If historic preservationists could choose a superpower, it just might be the ability to move buildings to a new location when they are threatened with a proposed demolition.

Unfortunately, moving a building is not always possible, rarely practical, and always expensive. But what if there was a building type that was actually built to be moved and that essential characteristic could be the key to their survival?

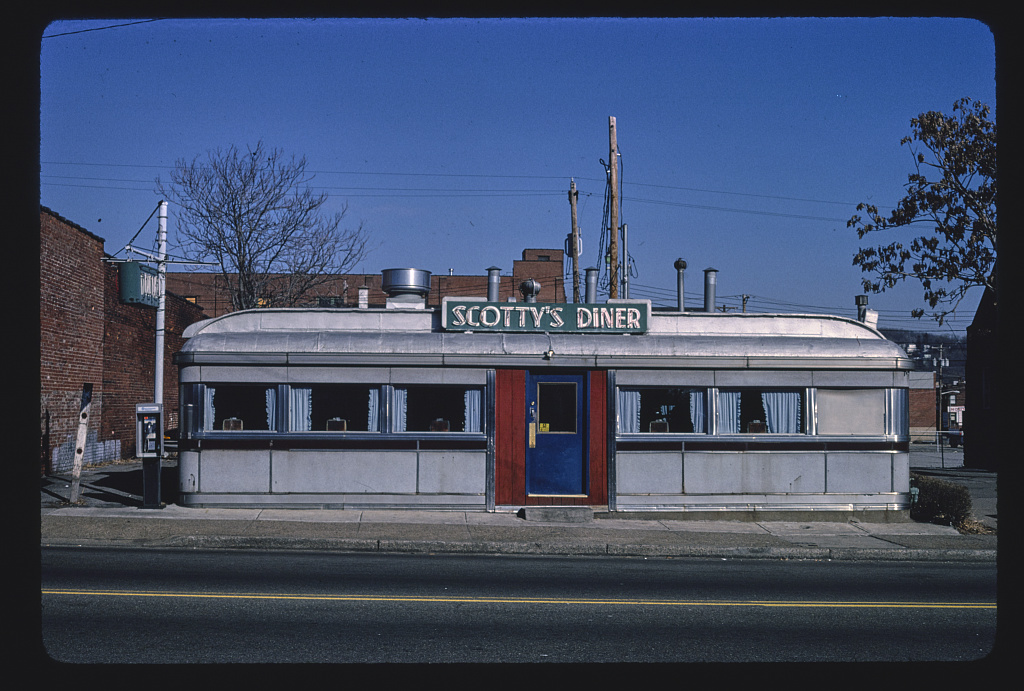

What building type is made to move and sometimes even has wheels? The Diner!

(Very) Quick Diner History

The diner is in many ways an American invention, designed for quick and easy construction (or moving), low maintenance, and efficient service.

The diners we know and love today can be traced to late 19th century mobile food carts in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. These gave way to stationary food carts, which gave way to the prefabricated diners that could be found throughout much of the eastern and mid-western United States by the mid-20th century, thanks to Americans fascination with the automobile.

Many of Pennsylvania’s diners were constructed in New Jersey by companies like Fodero in Bloomfield, Mountain View in Singac, Jerry O’Mahony in Elizabeth, or Silk City in Paterson, and then have been moved once or even more than once over their lifetimes.

If you’re learning more about the history of diners, check out “A Life Devoted to the American Diner” by Smithsonian Magazine.

So, what makes a Diner, a Diner?

I think we could all agree that is the sleek, mid-20th century materials, linear design, small(ish) scale, and, in some cases, its move-ability. We typically refer to this collection of characteristics as “historic fabric” and “character-defining features”.

Integrity is the word architectural historians use to evaluate how much historic fabric is left of a building and how much a building has changed over time. But don’t confuse the condition of a building with its integrity! Condition is the level of deterioration of the building materials, whether they are old or new, while integrity is how much of the historic fabric of the building remains.

In other words, would that building be recognizable to someone who was familiar with it during the period of time in which it was significant? Or have the character defining features and building’s materials been altered in a way that is unsympathetic to the historic building and is un-reversable?

Integrity of Materials, Design, and Workmanship

Early diner forms of the 1920s and 1930s, which evolved from the design of lunch cars or railroad dining cars, would have a painted steel or porcelain exterior, operable windows, a characteristic barrel roof, counter seating with stools, and an internally integrated open kitchen often visible to the patrons.

These early diners, would be completely self-contained restaurants transported by railroad, trucks, or by barge, and sometimes may have even had wheels to help roll them into place. They could be tucked into a vacant lot in a dense downtown or they could be placed on the side of a highway.

The Ace Diner claims to have been in the same location since the 1937.

The interior of the diner still serves customers at its Formica counters and stainless steel stools or in vinyl upholstered booths with attached chrome coat racks.

But the roadside diner building is hiding in plain sight! Over the years, the exterior has been mostly covered with a later cladding material. Without removing the later alterations to reveal the original diner underneath, it would not be eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

By the mid-1930s, diner buildings began to reflect the automobile age with their streamlined style and gleaming stainless steel cladding, often patterned, with rounded corners, large fixed plate-glass windows and a central entry vestibule.

This era of diner design and construction was modular by manufacturing portions of the diner buildings which would be transported separately and then assembled on site this allowed diner buildings to become much larger than they had previously been.

In addition to counter service, their increased size allowed them to begin to incorporate booths and tables, often with characteristic and functional elements like coat racks and wall clocks added new features like built in restrooms, phone booths and possibly neon signage.

Here you can see that Bob’s Diner retains a high level of integrity including its signature decorative clock centered above the entry vestibule, a common character defining feature of stainless steel diners which is often lost to changes over time.

Integrity of Location and Setting

Whether we are taking about early diner cars, originally modeled on the fine dining cars of railroads, or a later pre-fabricated stainless steel diners designed as a modular system and built in pieces to be assembled on site, a diner is a factory-built restaurant designed to be moved.

Ordinarily, a property that has been moved will render it no longer eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, according to the National Park Service’s Criteria for National Register eligibility. However, the National Register’s criteria for eligibility have seven Criteria Considerations for special circumstances under which there are exceptions to the ordinary rules.

Criteria Consideration B addresses moved properties and outlines the circumstances under which a property can remain eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, even if it has been moved to a new location.

According to the National Park Service “a property removed from its original or historically significant location can be eligible if it is significant primarily for architectural value”, “a moved property significant under Criterion C must retain enough historic features to convey its architectural values and retain integrity of design, materials, workmanship feeling and association” and “must still have an orientation, setting and general environment that are comparable to those of the historic location and that are compatible with the property’s significance”.

So, in order to remain eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a diner, as an architecturally significant building type, would need to be moved to a compatible setting AND retain its integrity after it is moved.

Share Your Diner Love

One of the challenges of historic diners is keeping up to date with architectural survey of buildings designed to be on the move.

Believe it or not, there are only a handful of Pennsylvania’s diners in CRGIS and only one listed in the National Register of Historic Places – the Park Dinor in Erie (Key #119352).

If there is a diner like I’ve talked about here in your community, let us know about it by leaving a comment or emailing me at jensolomon@pa.gov.

Learn more about historic diners

If you would like to read more about the history of diners and find Pennsylvania’s gems, you can grab a copy of the Diners of Pennsylvania (2011) from your local bookshop or library.

If you would like to read more about the history of diners and how to identify them by sub-type, both Massachusetts and Virginia have prepared Multiple Property Documentation Forms (MPDF) in order to assist in the evaluation of the building type. They can be found here:

Massachusetts: https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/64500250_text

Virginia: https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/151-5508/

These contexts have heavily relied on the substantial scholarship and writing of Richard J.S. Gutman, a native of Allentown, Pennsylvania, and his definitive book American Diner, Then & Now, which he wrote in 1993 and was republished in 2000.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.