The search for Thompson’s Island ends… and a new search begins…

Previously, I explained that archaeologist Chris Espenshade identified three likely locations for the Battle of Thompson’s Island—let’s call them Alternatives 1, 2, and 3— and ranked them based on how well they fit the historic record. Chris used a method called KOCOA (pronounced CO-CO-AH) military terrain analysis to identify and rank these locations. KOCOA looks at landscape from a military perspective, focusing on Key terrain, Obstacles, Cover and concealment, Observation and fields of fire, and Avenues of approach and retreat.

The southern tip of Thompson’s Island. Photograph by Kirk Johnson.

The Alternatives

Chris used the historical accounts to identify the above features that the battlefield should have and then looked for locations on the landscape where the features were present; the locations were ranked from best fit (Alternative 1) to worst fit (Alternative 3). The accounts and the analysis told him a couple of key things: that the battlefield would have been at most approximately 5 miles south of Brokenstraw Creek, that the battlefield would have been near an island, that the Native Americans would have escaped around the southern end of the island, that the battlefield would have been large enough for Brodhead’s advance guard to deploy in a specific formation, and that the battlefield would have been large enough for Brodhead’s total force of 600 men to encamp for the night. There are other criteria, but we don’t want anyone finding the site and looting it, so we’ll leave it at that.

Sample of Non-Battle Items Recovered from Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

With the three alternatives identified, he started with some archaeological metal detecting. Alternative 1 produced a lot of metal (most of it modern), but nothing definitively battle-related, which, though disappointing, is not surprising considering the short duration of the battle, the small number of combatants, and the amount of post-battle disturbance that this alternative has seen. Three of the finds, however, could date to the time of the battle: part of a horseshoe, a buckle, a pipe stem, and a brass spoon.

Horseshoe Fragment Recovered from Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

Buckle Recovered from Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

Pipestem Recovered from Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

Brass Spoon Bowl Recovered from Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

With nothing definitive at Alternative 1, Chris and his crew moved on to Alternative 2, which produced only a horseshoe which might or might not date to the battle . With nothing definitive from either of the first two alternatives, Chris and his crew visited Alternative 3; however, the topography and location did not fit the KOCOA analysis and it was removed from consideration.

Horseshoe Recovered from Alternative 2. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

Where does that leave us, you ask?

Even though we found nothing definitive archaeologically, we are still confident that Alternative 1 is the location of the battlefield: it fits the records, it fits the KOCOA analysis, and it fits what the Seneca would have looked for in a canoe landing spot.

Seneca Assisting in the Metal Detector Survey of Alternative 1. Photograph by Chris Espenshade (formerly of Commonwealth Heritage Group), 2015.

Also, when Chris Espenshade presented his findings at the Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology meeting in April 2016, retired Carnegie Museum archaeologist Dr. Stanley Lantz informed him that an amateur metal detectorist who wished to remain anonymous—metal detecting on federal land without a permit is a crime, so it is not surprising that this informant did not want to be identified— had found a .44 caliber musketball on Federal land very close to Alternative 1. This ball is in keeping with the caliber (.45-.50) of rifles of the time—Brodhead’s expedition did include riflemen—but it cannot be tied directly to the battle. If the provenance is correct, however, it lends circumstantial support to Alternative 1 being correct. Reports for the project, one redacted (for the public), and one unredacted (for professional archaeologists), are available at the State Historic Preservation Office—the abstract is available here—along with an Interpretive Design Concept Plan, one redacted and one unredacted – the abstract is available here–to guide future interpretive efforts.

So, I guess the project is over, right? Not so fast!

The background research indicates that Thompson’s Island may not have been the only battle associated with Brodhead’s expedition. You see, for many years study of the battle relied exclusively on Brodhead’s account of the expedition (a two-page letter to General Washington) and newspaper accounts that presented only the American side of the story.

When historians, including Eber Russell in 1930 and Merle Deardorff in 1941, consulted Seneca oral history, they found that it was likely that at least one other battle, which included American casualties, occurred north of Thompson’s Island—Brodhead had a powerful incentive to not report this since he had lobbied Washington extensively to undertake this expedition and wanted to present it in the most positive light.

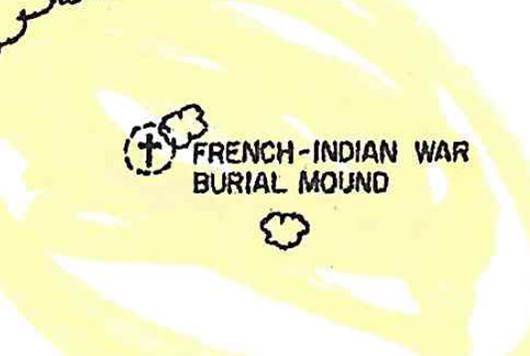

Oral history indicated that the Seneca town of Jenuchshadego (near the mouth of Cornplanter Run under the current Allegheny Reservoir in Pennsylvania) was occupied when Brodhead arrived; this information is supported by physical evidence in the form of one 3-inch shot that was recovered there. Furthermore, Seneca oral history indicated that Brodhead’s men faced significant resistance near present-day Salamanca and that several of his men were killed; this information is supported by the discovery of burials with muskets. In fact, a 1960s map uncovered by the Seneca Tribal Archaeologist further supports this story.

Detail of the 1960s Map Showing the Location of Burials.

Source: Army Corps of Engineers.

The map references the burials as being from the French and Indian War, but we know there were no French and Indian War battles anywhere near this location—the only likely candidate is a battle associated with the Brodhead expedition. Based on this information, the Seneca applied for and received an American Battlefield Protection Program grant to investigate this likely battlefield using both Seneca oral history and archaeological survey. The campaign continues; we will do our best to update you on this exciting project by the Seneca Nation.

Leave a Reply