In 1823, a blacksmith named John W. Miller moved into what is now southeastern Blair County with his wife, Mary, and their three-year-old son, James. In their first years there they built their house and a small blacksmith shop along an existing road between Bedford and Rebecca Furnace. They didn’t have neighbors in those early years, but that wouldn’t last long.

The location they chose near to Rebecca Furnace was significant and deliberate. In the first half of the 19th century the Juniata Valley (including Rebecca Furnace) was the center of the United States iron production, thanks to an abundance of both iron ore, limestone, and timber to use for charcoal.

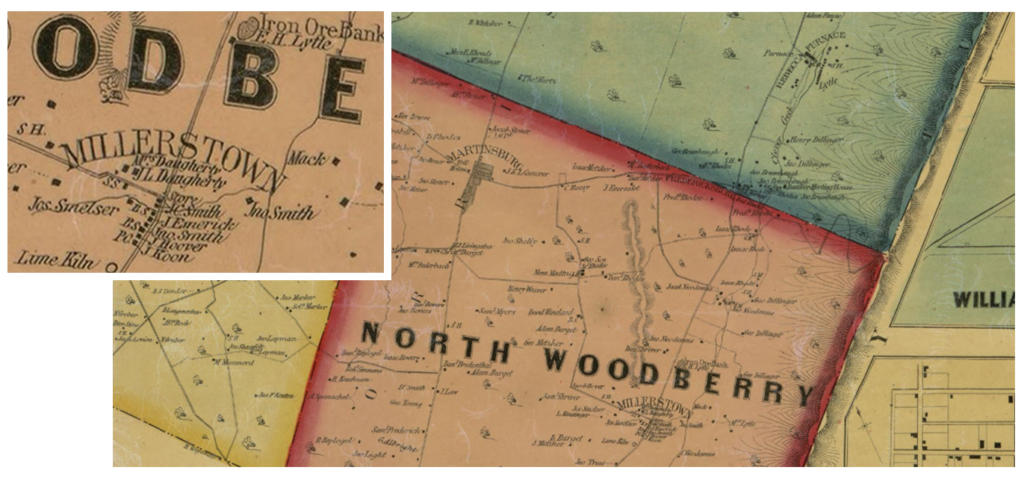

John Miller setup his blacksmith shop immediately beside a primary iron ore deposit used at Rebecca Furnace. So though they had no neighbors in 1823, by the 1850s an entire town had been established around them – known as Millerstown.

The widespread availability of low-cost iron produced in the Juniata Valley, and later all across Pennsylvania, forever changed American life. It also created an immense demand for blacksmiths by the middle of the 19th century. Nearly every town in 19th century Pennsylvania had at least one village blacksmith like John Miller.

These village blacksmiths were jack-of-all-trades craftsmen whose roles shifted based on community needs from the 1600s until the early 1900s. It can be hard, if not impossible, to decipher what those needs were based on historic records alone – but here the archaeological record can fill in some gaps.

Archaeology of the Miller Blacksmith Shop

The archaeological evidence of John Miller’s blacksmith shop was first identified during a Phase I archaeological survey for a Pennsylvania Department of Transportation bridge replacement project. Sealed beneath a strawberry garden, excavations at the site in 2016 and 2017 identified thousands of blacksmithing-related artifacts, the stone foundation of the blacksmith shop, and other features of the blacksmith shop, including refuse disposal areas where many of the artifacts were found. The site was recorded as Millerstown 1 (36BL0124), named after the town that would grow up around the blacksmith shop.

So what did we learn from the archaeology of John Miller’s blacksmith shop? Some pretty surprising things, actually:

The historic record didn’t quite match the archaeological record.

Up until this point I’ve been calling John Miller a blacksmith, but that isn’t the whole truth. All historic accounts of John Miller actually call him a wagon maker. John Miller owned the property from 1823 until 1852 and archaeological investigations only found evidence of various types of blacksmithing – without any direct evidence of wagon making. Blacksmithing and wagon making are interrelated, but a wagon maker oftentimes worked alongside a blacksmith, not as a blacksmith themselves.

What is very clear from the historic record is that after John Miller sells his blacksmith shop in 1852, he moves to Bedford County to work alongside his eldest son, James. James Miller owns and operates a blacksmith shop beside his father’s wagon shop, and at least one historic account has them building a wagon for H.C. Lorenz, who managed the Rebecca Furnace and store (Adams 1948).

John Miller likely began his career as a blacksmith and the demands for his goods and services in the 1820s and 1830s would’ve been focused on edged tool production (e.g., axes/hatchets) and hardware for houses/barns (e.g., hinges, nails, hooks, latches). Then, as Millerstown grew and eventually multiple other blacksmiths came to town, John Miller may have begun to specialize in wagon making. The first historic record of him as a wagon maker isn’t until the 1850 census, 27 years after building his blacksmith shop.

John Miller had a coal-fired forge.

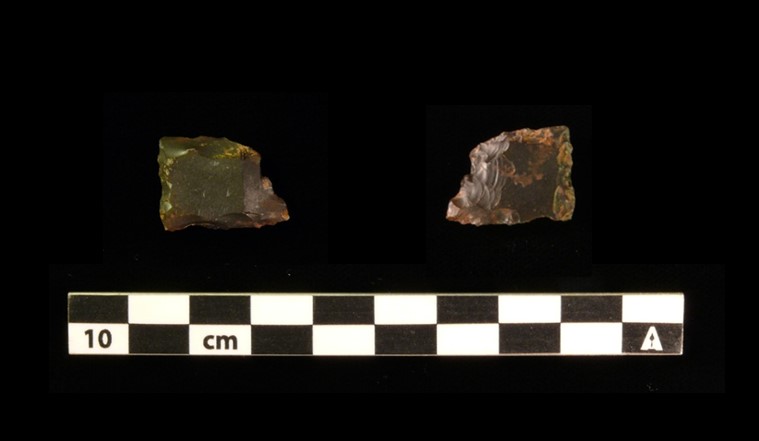

This one might be a bit obscure, but to a geology-minded archaeologist, it is a pretty revealing detail. In the 17th and 18th centuries, blacksmiths almost exclusively used charcoal to fuel their forges. However, by the late 18th century and early 19th century, some blacksmiths were starting to use locally available bituminous or anthracitic coal. However, the Juniata Valley is largely barren of coal, which is why the iron furnaces of the Juniata Valley relied on charcoal. The lone exception is the Broad Top coal field.

The Broad Top coal field, located about 7 miles southeast of John Miller’s blacksmith shop, is a small, isolated coal bed. This bituminous coal was discovered in 1765 by Nathan Port Horton, a blacksmith from northern Bedford County (DiCiccio 1993:26). Horton mined coal from surface outcrops of Broad Top coal to fuel his forge, benefiting from the unique characteristics of the coal. The Broad Top coal is one of the hottest burning coals in Pennsylvania and produces very little smoke, making it ideal for blacksmithing.

Collecting coal or charcoal, cleaning the forge, and lighting the forge fire in the morning are all jobs for the blacksmith apprentice. There is not any historic record of John Miller’s apprenticeship, but the use of a coal-fired forge at John Miller’s shop is good evidence that he did his apprenticeship training in northern Bedford County and learned about coal-fired forges.

Evidence of everyday life and individual smithing projects were preserved.

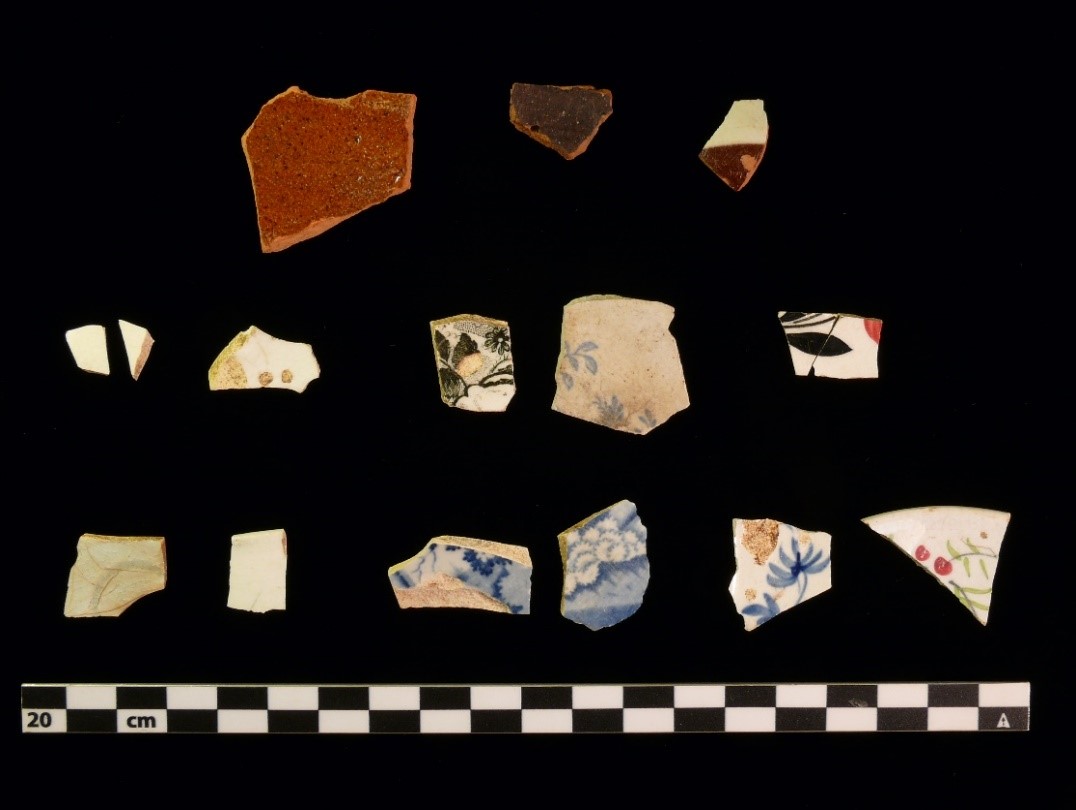

This is perhaps my favorite part of this archaeological site: the little snippets of what life in Millerstown was like in the first half of the 19th century. On the inside of the blacksmith shop, pushed up against the walls of the shop, fragments of broken ceramic plates/cups/dishes were found. Immediately outside the front door of the blacksmith shop, more broken ceramics and kaolin pipe fragments were found discarded in a midden.

Some of these artifacts are remnants of the blacksmiths going about their daily lives within the shop, but it is also evidence of the communal nature of blacksmith shops. As Karns noted in 1933: “the blacksmith shop is a favorite loafing place of some old-timers who have no special tasks confronting them.” In the 1820s and 1830s, prior to the construction of a church, store, or post office in Millerstown, John Miller’s blacksmith shop was the only ‘community’ space where people could gather and gossip.

Another artifact discarded in one of the middens by the front door is a well-used English gunflint, providing a glimpse of a project John Miller may have worked on. Replacing a gunflint certainly doesn’t require a blacksmith, though converting a flintlock rifle to a percussion cap rifle was a source of business for some blacksmiths.

Martin 1914 recalls: “In 1839, blacksmith John Fritz first saw a shotgun with percussion-cap-lock, changed his own old flint-lock, and soon had a monopoly throughout Chester County as a gunsmith.” Or perhaps someone’s flintlock just needed some repair.

John Miller’s blacksmith shop was short lived.

The historic record doesn’t indicate when the blacksmith shop was last occupied or when it was demolished. Deed and census data indicate it was never again owned by someone who identified as a blacksmith (or wagon maker) after Miller sells the shop in 1852. Most likely the shop was used by tenant blacksmiths for some years in the 1850s to perhaps the 1870s, though artifacts from the site all indicate the blacksmith shop was likely demolished by the late 1800s. John Miller continued working elsewhere as a wagonmaker into his 70s and three of his sons took up blacksmithing in Blair and Bedford Counties.

But John Miller’s blacksmith shop lives on.

The Millerstown 1 (36BL0124) blacksmith shop archaeological site was determined to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. PennDOT successfully redesigned their bridge replacement in 2017 to avoid the archaeological site and it remains preserved in place beneath that strawberry garden.

Want to learn more?

Before I could interpret the artifacts and cultural features that we uncovered in the field, I needed to first understand the intricate workings of a 19th century blacksmith shop. Thankfully many archaeologists have already trodden this path – most notably John D. Light who has written seminal articles like “The Archeological Investigation of Blacksmith Shops” and “A Dictionary of Blacksmithing Terms.”

And as archaeologists we are also fortunate to be in the company of so many others who were and are innately interested in the life and work of blacksmiths. Blacksmiths and blacksmith shops were frequently photographed at the turn of the 20th century, providing an excellent sample of how the interior layout of a blacksmith shops varied.

Perhaps even more helpful, many blacksmiths continue to practice the craft using methods past down for generations and have eagerly shared their knowledge with archaeologists. Many blacksmith shops have also remained standing or rebuilt as replicas at many historic sites and museums. So please, explore your local historic sites and museums!

References

Adams, David M.

1948 Historical Summary of Southern Morrisons Cove Towns. News Printing Company, Roaring Spring, PA.

DiCiccio, Carmen

1993 Coal and Coke in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Geil, Samuel and Isaac Freed

1859 Map of Blair County, Pennsylvania. Geil & Freed, Philadelphia, PA.

Karns, Reverend C.W.

1933 Historical Sketches of Morrisons Cove. Altoona Mirror, Altoona, PA.

Light, John D.

1984 The Archaeological Investigation of Blacksmith Shops. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology 10(1):55-68.

1987 Blacksmithing Technology and Forge Construction. Technology and Culture 28(3):658-665.

2007 A Dictionary of Blacksmithing Terms. Historical Archaeology 41(2):84-157.

Martin, Thomas C.

1914 John Fritz, Iron-Master. In The Penn Germania Vol. III pp. 202-208.

Great story here is some pictures of my wife`s great grandfathers shop in Waterford, Pa

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.734279569945705.1073741915.268770283163305&type=1&epik=dj0yJnU9RnF5eWV6X29ScWlmQ1RZVTl1bGhVWmc1ZVQwc21pMmsmcD0wJm49clpjY19YX3hCX2tmb3JGVlBqN1FTQSZ0PUFBQUFBR0tnd0Jr

Very interesting article! However, I believe Blair county is incorrect as the location. Millerstown, PA, is located in Perry county, along the Juniata river. It is indeed located near early iron deposits, in the Juniata valley, and along a main highway, just not in Blair county