If you use Pennsylvania’s Cultural Resources GIS (CRGIS) on a regular basis, you already know that it is an invaluable resource for preservation planning and research– a one-stop shop for survey and inventory information on more than 130,000 historic properties across the state.

You may also have noticed a number of recent improvements that have made CRGIS a much more user-friendly system than it once was. Its map navigation tools are now more intuitive and streamlined, its multiple layers are easier to filter, and many more property files have been digitized and linked to the system. This 2017 post and this 2018 post can give you some additional information about the improvements.

For existing users– mostly preservation professionals– who have already tamed CRGIS’s once-steep learning curve, these improvements are a welcome convenience. But for first-time users and non-professionals, the new CRGIS interface represents an incredible new discovery tool.

For the last four years, I have taught the “Historic Preservation Research Methods” course at Temple University, introducing undergraduate architecture students to the resources and methods used in archival research and preservation planning.

Every year, I devote at least one class session to CRGIS, explaining its search features and exploring the resources (National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility, etc.) that students can access.

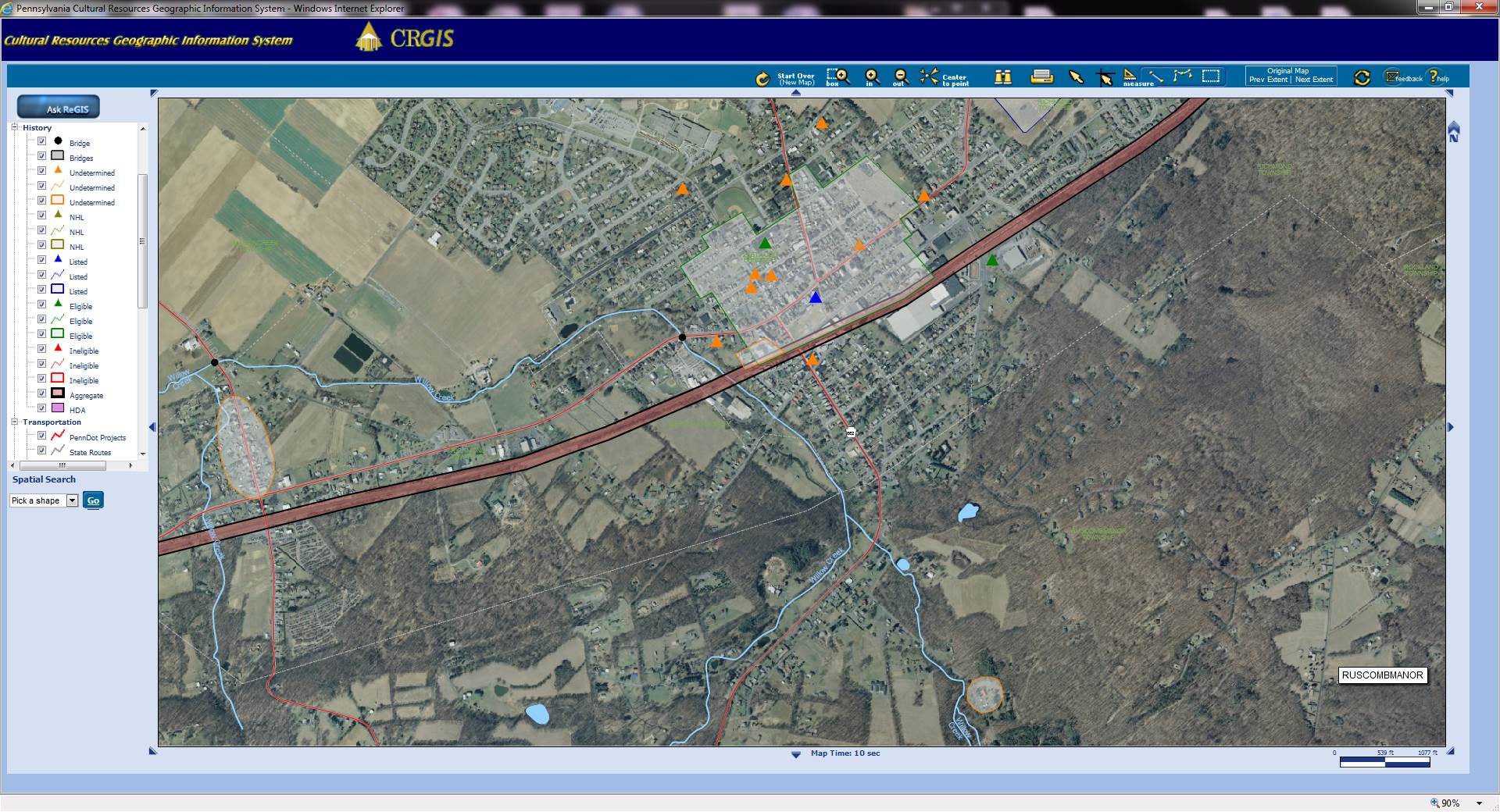

In years past, this introduction usually took the form of a tutorial, with students patiently but passively watching me navigate the system, perform searches, and explain the numerous quirks and pitfalls of the interface. The demonstration usually concluded with some version of a standard disclaimer: “Trust me– if you spend some time getting used to this, you can learn a lot!” Some students did eventually become proficient with the system, but the overall impression of many was a slow-loading screen filled with a dizzying array of cryptic shapes and inscrutable terminology.

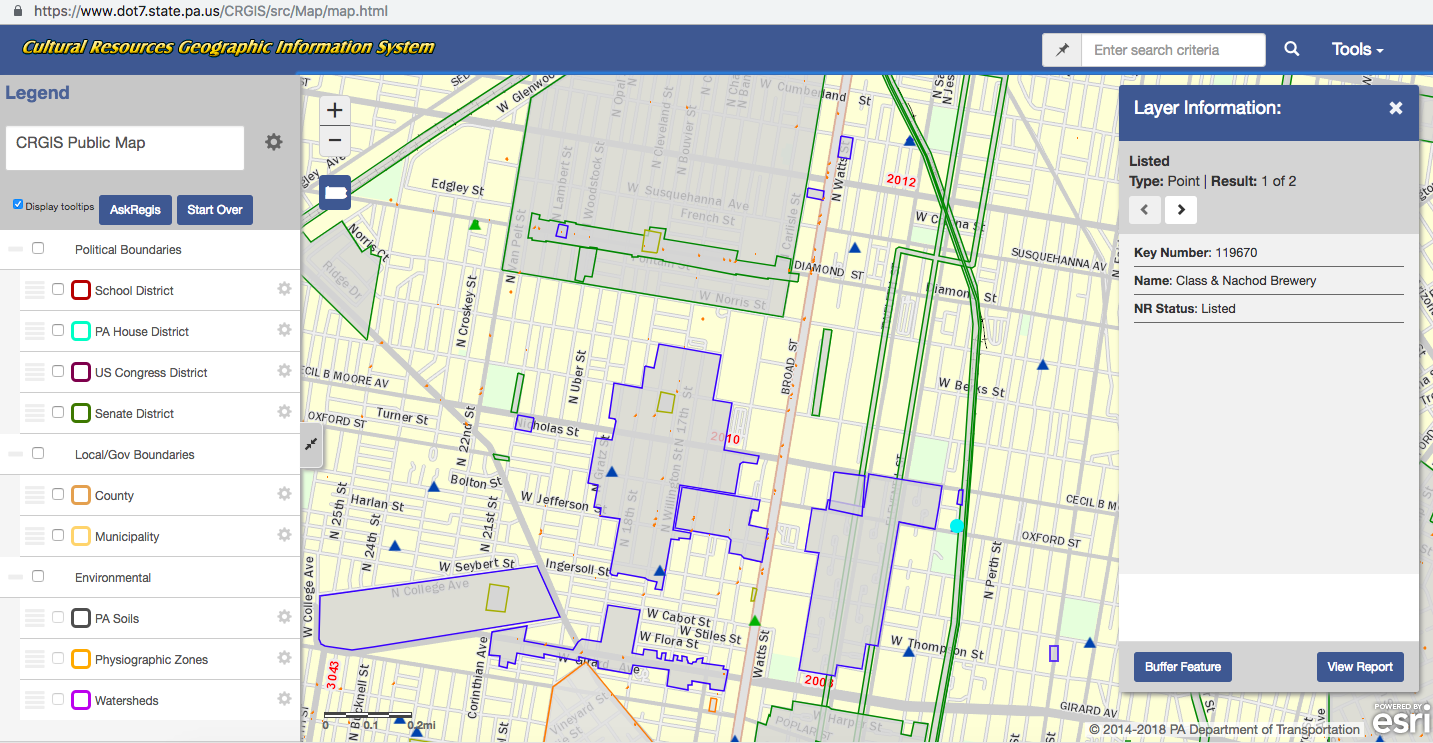

Screenshot of a CRGIS search in North Philadelphia.

With the new and improved CRGIS, however, this year’s class had an altogether different experience.

As usual, I started my presentation with an overview of different search functions and sample queries, but noticed almost immediately that my students were not just passively following along. With the system’s improved mapping tools and layer management, they were performing their own searches almost immediately on their now-ubiquitous laptops, and coming up with some excellent questions and topics for discussion.

One student was thrilled to discover that a building near Temple’s campus– one she was long curious about– was listed in the National Register of Historic Places and was originally built for the Class and Nachod Brewery (Key #119670).

The former Class and Nachod Brewery on Temple University’s campus in North Philadelphia is now student housing.

Converted into apartments as a tax credit project in the early 2000s, another student in the class had actually lived in the building for a year without knowing its history!

Other students followed this discovery with searches of their own current and former homes across the state. One found the neighborhood she grew up in had been determined ineligible for listing in the National Register. Not necessarily surprised, but still wondering why such a determination had been made, she clicked through the property report to find information related to a road-widening project (which she remembered from her childhood!). This discovery led naturally into an interesting discussion about the Section 106 process, areas of potential effect, and criteria of significance.

Yet another student exploring her current North Philadelphia neighborhood perceptively noticed and wondered why such a large percentage of National Register-listed properties were either former industrial buildings or schools. This led to a discussion of thematic districts and multiple property documentation forms, and specifically their role in encouraging tax-credit projects like the recent rehabilitation of the Quaker City Dye Works (Key #156759) into affordable teachers’ housing.

We then compared this project to another recent industrial conversion, the former Smaltz Building (Key #128788), into the Goldtex Apartments. Though this building was also listed in the National Register of Historic Places, it was not redeveloped as a historic tax credit project. A lively discussion about design review, federal vs private undertakings, and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards soon followed.

The Smaltz Building before rehabilitation. Image by Smallbones – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10470950

The Smaltz Building is now known as the Goldtex Apartments. Image from https://www.goldtexapartments.com/building.html

While I have always made a point to introduce my students to these key concepts in preservation planning, never had they all arisen so naturally and spontaneously from student-led explorations of CGRIS data. One of my main objectives in structuring my course is to foster a sense of curiosity about the built environment and expose students to the resources available to satisfy this curiosity. While CRGIS has always had a place in my syllabus, the recent improvements to its public interface have made it a particularly effective new classroom tool.

Today’s post is by guest author Ben Leech. Ben Leech is a historic preservation consultant and architectural illustrator based in Philadelphia and Lancaster. From 2010 to 2015, he was advocacy director for the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. He is a regular contributor to Extant Magazine and Hidden City Daily, and sits on the board of DOCOMOMO-Greater Philadelphia Chapter. He currently teaches a Preservation Research Methods course at Temple University, and has previously taught architectural history, archival research, and building documentation at the University of Pennsylvania, Franklin & Marshall College, Philadelphia University, and Rutgers University Camden. In 2017, he founded Archivolt Press and published two postcard books of his sketches, 36 Views of Philadelphia and 36 Views of Lancaster PA.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

Excellent article! So glad to hear how CRGIS is reaching a broader audience and informing the understanding of the built environment in Pennsylvania. The before and after rehab photos were rather eye-popping too!