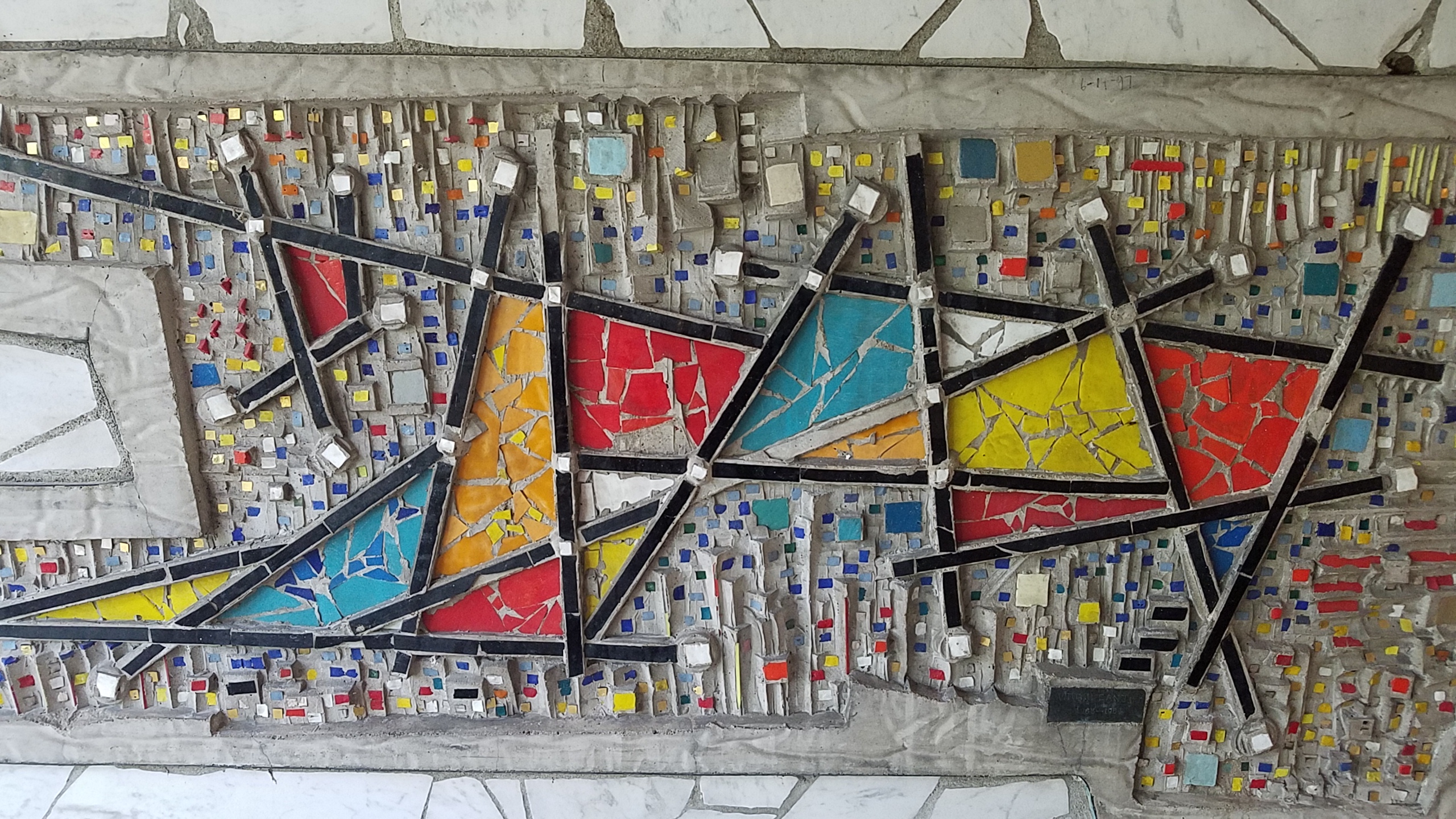

Last week’s blog post introduced the life and work of artist Virgil Cantini and highlighted the vulnerable position of postwar public art objects and installations, which often require special expertise to understand and articulate their significance for preservation.

This week’s post recounts part of the struggle to save one of Cantini’s largest works of public art, which came dangerously close to disappearing forever.

Continue reading

Recent Comments