I’ve been lucky enough to visit the idyllic George Nakashima Woodworkers property in Solebury Township, Bucks County three times, once for “work” but each time a genuine pleasure, and I will jump at any chance to return. I hope this deep-ish dive into the story behind George Nakashima and his property inspire you to learn more and visit.

The Nakashima complex (PA-SHARE Resource #2007RE01239) was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2008 and designated a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service (NPS) in 2014, one of 169 NPS “Landmarks” in Pennsylvania.

The George Nakashima Woodworkers complex began with a workshop in 1946 and expanded into a compound serving as workshops and studios, family homes, lumber storage areas, and galleries. George Nakashima was a talented architect who early in his career turned his focus to furniture design, and preferred to be called a “woodworker.”

George’s daughter, Mira, explains in her book Nature Form & Spirit: The Life and Legacy of George Nakashima that her father had a great respect for engineering and a deep understanding of materials, and believed that the best architecture creates a sense of harmony, betters society, and enters the realm of art.

Through his artistry, and mastery of proportion and engineering principles, Nakashima was able to create a compound where the interior and exterior spaces are integrated with the setting, and produce a feeling of peace and tranquility. He applied the same architectural theories he followed to his furniture design, resulting in works that reflected his belief in living in harmony with nature, and allowing the materials to speak for themselves with a minimum of intervention. While he sought to retain control over all aspects of design and construction, to ensure the quality of the process and end products, he worked in partnership alongside the carpenters, builders and craftsmen executing his designs.

Throughout her book Mira emphasizes her father’s desire to create a tranquil environment for both his work and family, enhancing the beauty of the designed spaces while preserving the natural environment. Visitors to the property can experience firsthand her explanation that for her father, “architecture and furniture design were not merely a means for living, but a way to live” (page 19).

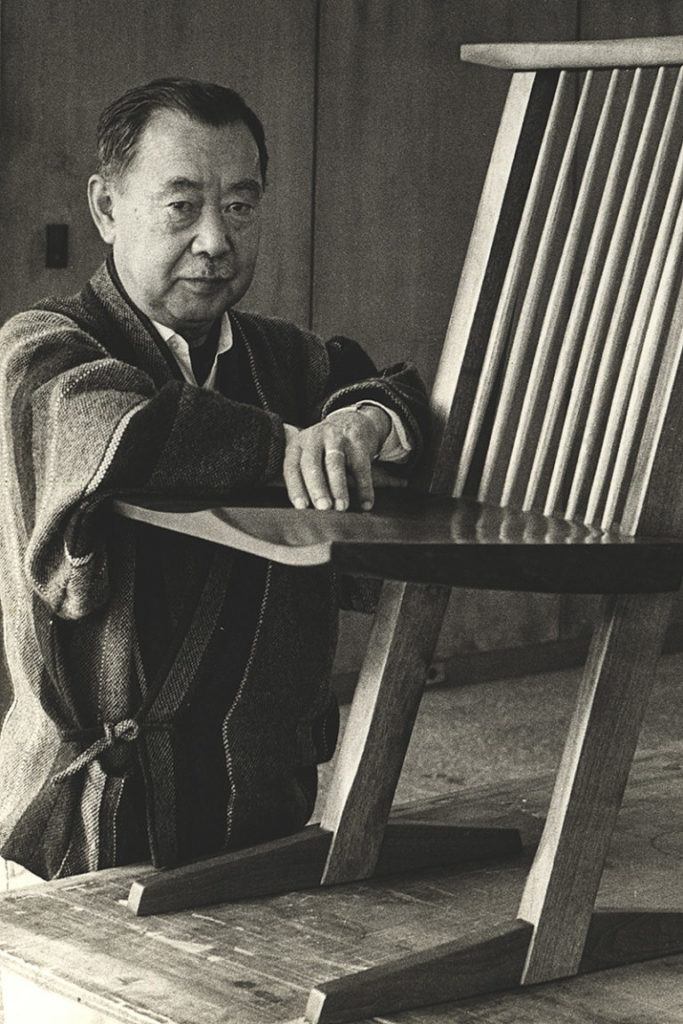

George Nakashima

Born in Spokane, Washington, in 1905 to parents who both emigrated from Japan, George was a Boy Scout who loved exploring the woods of the Pacific Northwest, earning the rank of “Eagle” scout. He studied forestry at the University of Washington before switching to architecture, and was awarded a scholarship to study at the École Américaine des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleu, France. He graduated in 1929, and chose to continue on at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) instead of Harvard, where he had also been accepted, seeking a Master’s program in architecture that was based in engineering, which he completed in 1930.

He spent a few years as a muralist and an architectural designer in New York, until in 1933 he sold his car to buy a steamship ticket to Paris, deciding to try to earn a living elsewhere during the Great Depression. Two buildings he experienced in Paris are believed to have had a great influence on him—the cathedral at Chartres, and Le Corbusier’s Pavillon Suisse, which was under construction near his rented room. In 1934, he left Paris for Tokyo.

There, he found work in the firm of architect Antonin Raymond. Raymond had been invited to Tokyo in 1920 to help Frank Lloyd Wright finish the Imperial Hotel, and Raymond decided to stay and establish his practice there in partnership with his wife, designer Noémi. Raymond worked closely with Japanese builders and craftsmen, incorporating their building traditions into new technologies and materials.

In 1937 Nakashima represented Raymond’s firm in Pondicherry, India, serving as on-site architect and general contractor for Golconde, the dormitory of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, a Hindu religious community. This was to be the first reinforced concrete structure built in India. The Ashram’s philosophy had a strong influence on Nakashima, providing him with a spiritual adventure (as Mira explains in her book) as well as a deep understanding of building with concrete and an opportunity for production of some of his earliest furniture designs.

After two years, and as international tensions mounted, Nakashima returned briefly to Tokyo. There he met Marion Okajima, also Japanese-American and a graduate of UCLA, who was there teaching English. They both returned to the US, married in 1941 and settled in Seattle, where Nakashima worked as an architect, designing furniture part-time.

In 1942, soon after the birth of their daughter, Mira, the Nakashimas and their extended family were interned with other Americans of Japanese descent in the Minidoka internment camp in the Idaho desert. Minidoka was one of ten isolated centers that housed nearly 120,000 Japanese or Japanese Americans “relocated” from their US homes during WWII. While in the camp, Nakashima worked with Gentaro Hikogawa, a carpenter who furthered Nakashima’s skills with traditional Japanese hand tools and wood joinery.

Noémi and Antonin Raymond had left Tokyo in 1938 and moved to a farm near New Hope, Bucks County, where they created a home and studio on the working farm (now operating as the Raymond Farm Center). The Raymonds were contacted by one of Nakashima’s former MIT professors, and they offered to sponsor the Nakashima family to facilitate their release from the Minidoka camp. The Raymonds were able to sponsor Nakashima as a farm worker, not an architect or furniture designer, as agricultural workers were one of the few categories acceptable for sponsorship. While he worked with the farm daily, the Raymonds also provided him with space for a small workshop.

Arrival in Bucks County

The Nakashimas arrived at the Raymonds’ farm in 1943. Although he had a small space to work on the Raymonds’ property, after a year or so he set up a workshop of his own in a rented property nearby. By 1946 he had acquired the wooded, south-facing property on Aquetong Road near New Hope where he built his first workshop, and then a home for the family, and eventually the compound still in operation today. His wife, Marion, was his business partner and helped grow the company into one employing a team of craftspeople, some who worked with them for decades. Their son, Kevin, would also play a role in maintaining the company’s legacy. George Nakashima helped take studio furniture design and production in a new direction post-World War II.

Between 1945 and 1954, prominent modern furniture manufacturers Hans and Florence Knoll produced a selection of Nakashima’s designs, which appeared alongside those of other noted modernists including some who became friends: sculptors Harry Bertoia and Isamu Noguchi. High-end furniture manufacturer Widdicomb-Mueller of Grand Rapids, Michigan, likewise produced suites of Nakashima furniture between 1957 and 1961. While mass production didn’t suit Nakashima’s sensibilities, the experience with Knoll and later Widdicomb-Mueller helped him understand how craftsmanship and industry could work together.

Mira’s book is full of photos of her father’s designs from throughout his career, as well as the buildings that make up the Nakashima compound. Nakashima embraced traditional Japanese building principles that emphasized the natural landscape and use of indigenous materials while also experimenting with new innovations, like warped-shell technology that enabled the spanning of larger areas with little material, to create unusual roof structures.

Nakashima’s fascination with experimental roof design is evident throughout the complex, especially the 1957 Conoid Studio, named for its conoid roof, and the 1967 Arts Building (also known as the Minguren Museum), which has a plywood hyperbolic paraboloid roof that is the focus of a Getty Foundation grant to enable the University of Pennsylvania to develop a conservation plan for the building.

The Arts Building was intended to serve as a gallery and exhibit space, with the first exhibit dedicated to Ben Shahn, who worked in many mediums and was best known for his realist style and social messaging. The Nakashimas had a close friendship with Ben and his wife (and fellow artist) Bernarda, and George designed additions and furniture for the Shahns’ house in New Jersey. Another close family friend was sculptor and designer Harry Bertoia, who Nakashima met through his early work with Knoll. They traded works of art and furniture, with several Bertoia sculptures at the Nakashima compound, and Nakashima furniture in the Bertoia family home in the Barto area of eastern Pennsylvania.

In his review notes for the National Historic Landmark nomination, Bill Whitaker explained that while the influence of Japanese traditions can be seen (often superficially) in the work of various international architects earlier in the 20th century, Nakashima was one of the first to bring a full knowledge of these traditions into play. The work of Nakashima, Antonin Raymond, and others they worked closely with integrated Japanese traditions in a much more substantial, enduring, and distinctive way. Their work constitutes “the most significant examples of the cross-fertilization of Modern Architecture (from the 1920-1960 period)” and “one of the most significant examples of artistic-interconnections between Japan and the US.” They systemized an approach that allowed them to integrate age-old Japanese building traditions with modernism.

Influence

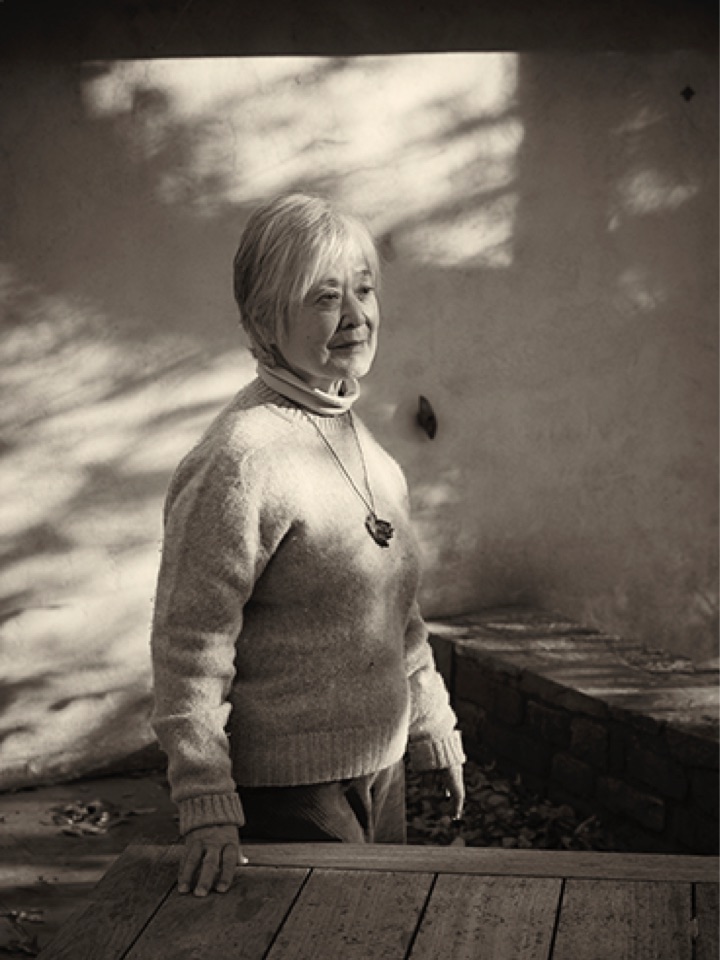

George and Marion’s daughter, Mira, is herself an architect, apprenticed with her father, and took over the business following her father’s death in 1990. She supervised the staff in carrying on George’s vision, including reviving decades-old designs, and integrated her own designs into the catalog. Her accomplishments are worthy of a separate blog post.

The homes and studios of two other furniture makers that are most-often mentioned in comparison with George Nakashima also offer tours. Sam Maloof, of California and Wharton Esherick, a Pennsylvanian whose home and studio is also a National Historic Landmark and absolutely worthy of a visit. I would definitely add Maloof’s home and studio to an itinerary for a California trip if I get the chance, but until then I may just need to plan return visits to the Nakashima and Esherick properties for my fix of inspirational vision and remarkable skill.

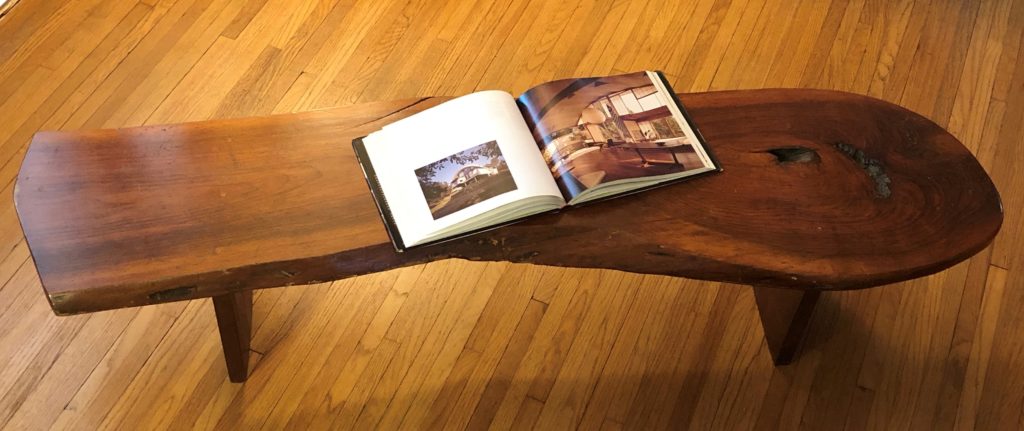

Nakashima’s works have influenced countless other woodworkers, including Ed Child, a cabinet maker from Point Pleasant, Bucks County, not far from the Nakashima studio. The bench that visitors encounter immediately upon walking through my front door was acquired by my in-laws from Child in the mid-1970s, and “confiscated” by my husband from his older brother in the 1990s. I’m not sure of the details, but I’m glad it ended up in our household!

Learn more

If you’re looking for inspiration, consider a scheduling a visit to the George Nakashima Woodworkers property. I guarantee it will lift your spirits, as it does mine. Tours of George Nakashima Woodworkers are available only by appointment, and the remaining 2021 dates are all booked. Learn more:

https://nakashimawoodworkers.com/

Watch the virtual tour presented by Mira Nakashima:

https://nakashimafoundation.org/virtual-tour/

Watch the new documentary about George Nakashima:

https://nakashimadocumentary.com/

The Nakashima compound is also home to the Nakashima Foundation for Peace. Learn more George Nakashima’s amazing altars for peace:

https://nakashimafoundation.org/

Visit the National Park Service website to read the National Historic Landmark nomination for the Nakashima complex:

https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/cb995759-75e4-425c-9b39-17bb6de164a4.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

April,

Thanks for the deep dive into Nakashima. Great blog post. I can’t wait to visit the site again and wish for a Nakashima piece of furniture to end up in my home.

Scott Doyle

I met him several times at an artist’s colony in Buck’s Co (may be the same place). We discussed his style of working with finished horizontal tree cuts to create tables. I didn’t really appreciate his work at the time, but realized later how popular he has become even seeing his work bringing high dollar on Antique Road Show, among other places.