A long, long time ago (okay it was only 2014, but still…) I wrote about local preservation in Pennsylvania and at the end of that article I promised a follow up with some additional insights. Time passed and lots of other interesting projects and places were more worthy of being featured on this blog. But, a promise made is a promise kept, so here’s the second installment of the “3 things to know” series. This time we’ll focus on one of the more commonly confusing issues in preservation – the differences between the National Register of Historic Places and local historic designation.

1. The National Register and local registers are not the same

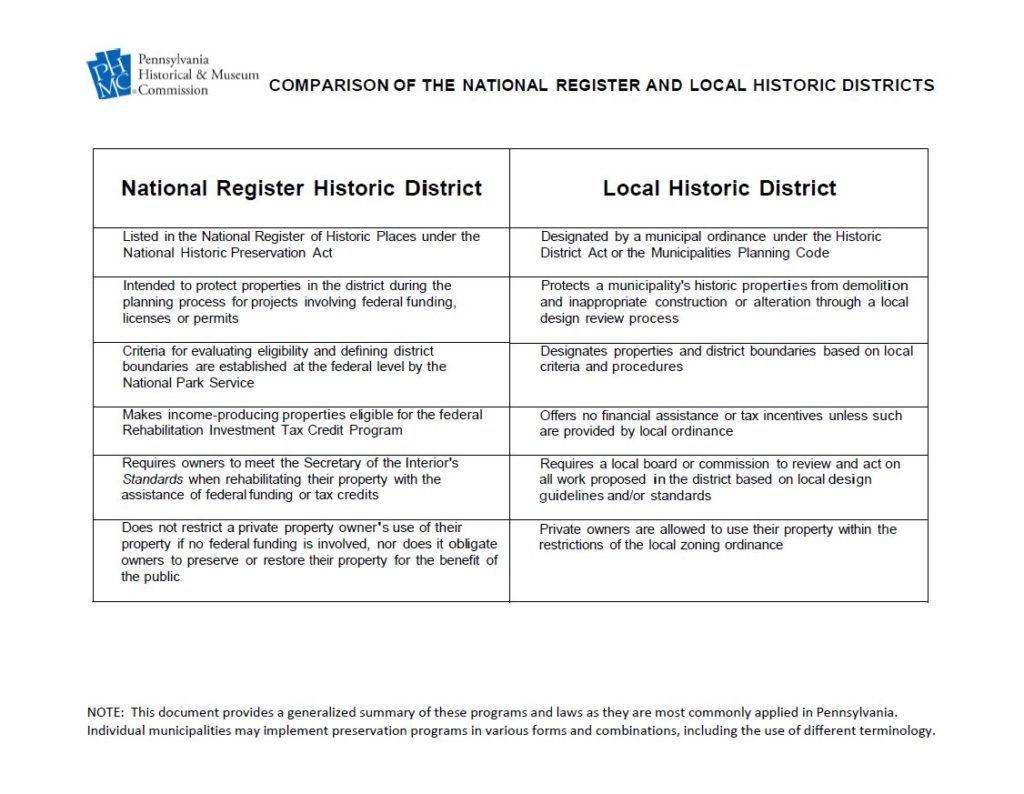

This may seem like an obvious point, but it’s an important piece of background information. The National Register of Historic Places was established by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) and is “the official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation.” That’s a pretty bold statement and a hefty burden for the list to shoulder. And while the National Register status of a property is employed in a variety of ways across various funding and regulatory programs, it’s important to keep in mind some of the history behind its creation. The NHPA was passed at a time when Federal agencies were building massive highways, housing projects, and other public works projects that impacted many of our nation’s oldest communities, but without a mandate to consider whether any of the buildings or archaeological resources affected by those projects had any enduring historical, architectural, or cultural value. The National Register was one way to identify, document, and evaluate properties and provide planners and agencies with information about significant places that should be taken into account during Federally-supported projects. Over time, National Register listing became a prerequisite for grant programs, the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Credit, façade easement donations, and other publicly-supported programs. In this way, the Register is fulfilling its mandate as “the official list of the Nation’s historic places worth of preservation” since the Federal government has prioritized listed places for financial and regulatory programs under its control.

Local registers, sometimes called inventories, are created by municipal preservation ordinances and typically have some form of review process or regulation associated with them (though not always). Like the National register, these lists are created to reflect a municipality’s priorities and include the properties they feel merit preservation, thus they apply the powers and incentives within their control to these inventories. Often times, local registers will include properties that are also listed in the National Register, but depending on the criteria used to add properties to a local list, there may be some places that are important locally that aren’t NR listed, and vice versa.

2. The National Register and local registers do different things

Again, perhaps this is stating the obvious, but building on the origins of these lists described above, it’s important to note that these mechanisms mean different things to different people/players. For example, listing in the National Register does not place any restrictions or requirements on private property owners. There are no approvals required for changes to NR listed properties that are paid for with private money and don’t require Federal or State permits or licenses. But there are also no protections, meaning that NR listed properties are occasionally demolished or insensitively altered with no opportunity for those plans to be reviewed or even stopped. Thus, for most property owners, NR listing is largely a badge of honor or an opportunity to take advantage of financial incentives.

The only time the National Register status of a property triggers a review process is when a project involves State or Federal money, licenses or permits. Examples might include a grant for a development project, bridge repair/replacement, a permit for wetlands, a license for a cell phone tower, etc. In that case, a process called Section 106 is triggered (if it’s Federal involvement) or a Pennsylvania History Code review (if it’s State involvement), but those are subjects for another time…

Local registers, on the other hand, are usually associated with ordinances that require property owners, public and private, to obtain some sort of approval before undertaking certain types of projects, regardless of funding. Examples include installing a new roof, modifying the porch, or full scale demolition. The difference is that the local registers (and the ordinances that create them) are exercises of a municipality’s police power, just like building codes or zoning. If a property is listed in both the National and a local register, then the review and approvals that are required are a result of the local listing, not the National Register listing. Confused yet?

![The Society Hill Historic District in Philadelphia is listed in both the National Register of Historic Places and the Philadelphia Register. By Beyond My Ken (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://pahistoricpreservation.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/201-213_Delancey_Street_Society_Hill.jpg)

The Society Hill Historic District in Philadelphia is listed in both the National Register of Historic Places and the Philadelphia Register. By Beyond My Ken (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

3. The National Register and local registers can be the same – so long as they’re different

Are you seeing a theme here yet? Many communities with preservation ordinances want to use those tools to designate and protect properties that are listed on the National Register. This makes sense since the NR is supposed to be the list of places worthy of preservation, right? It also makes sense to utilize survey documentation for multiple purposes rather than reinventing the wheel. For a variety of policy, legal, and practical reasons, our office does not encourage or support using the National Register status of a property as a criteria for designating or classifying properties on a municipality’s local register. Instead, we recommend incorporating criteria that mirror the National Register criteria into the ordinance and then developing a process where a review board, historical commission, or some other body adopt findings as to how the properties meet those criteria, without reference to the National Register status. The ordinance can also have criteria that aren’t part of the National Register lexicon, such as language addressing viewsheds or recognizable community landmarks. The municipality would then use the conclusions drawn in the NR documentation to articulate its own conclusions about the significance of the property. This is more straightforward than it may seem at first and puts the community on firmer ground procedurally.

The Tacony-Disston Development Historic District in Philadelphia is listed in the National Register, but is not on the Philadelphia Register.

If you’re curious about what properties in your community are listed in the National Register, or other places the SHPO has survey documentation on, visit CRGIS, our online map and database to have a look. For assistance on local preservation issues or ordinances, contact your Community Preservation Coordinator for help.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.

Thanks Corey, great article and it couldn’t be more timely for Kennett Square. KSQ nearly lost its oldest timber framed industrial building due to Borough Council’s ignorance of the HARB process. Long story…during the demolition, the owners found that the building is not too far gone to save and are now hoping to re-purpose the old bone mill as a Kennett history center. They are seeking information on possible funding sources. Besides the Federal Rehabilitation Investment Tax Credit, are there any other programs they should be aware of?

Thanks Corey, the Monroe County Historical Association is managed from the historic Stroud Mansion in Stroudsburg PA, which is on the National Register of HP and within the Stroudsburg Historic District. We are currently planning to expand the footprint of our operation, for long overdue storage needs, by adding a substantial addition to the mansion house. Of course, we have been actively engaging with the community Hist Arch Review Board and have discussed this with your office. After a design competition we have selected our architectural design firm and expect to collaborate with your office to assure that we abide by Preservation Brief #14 in order to assure that the addition is sensitive and complementary to the historic mansion house but also distinct in its own construction and architectural statement in the community. Lots of moving parts in these early stages but we are determined to have the new mesh with the old in our community! Preservation is a challenge but rewarding in a small community like ours! Thanks for your help.

Great summary for us novices Cory.