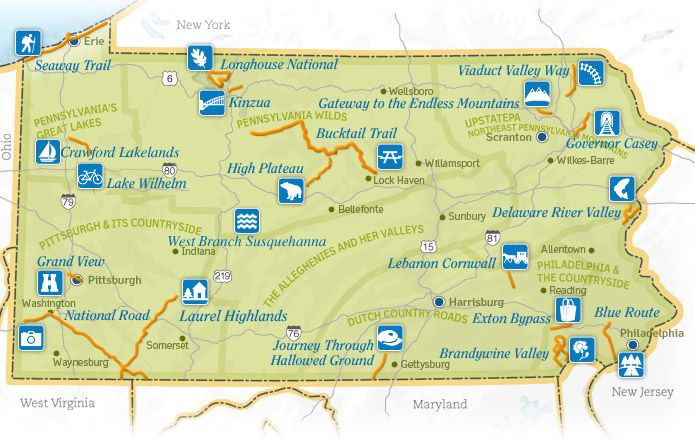

Currently, Pennsylvania has 21 designated PA Byways, one National Forest Scenic Byway, and three National Scenic Byways, and one All-American Road. The existing network of byways includes over 650 miles of roads through almost half of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties!

Take some time to explore some of PA Byways.

**The Pennsylvania Byways program is currently being restructured. If you have interest in designating a byway, please contact Jacqueline Koons-Felion at jfelion@pa.gov or 717-787-6388.**

5 Things to Do and See along the West Branch Susquehanna Byway

1. The Drive

The West Branch Susquehanna Byway offers seventy-two miles of winding roads showcasing historic, archeological, cultural, recreational, natural and scenic rarities that are inherent of Clearfield County. This byway is a great outlet for the outdoorsman, civil war buff, foodie, photographer, and the explorer.

PennDOT designated this corridor as Pennsylvania’s 19th Byway in March 2012.

Got to www.visitclearfieldcounty.org for more information!

The West Branch Susquehanna Byway is a scenic and natural beauty that is a must see. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Susquehanna River was a lifeline of historic Clearfield County. The River served as the lumber transport system that fueled the once-booming economy. The byway was named after the river because of its historical significance, but also because the byway provides access to the abundance of recreational opportunities that the Susquehanna River offers, both on its banks and in its waters.

2. McGees Mills Covered Bridge

McGees Mills Covered Bridge

This Bridge is the only covered bridge crossing the mighty Susquehanna River and the only one still being used in Clearfield County. The 122 ft. single span Burr arch truss bridge was built in 1873 by Thomas A. McGee. Thomas built the bridge using hand hewed white pine timbers from the area and at a cost of $175. It was the last covered bridge built in Clearfield County. Thousands of rafts floated under the bridge including the last raft in 1938.

The bridge was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and renovated in 1994 after a collapse caused by record-breaking ice and snow. This scenic spot remains one of the most popular photographic attractions in Clearfield County and is also located at the very beginning or end of the West Branch Susquehanna Byway.

3. Bilger’s Rocks

Clearfield County’s Bilger Rocks

Over 300 million years ago, before the settlers, before the Indians, way back when the earth was taking its shape; a city was built just outside of Grampian in Clearfield County. This prehistoric city was like none other, for it was made of massive rocks. Twenty acres of massive rocks to be exact. Some of the rocks tower of five stories high and most of them are over 20 feet thick. The geological phenomenon responsible for this masterpiece is known as frost wedging. Frost wedging causes boulders to break away from the mountainside and helped create this magnificent vision full of numinous caverns and narrow passageways that has withstood eons of vagaries. There are 170 acres of park land where the Bilger’s Rocks Association offers campsites, pavilions, picnic area, a concert arena, recreational activities and even a concession stand that is open every weekend. www.bilgersrock.net

4. Curwensville Lake

Picturesque Curwensville Lake, Clearfield County.

Curwensville Lake is a reservoir located just to the south of the town of Curwensville. The lake was formed due to the construction of the Curwensville Dam to the north of the lake. Before the dam was built, there were several floods occurring along the West Branch Susquehanna River, affecting the towns of Curwensville, and Clearfield to the north. On September 3, 1954 a Flood Control Act was passed due to the flooding along the West Branch river basin. The dam cost $20,400,000 to construct. Curwensville Lake offers many opportunities to entertain the whole family. Biking, hiking, boating, camping and fishing are just a few of the activities available at Curwensville Lake. And with no horse power regulations on the lake, visitors can enjoy the open waters with their boat and spend some relaxing time catching some of the freshwater fish.

5. Denny’s Beer Barrel Pub

Burger challenges at Denny’s Beer Barrel Pub.

Denny’s was founded by Denny and Jean Liegey in September 1977. Denny’s started making giant hamburgers to attract attention and to create a fun atmosphere for all. Denny’s is known nationally as the home of the “World’s Largest Hamburger Challenges.” It all started with a 2 lb. hamburger challenge with homemade buns baked in a coffee can and the rest is history. Denny’s became famous in 1998 for “The Ye Olde 96er” and have been featured on tv shows like Rachel Ray, The Food Network, Travel Channel, Good Morning America and many more. Guests have dined from all 50 states and many from countries around the world.

Interested in seeing and learning more?

The West Branch Susquehanna Byway is a beautiful scenic and fun byway. This is just a small taste of what the byway has to offer. Visit us in person or on our website, www.visitclearfieldcounty.org, to learn more about the West Branch Susquehanna Byway.

This week’s post is by guest contributor, Josiah Jones. Josiah is the executive director of Visit Clearfield County.

Recent Comments