What better time of year than National Historic Preservation Month to announce the latest round of PA SHPO’s Community Initiative Award winners! The four recipients and their projects showcase a range of preservation success stories, demonstrating the value of volunteers, creativity, and community engagement.

Category: Coal and Coke

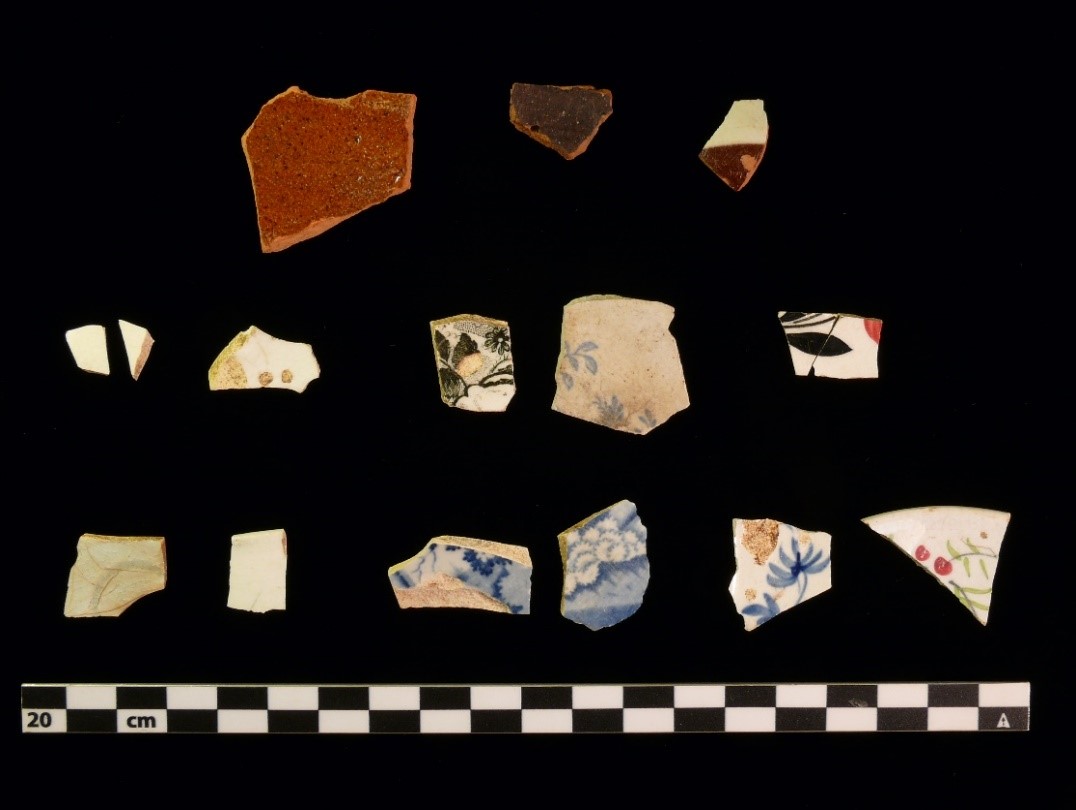

The Archaeology of a Village Blacksmith Shop

In 1823, a blacksmith named John W. Miller moved into what is now southeastern Blair County with his wife, Mary, and their three-year-old son, James. In their first years there they built their house and a small blacksmith shop along an existing road between Bedford and Rebecca Furnace. They didn’t have neighbors in those early years, but that wouldn’t last long.

Continue reading

Mine Sealing: A Little-Known Legacy of the New Deal

With Earth Day right around the corner, I thought it would be the perfect opportunity to share with you one of the little-known and fascinating historic contexts available from the PA SHPO: Mine Sealing in Southwestern Pennsylvania During the Great Depression. This may sound like a very narrow and esoteric context (and not even remotely related to preservation) but the story it tells is a timeless one that helps us understand the history – and balancing act – between the environment and industrial progress in Pennsylvania.

What is Mine Sealing?

Mine sealing is the act of closing an abandoned mine shaft to prevent acid mine drainage – acidic water – from contaminating surrounding streams and waterways. Any time you dig into the ground to mine coal you expose that coal to oxygen from the air and to water. These elements oxidize naturally occurring metal sulfides in the coal, creating water laced with sulfuric acid. When it drains from the mines, this acidic water can make its way into nearby waterways. This phenomenon is referred to as Acid Mine Drainage or AMD. Mine sealing began in earnest in the 1920s by the U.S. Bureau of Mines.

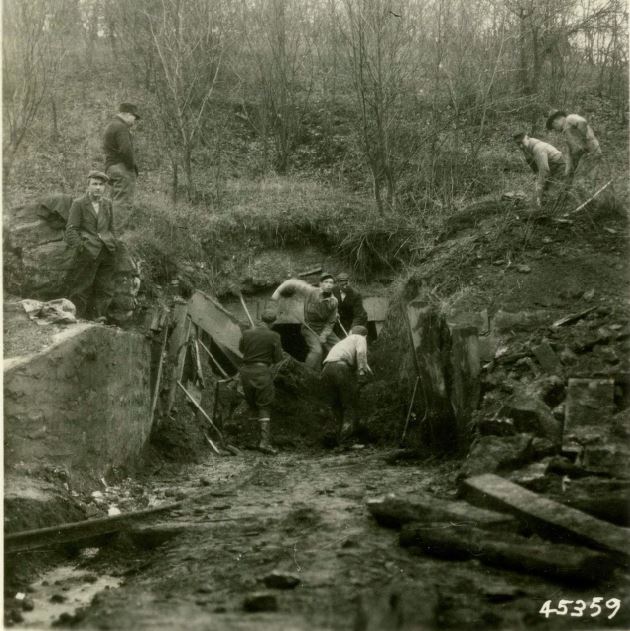

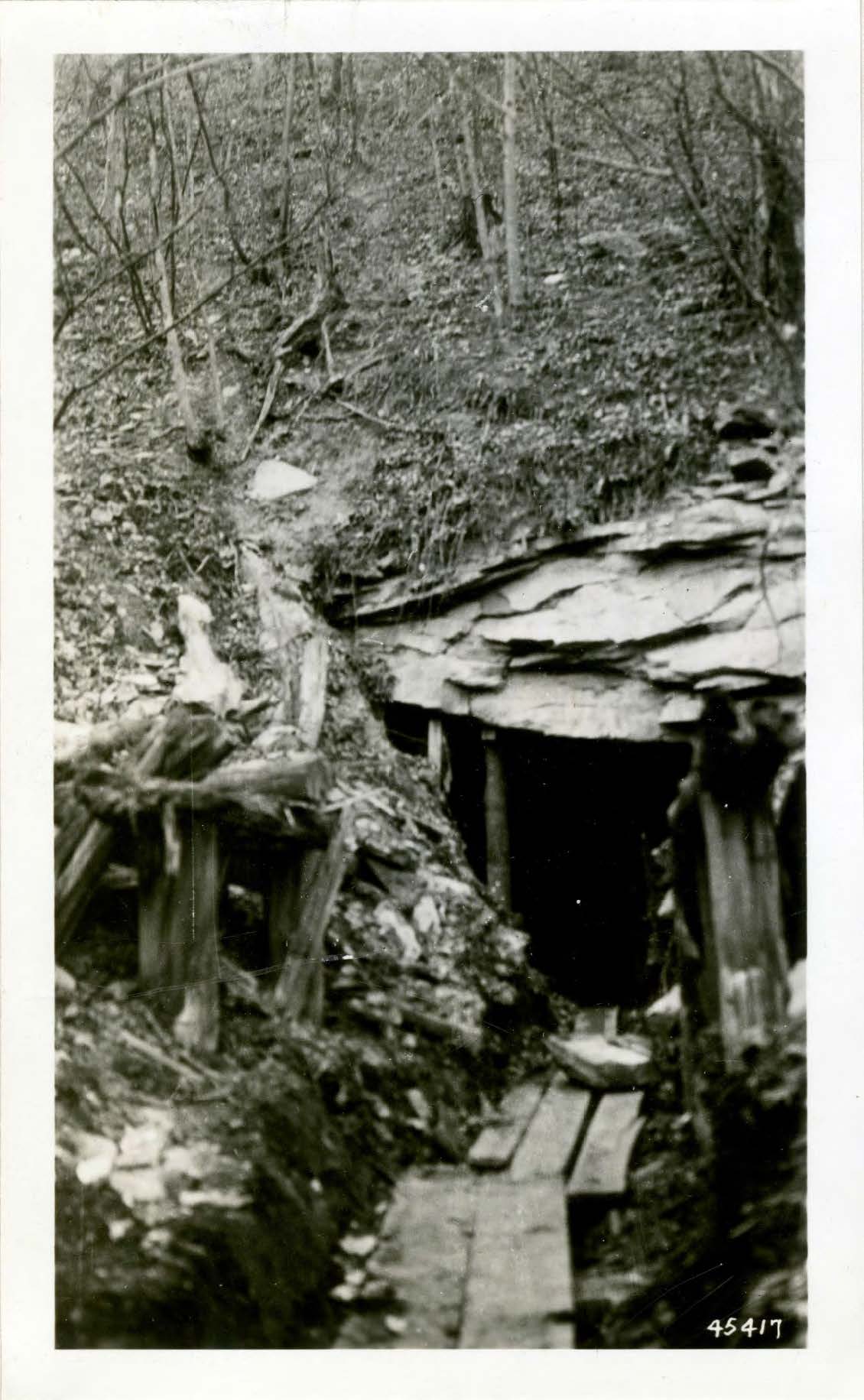

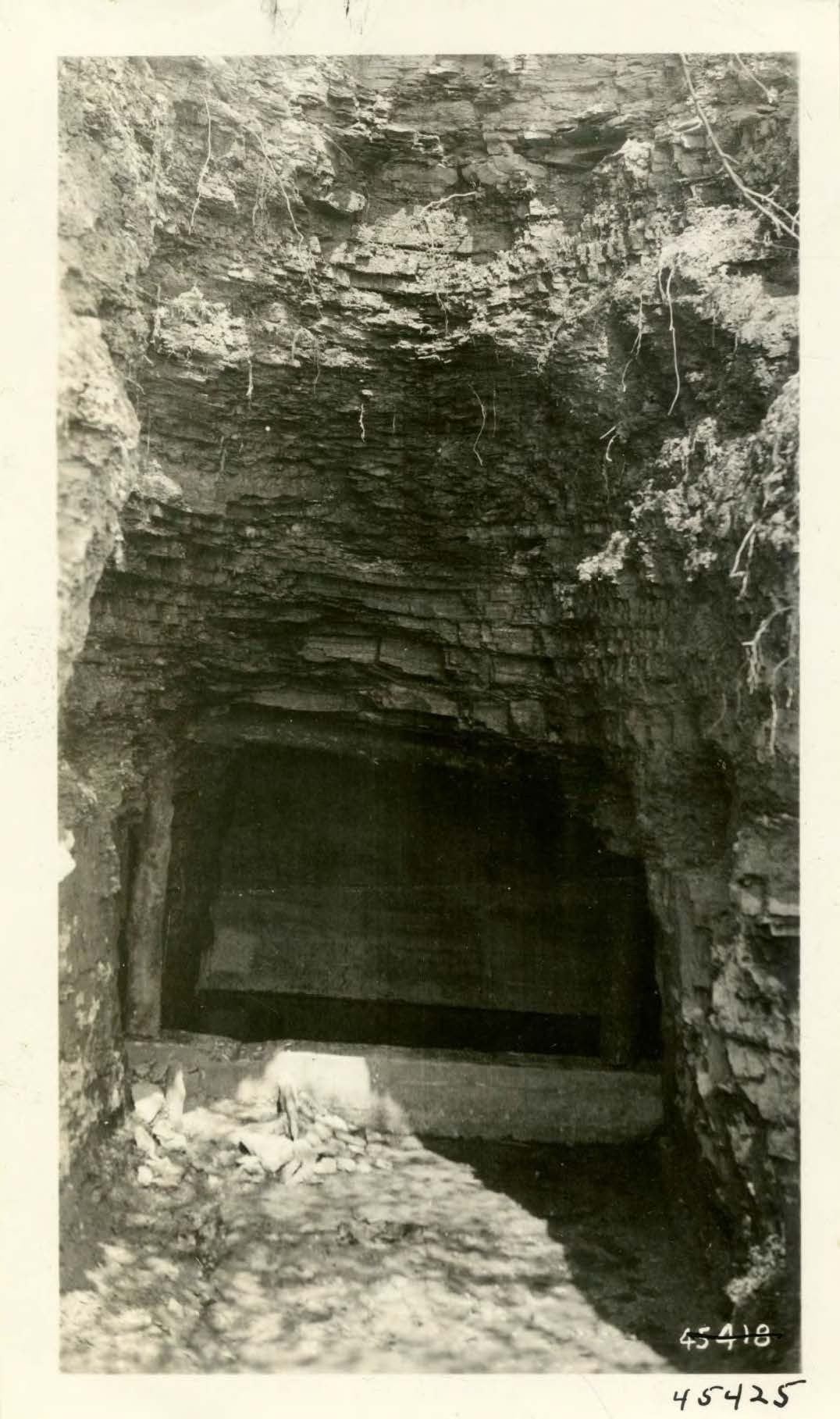

Typical Drift Mine Opening Prior to Sealing [Paul, James W. Report on the Sealing of Abandoned Coal Mines in Pennsylvania under Federal C.W.A. Project, State C.W.A. Project, and R.W.D. (S.E.R.B.). 1934. Typescript. C.W.A., Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania].

Pennsylvania’s Industrial Past

Pennsylvania has a fascinating industrial past. From agriculture to the extractive industries to steel production, Pennsylvania’s fortunes have been built – and lost – through industrial initiative and progress.

One of the state’s most enduring industrial legacies is that of coal mining. There are hundreds of essays and books about mining in Pennsylvania, which is divided into two regions: the anthracite coal region in northeastern PA and the bituminous coal region in southwestern PA. The PA SHPO has several historic contexts about industry in general and few about coal and coke specifically:

- 1989-H001-042 – A Legacy of Coal: The Coal Company Towns of Southwestern Pennsylvania

- 1997-M001-042 – Anthracite-Related Resources of Northeastern Pennsylvania, 1769-1945

- 1993-M001-042 – Bituminous Coal and Coke Resources of Pennsylvania, 1740-1945

One area these historic context studies didn’t cover much was the aftermath of mining activities. Enter the mine sealing context in 2013.

The Path to Mine Sealing

As coal mining took off in Pennsylvania in the 19th century, many citizens began to notice the effects of AMD. For example, in 1874, in the northeastern part of the state, J. Gardner Sanderson sued the Pennsylvania Coal Company for polluting a stream that ran through his property. The case was dismissed by judge W.H. Stanton who found that the company did not act maliciously and, although the complainant suffered damage, it was not of a type that would allow him to seek redress through the courts.

After winding its way through the courts for several years, the case ended with an 1887 Pennsylvania State Supreme Court Decision that stated that the property owner’s “…use and enjoyment of a stream of pure water…must ex necessitate give way to the interests of the community, in order to permit the development of the natural resources of the country and to make possible the prosecution of the lawful business of mining coal.” In other words, coal mining was in the interest of the community and outweighed the pollution of the homeowner’s stream.

In southwestern Pennsylvania, there were similar concerns, but with a slightly different focus. Concerned about AMD’s impact on the sport fishing community, in early 1875, state senator from Allegheny County, George Anderson, put forth a bill, “forbidding the pollution of streams, etc. by anything injurious to fish….” The bill did not pass the Senate, but the concept became part of state game laws passed later in 1875. A minor fine of $50 was imposed on those polluting the waters. A few months later in May 1876, the senate amended the law, making whoever reported the pollution responsible for the court costs.

A Two-Wall Concrete Trap at Risher Mine (Paul 1934).

It wasn’t until AMD began to affect another large Pennsylvania corporation, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), which needed clean water for the boilers of their steam engines, that things began to change. The PRR sued several coal companies and individual mining operators in Fayette County Court in 1921, but the judge found in favor of the mining operators. The PRR appealed the case to the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court, who reversed the lower court decision and ordered the mining operators to stop discharging acidic water into streams. The mining operators appealed this decision to the United States Supreme Court, which refused to hear the case, leaving the Pennsylvania State Supreme Court decision in place.

Addressing AMD

With this decision, the mining industry had to find a way of addressing AMD. The preferred method, advanced by the U.S. Bureau of Mines and others in the 1920s, was sealing the abandoned mines. Mine sealing could be as simple as caving in the mine entrance or as complex as creating an air or water lock to prevent the acidic water from leaving the mine. With so many abandoned mines to seal, the issue became how to pay for a large-scale mine-sealing program.

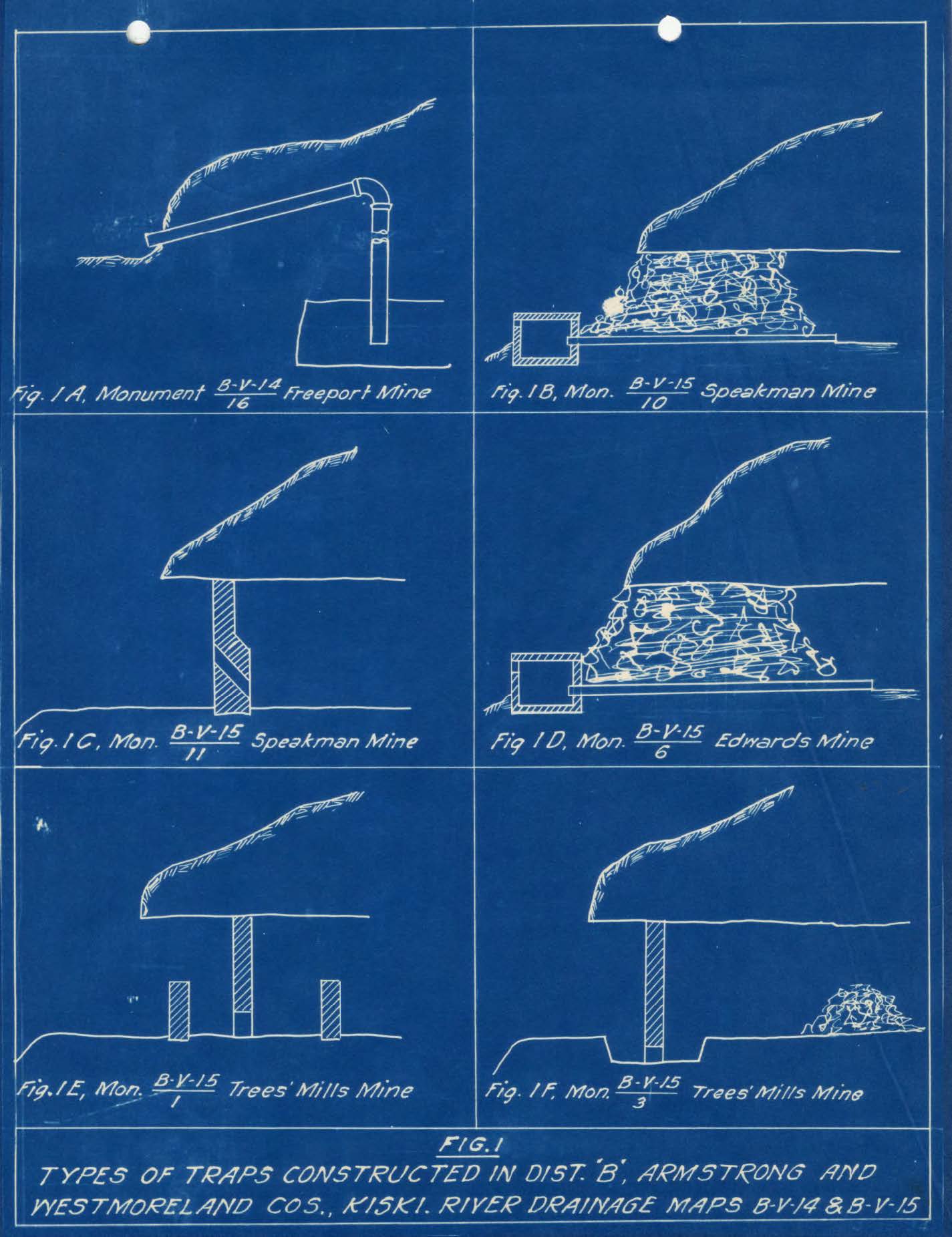

Types of Mine Seals Constructed in Armstrong and Westmoreland Counties (Paul 1934).

With the coming of the Great Depression and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal federal relief programs, funding became available. In Pennsylvania, and several other coal-mining states, the mine sealing program, first under the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and then under the Civil Works Administration (CWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA), sealed thousands of abandoned mines as public works projects. Working together, state and federal officials and mining engineers developed a methodology of water testing and public health risks to identify which mines needed to be sealed. At the program’s height, mine engineers had six different basic designs for mine seals that could be adapted for each sealing situation. One study highlighted in the historic context states that in Pennsylvania alone, work crews in the 1930s sealed 30,000 openings at 317 mines in 22 counties.

A Mine Seal Today, East Huntingdon Township, Westmoreland County (Photo courtesy of AECOM).

Mine Sealing’s Legacy

Unfortunately, the mine sealing activities under the state and federal program did not provide a permanent solution to AMD, meaning that mines continue to be sealed and re-sealed today. In Pennsylvania, the Department of Mine Safety oversees these activities. The mine seal discovered in Westmoreland County is unlikely to be the last and, as more are discovered, the mine sealing historic context is a great place to get a better understanding of the role these seemingly innocuous places in our natural environment.

Recent Comments