A couple times each summer in the 1990’s my dad would pack us three kids into his truck and hook up the pop-up camper and head on over to ‘Pinchot’. Arrival was a ton of work which often included setting up the camper, unloading the canoe, getting a fire set to light, and finding the nearest bathhouse.

But it was the anticipation of what was to come that kept us motivated. Riding bikes through the campground, swimming in the lake, fishing until dusk, spending time with each other and taking advantage of all the possible activities before us. Our imaginations in this place were limitless. What we always just simply called ‘Pinchot’ as many locals do, this place and all those who made it possible, shaped the principles of how my siblings and I understood the natural world around us.

Gifford Pinchot State Park lies among the rolling diabase hills above the Conewago Creek in northern York County. How did this place get here? Who made this happen?

As a child, you naturally don’t understand concepts of public and private property, so giant playgrounds such as Pinchot are taken for granted. This appreciation has come much later in life when learning that parks and open space do not happen by accident, but by many people persistently advocating to make them happen. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania not only was the place where the City Beautiful Movement began and had been the cradle of conservation in the early 20th century but was a place where open space and outdoor recreation was prioritized in the mid-century. A tremendous legacy to be proud of.

Early Parks History

During the Depression in the 1930’s, the location around the “York Hills” area of Warrington Township had been identified as an ideal location for a recreation area by the National Park Service.[1] This was due to its nearly equidistant proximity between Harrisburg and York, a large metropolitan area of South-Central Pennsylvania and the natural rural beauty of the area.

Maurice K. Goddard, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters having been appointed in 1955 almost immediately began working on the development of Gifford Pinchot State Park as per the Federal Government’s recommendation. Governor George Leader appointed the competent and motivated forestry professor to develop a park within 25 miles of every Pennsylvanian. A wildly ambitious plan.

Pictured in 1958 is the 1760’s Wellen Farm, one of the many historic farms demolished for the park. Part of the wall in the foreground remains today.

Prior to Goddard being appointed Secretary in 1955, Pennsylvania’s state and forest parks and other recreation areas were largely located in remote parts of the state. While Pennsylvania, and Pinchot himself, had been national leaders in forest conservation and planning, the idea of implementing a widely accessible outdoor recreation policy was largely in its infancy. In the 1950’s in the period following the Second World War, several factors such as fewer working hours, increased automobile ownership, and increased wages allowed many Pennsylvanians to have greater leisure time thus contributing to the public need and desire for more outdoor recreational opportunities.

Goddard himself agreed when he was appointed that existing campgrounds on state lands looked like “shanty towns” as they were minimally regulated and inadequate to meet growing demand.[2] Goddard was adamant that parks are for people, and therefore parks should be located where people live and should be managed by professional staff, not by politics Gifford Pinchot State Park was Pennsylvania’s first thoughtfully and intentionally planned park to serve as many people as possible.[3] Additionally, the park’s proximity to state government in Harrisburg, made it a perfect place to test new policies in how to administer recreation and manage in what would become a golden age of new State Parks and outdoor recreation in the Commonwealth.

Goddard’s vision to professionalize the department and to expand recreation for all Pennsylvanians required money, therefore he helped with authoring and passing the Oil and Gas Lease Fund Act in December of 1955.[4] At the time, it was one of the most important pieces of legislation to expand outdoor recreation to Pennsylvanians. The lease revenue from fossil fuel extraction and storage on state owned property would fund “conservation, recreation, dams, or flood control…”

Gifford Pinchot State Park was one of the first projects funded by the Oil and Gas Lease Fund with an initial cost of just over a million dollars.[5]. The park was one of the first “Goddard style State Parks” which not only followed specific design principles and site criteria (and ultimately a distinct feeling of design and aesthetic) but also refers to the period in which the Commonwealth shifted public policy towards prioritizing outdoor recreation as a fundamental right for all Pennsylvanians. Secretary Goddard and Governor Leader in the 1950’s ushered in Pennsylvania’s golden age of State Park planning as they understood that access to outdoor recreation was a key component to quality of life in the Commonwealth. Gifford Pinchot State Park was one of their pilot projects in their effort to make parks available to all people.

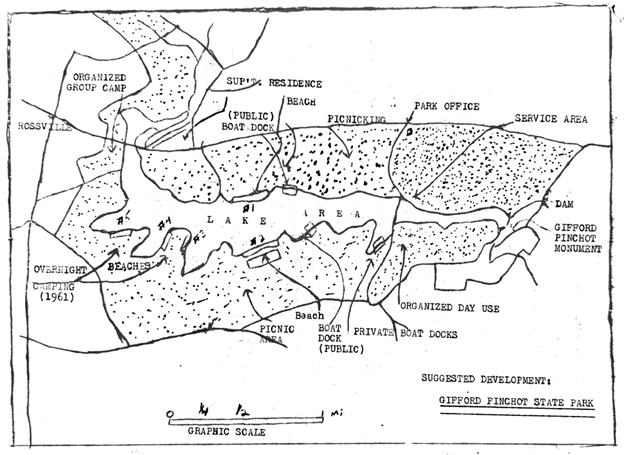

An early planning map of the suggested development and recreational opportunities at the new Gifford Pinchot State Park. Circa 1959.

Planning Begins

The proposed site location for the park met the Departments criteria for what a successful state park should include: water, accessibility, location, topography, subsurface conditions, availability, and scenic and historical interest.[6] Planning for Gifford Pinchot State Park began in late 1956 but the park was not publicly announced by Governor Leader until August 1957 during a speech in Dover, York County.[7] Appraisals and negotiations to acquire eighty-one separate properties via eminent domain for the new park occurred between 1957 and 1959.[8] These properties were almost exclusively historic farms and their associated cropland but also included some smaller residential properties dating from the early part of the 20th century. The process was not without controversy though. Most property owners reluctantly accepted payment for their properties and vacated while at least one family resisted until being forcefully removed from their property.[9]

Governor Leader, a York County native, worked alongside Goddard and named the park appropriately after Gifford Pinchot, one of Pennsylvania’s most famous governors and one of the Nation’s most famous conservationists. Another reason for honoring Pinchot, is because the macadamized road that leads to the park site was the first “Pinchot Road” in the Commonwealth. Part of a massive project to modernize Pennsylvania’s patchwork road infrastructure in the 1930’s. An important connection to make given ‘accessibility’ to the park was a primary criterion for its location.

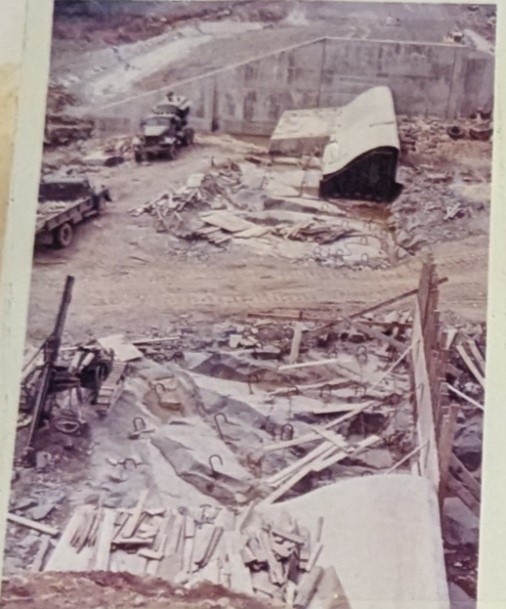

Engineering and design of the Conewago dam and spillway along Beaver Creek began in 1958 and construction began in 1959. An artificial reservoir to create a central body of water for recreation, water conservation, and flood control was almost a non-negotiable feature of nearly all of Goddard’s parks. Goddard always emphasized “A good reservoir can and must the nucleus of a park site.”[10] In addition to the task of dam construction the first half of 1959 also included clearing and burning of vegetation, demolition of farm complexes, and reservoir grading.[11]

Forming and pouring the new Conewago Dam. Circa August 1959. Courtesy of DCNR.

Two primary day use areas were designed and constructed on opposite sides of the future lake for picnicking, boating, swimming, fishing, and birdwatching. The decision to construct two distinct day use areas was a design concept first tested at Prince Gallitzin State Park and was used for the second time at Gifford Pinchot. This was to distribute traffic and to also provide a more “conspicuous and thus more aesthetic design for parking facilities.”[12] Two day use areas were also constructed to serve people driving from Harrisburg and York, thus each side were historically called the Harrisburg and York sides of the lake.

Forming and pouring the beach wall at the Conewago Day Use Area. Circa August 1959. Courtesy of DCNR.

Boat launch and mooring areas, boat rentals, walking trails, manicured lawns, concessions, roads, parking lots, and picnic areas were constructed in the day use areas. Few trails were initially planned and those that did exist had been pre-existing farm roads, fence lines, or other agricultural features. Most initial recreational opportunities relied on the nucleus of the park: the lake. The dam gate was closed in a ceremony on November 7, 1959, and the lake was filled by February of 1960.[13] The initial design features of a dam, large parking areas, manicured lawns are hallmarks of Goddard planned parks but also embody cultural ideals of recreation in the mid-20th century.

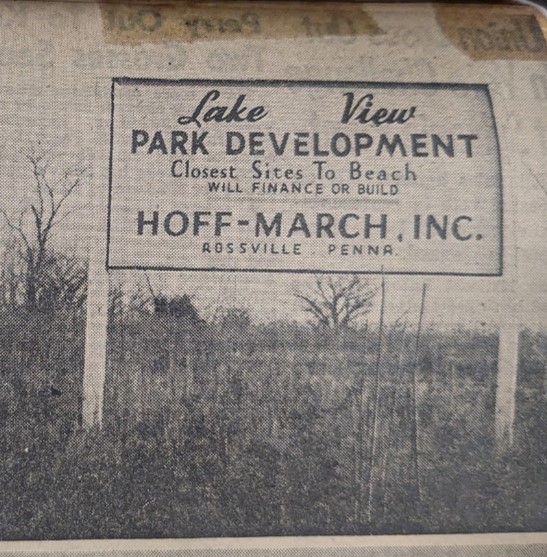

While construction was underway, land use around the future park location also began to change as property values increased and historic farms were subdivided for residential and recreational use. These properties were marketed for their “lake side view” and their proximity to “fresh air, swimming, fishing, and skating.”[14]

A sign for recently subdivided farmland along Alpine Road in 1960.

This nearly immediate change in land uses around the park is evidence that Pennsylvania’s outdoor recreation economy has been thriving for generations and proximity to outdoor recreation is an indicator of quality of life. For example, Forrey’s “Auto Treat” drive-in opened in late spring of 1960 to provide snacks, ice cream, and beverages to park visitors and continues to operate today. These economic arguments for parks was one that Goddard made throughout his career. [15]

A current photo of a house within the advertised subdivision constructed circa 1961.

Opening the Park

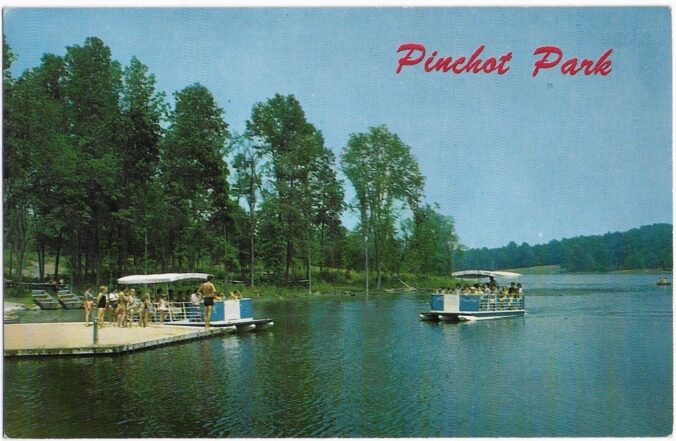

Gifford Pinchot State Park officially opened on May 26, 1961, a year behind schedule. Governor Lawrence dedicated it as the Commonwealth’s first state park to “give major communities quick access to rural recreation facilities.”[16] By Independence Day in 1961 over a quarter million people visited the new state park and filled a desperate recreational need for the region.[17] Construction projects and ongoing upgrades at the park continued through the 1960’s and early 1970’s. One of the first improvements, as per complaints from visitors, was to upgrade the turf and stone beaches to fine sand for the summer of 1962. Construction and installation of a toboggan slide was completed in 1963 and the installation of four nature trails in 1965.[18]

Quaker Race Day Use Area in May 1961. Courtesy of DCNR.

As recreational opportunities continued to expand at the new park so did its visitation. In Gifford Pinchot State Park’s first year the park attracted around 650,000 visitors.[19] Visitation would continue to increase in part due to the Fish and Boat Commission opening the lake for fishing for the first time in July of 1962 as more than “2,000 hook and line artists spilled all over the beautiful lake…”[20] Hunting was not initially permitted at the park through the 1960’s due to potential conflicts with ongoing construction but was finally opened September 27, 1969 and allowing for yet another opportunity to recreate.[21]

First camping season at the park in July 1969. Courtesy of DCNR.

With this many people enjoying the park, the desperate need for modern sanitary facilities was addressed. Modern sewage and water access were completed in 1965 while a second phase to construct comfort stations and an all-season shelter was to be completed by 1967.[22] The next phase of work was to construct a campground at the southwestern end of the park. In 1968 work began to demolish a historic farm complex to construct 350 campsites, seven wash-houses, a dumping station, and an entrance station which would accommodate both tents and trailers.[23] The campground was completed at the cost of $627,000 and was opened on April 10, 1969.[24] Due to its popularity and heavy use, the campground justified the need for additional improvements including parking facilities, concrete boat launching ramps, first aid stations, and playgrounds all of which were constructed and available for use by 1973.[25]

The last original ‘comfort station’ in the park built in 1966.

One of several washhouses in the campground built in 1968. Both this building and the previous represent 1960’s recreational architecture.

Guided nature walks, birdwatching, and wildlife education lessons were popular activities as the 1960’s progressed and as the public became more environmentally aware.[26] Nature trails were incrementally added through the 1960’s with the help of volunteer groups and were primarily intended for nature education programming. Goddard stressed that wildlife education should be part of programming at State Parks as an informed public about the natural world will naturally value and care for it into the future.

This 1969 photograph shows the nature center as it was initially constructed as an all-season shelter for visitors in 1967.

Gifford Pinchot State Park was slated to receive a “nature center” as a capital improvement project which would serve as the park’s classroom.[27] What was previously the all-season visitation shelter constructed in 1967 would become the Nature Center, when it’s first exhibit opened in August of 1969.[28] Since it’s opening, the nature center has been laboratory using the park as a living experiment to educate tens of thousands of young minds about the beauty, science, and fragility of the environment.

The nature center has been in use by educators and artists since 1969.

Continuing to Evolve

By the mid-1970’s the park and its large-scale physical infrastructure was generally complete, but policy changes in Harrisburg continued to improve recreational experiences at the park. Electric powered boats were permitted in many of the Goddard planned parks including Gifford Pinchot in 1972.[29] Another significant policy change occurred when the campground changed from a first-come first-serve system to a reservation system in 1975. This change made it much easier for campers to plan their outings instead of being turned away when arriving at the park with a truck full of kids.[30] To cap off the decade, in 1979 policy changed to allow for winter boat storage at the park. This policy eliminated the need for regular visitors to continually transport smaller watercraft every season.[31] Lastly, by 1980 several miles of equestrian trails were constructed by local volunteers eager to have trail riding in the park.[32] Although simple, these policy changes and volunteer projects are as impactful to an experience as the big earth moving projects.

The park and its recreational opportunities would increasingly become more accessible for those with disabilities following the National Handicapped “Camp-O-Thons” held at the park between 1980 and 1982. Camp-O-Thon was a national event funded by the federal government through the Department of Welfare and provided an opportunity for individuals with disabilities to engage with each other in outdoor activities including boating, fishing as well as arts, crafts, and music. The event also had a dual purpose and served as a way for the Commonwealth and park staff to better “understand the needs, desires, and abilities of the handicapped” and how parks can be adapted to better suit the needs of all Pennsylvanians. For example, during several daylong events park staff experienced barriers related to wheelchair accessibility and the inability for participants to charge their wheelchairs and other assistive equipment.[33]

Program from 1980 Camp-O-Thon.

While the Camp-O-Thons were successful, the apparent lack of infrastructure for participants were important lessons learned when considering future improvements to the park. In the summer of 1982 accessibility improvements were made in the park including access ramps, wider doorways, paved trails, and accessible rest rooms. In 1986, ten cabins for overnight stays to accommodate those who may not be able to camp were constructed by the Pennsylvania Conservation Corp.[34] Significant improvements which removed barriers for Pennsylvanians to experience the park and its recreational opportunities.[35]

As the decades would pass, Gifford Pinchot State Park would develop alongside its visitors like old friends growing up together. Previously fallow and smooth pastures would turn into groves of prickly eastern cedar and goldenrod while old scraggly farm woodlots would evolve into mature examples of oak, hickory, and poplar forests. Naked diabase scattered campsites would slowly fill in with mature canopies where thousands of marshmallows would be toasted beyond edibility. Gifford Pinchot State Park would be where millions of Pennsylvanians would go to make memories, spend their leisure time, reflect upon life’s great mysteries, and the passage of time.

Conewago Day Use Area, Gifford Pinchot State Park. July 2024.

Generations after generation reference these experiences at Gifford Pinchot State Park as reminders of the good old days. Goddard, Pinchot, and all those who have worked to conserve resources and to make outdoor recreation accessible for Pennsylvanians should be celebrated. Their contributions, and perhaps sacrifices, have provided us with places like Gifford Pinchot State Park. A place which I like to call one of my dearest of friends.

_______________________________________________________________

[1] Planning for the Future of the Harrisburg Area: Report of the Regional Planning Committee; Municipal League of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: 1939-1940.

[2] Ernest Morrison, a Walk on the Downhill Side of the Log: The life of Maurice K. Goddard, The Pennsylvania Forestry Association, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 2000.

[3] William C. Forrey, History of Pennsylvania’s State Parks, Department of Environmental Resources, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 1984.

[4] Ernest Morrison, a Walk on the Downhill Side of the Log: The life of Maurice K. Goddard, The Pennsylvania Forestry Association, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 2000.

[5] Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Forests and Waters Biennial Report, May 31, 1958.

[6] Standards for Park Site Location, Pennsylvania’s New State Parks: A Report to the General Assembly on Act 256, Department of Forests and Waters. July 1959.

[7] Northern York County Game and Fish Association, Inc. Quarterly News Letter, October 1957.

[8] Doylestown Intelligencer August 28, 1959.

[9] York Sunday News, York, PA, Summer 1959.

[10] Doylestown Intelligencer, Doylestown, PA, August 28, 1959.

[11] Altoona Mirror, Altoona, PA, May 27, 1959.

[12] Ernest Morrison, a Walk on the Downhill Side of the Log: The life of Maurice K. Goddard, The Pennsylvania Forestry Association, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 2000.

[13] Record Harald, Waynesboro, PA February 20, 1960.

[14] New Oxford Item, New Oxford, PA, January 29, 1959.

[15] The Gazette and Daily, York, PA, January 25, 1960.

[16] Dan Cupper, Our Priceless Heritage: Pennsylvania State Parks, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1993.

[17] Kittanning Simpsons Daily Leader Times, Kittanning, PA, July 6, 1961.

[18] Hanover Evening Sun, Hanover, PA, December 28, 1961.

[19] Gettysburg Times, Gettysburg, PA, August 9, 1962.

[20] Pennsylvania Angler, Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, Harrisburg, PA, August 1962.

[21] Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters, Gifford Pinchot State Park hunting map, August 1969.

[22] Gettysburg Times, Gettysburg, PA, August 5, 1966.

[23] Gettysburg Times, Gettysburg, PA, April 23, 1968.

[24] The Evening Sun, Hanover, PA, March 11, 1969.

[25] Huntingdon Daily News, Huntingdon, PA, January 6, 1972

[26] Lancaster Farming, Lancaster, PA, April 20, 1968.

[27] The Evening Sun, Hanover, PA, October 3, 1967.

[28] The Gazette and Daily, York, PA, August 16, 1969.

[29] Indiana Evening Gazette, Indiana, PA, May 22, 1972

[30] The Evening Sun, Hanover, PA, March 4, 1975.

[31] Hanover Evening Sun, Hanover, PA, October 12, 1979.

[32] York Daily Record, York, PA, November 6, 1979.

[33] Kittanning Leader Times, Kittanning, PA, April 21, 1980.

[34] York Sunday News, York, PA, April 6, 1986.

[35] The York Dispatch, York, PA, August 5, 1982.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

What a great article! I never knew the history behind the development of Pinchot State Park.

A well-researched article full of interesting details. The role of professionals, free from political pressures, in developing the varied uses of the park is an important lesson for our times. We would be wise to support professionals in their jobs rather than require them to pledge allegiance to a political leader. Kudos to the writer!

Thank you for writing up a short history of Pinchot Park! I belong to a rowing and sculling club that has made the park home for a little over 30 years. The park is a gem.

I cried reading this article. The destroyed history is heartbreaking.