September is International Underground Railroad Month. September was chosen because it is the month that two of the most well-known people associated with the Underground Railroad – Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass – escaped from slavery. Today’s post was written by guest author Dr. Leroy Hopkins and he provides a glimpse into the Underground Railroad in Columbia, Pennsylvania.

At the height of the pandemic, a group of scholars and public historians met via Zoom to discuss what would become a successful application to Governor Wolf to proclaim September as International Underground Railroad Month. Samuel W. Black of the Heinz History Center coordinated this effort under the auspices of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, similar to states across the country.

Why was this proclamation important? Pennsylvania was created by William Penn and his Quaker allies to be an oasis of tolerance in which all religious groups could worship without coercion or governmental interference. The commonwealth was also the arena for the most important civil rights struggle since the founding of the Republic: the fight to end slavery.

How we think and talk about the Underground Railroad (UGRR), in the commonwealth and throughout the country, has changed since the Civil War. The UGRR, and the people and places associated with it, have long been the subject of study and explored through academic papers, non-fiction and children’s books, articles, documentaries, and more. Slavery and the UGRR have also been romanticized in movies and novels, often incorrectly portraying Africans and African Americans as accepting and appreciating their enslavement, like in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind.

With two notable exceptions, that are mentioned below, the early history of the Underground Railroad was compiled by white historians. These accounts tended to focus their narratives on the white people and institutions who participated in the UGRR. The role of Blacks as either users or agents of the routes to freedom was often relegated to footnotes rather than the focus of the story.

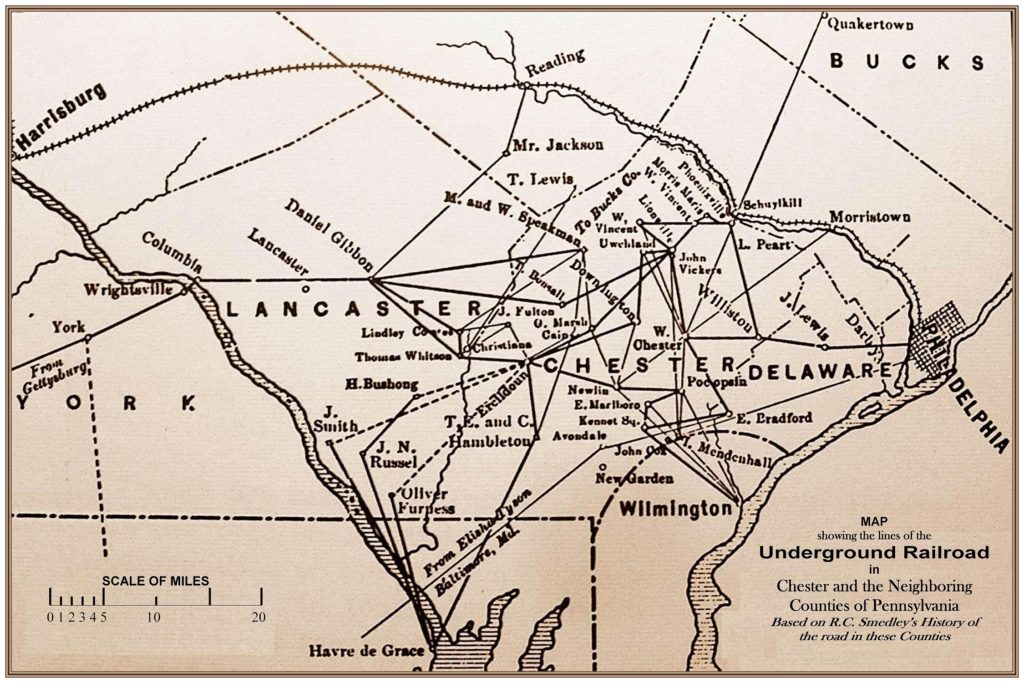

Robert C. Smedley, for example, interviewed members of the Society of Friends (Quakers) for his 1883 book, History of the Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania. But Smedley only mentions William Whipper and Stephen Smith, two leaders of Columbia’s Black community, in terms of to whom they passed freedom seekers. Wilbert H. Siebert, the Ohio State historian and author of the 1898 The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, sought out all possible sources and presented a more balanced and accurate history.

It was through this research that Siebert found Rev. Wiliam M. Mitchell’s The Underground Railroad (1860). Mitchell is introduced as a “gentleman of colour, who was born and reared in North Carolina, United States.” In his narrative, Mitchell recounts an origin story for the term “Underground Railroad” that corresponds to a similar anecdote told in our region.

Mitchell relates how a slave master in pursuit of his escaped property reached the Ohio River and lost track of his prey. The pursuer allegedly said that the abolitionists must have placed a railroad under the ground to help the enslaved Africans to escape. Instead of the Ohio River, locally the anecdote was told about the Susquehanna in Smedley’s account and referred to freedom seekers crossing the massive wooden covered bridge from York County and finding assistance and anonymity in Columbia Borough’s sizable Black population.

It can be challenging to point to a specific date for the creation of the Underground Railroad as a network of people, routes, and locations that assisted freedom seekers moving into states, territories, and countries that did not enslave Africans and African Americans.

Many cite the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act as the impetus although many enslaved people made their way out of the South on their own as well as through an informal network that existed long before it was organized and given a name. For example, in Lancaster County, Daniel Gibbons (1775-1853) reportedly continued work begun by his father James (1735-1810), while the Wright Family of Columbia is reported to have been active during the first decade of the 19th century.

Given the multiplicity of potential origin stories it is opportune to focus on our area, south central Pennsylvania and use the other source created by a Black participant to describe the workings of the Underground Railroad: William Still. Still (1821-1902) went to work for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1848 and, after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, chaired its vigilance committee.

In that capacity he not only assisted freedom seekers sent to him but also recorded their stories. This was quite dangerous since any record of his activity could have threatened both him and the individuals whom he helped either to stay in the Philadelphia area or to continue on to relative safety in Canada. In 1872, Still published his records and among the persons reporting on their activities is a letter from William Whipper (1804-1876), a native of Lancaster County’s Southern End and undoubtedly the best educated free African of the Antebellum Era.

Columbia was the most important point of entry for freedom seekers coming from Maryland and Virginia after the Chesapeake Bay was made impassable because of patrols. In Still’s history, Whipper is identified as the only UGRR station master who represents Columbia .

Whipper had only resided in Columbia since the late 1830’s when he traded places with his business partner Stephen Smith. Smith was an astoundingly successful merchant who rose from indentured servitude as a child to become the richest Black man east of the Mississippi. Ordained as a deacon in the A.M.E. Church, Smith created the firm of Smith & Whipper in 1841 and made the Philadelphia area his permanent residence. Smith’s success made him a target in a series of race riots in 1834.

In his 1871 letter to Still, William Whipper mentioned several options which he offered the freedom seekers who appeared at his door. Many chose to stay in work in prosperous Columbia despite the growing danger of recapture. Others he sent by canal boat to Pittsburgh or on his “cars” as he referred to his firm’s privately-owned railroad freight cars. He and Smith together with William Goodridge, their partner in York, owned almost two dozen railroad cars.

The locomotives were owned by the state’s Main Line of Public Works, while the engineers and other crew members were employees of the commonwealth. Private freight haulers or passenger line operators paid a fee to the state to attach their cars to the steam engines. In the case of Whipper and Smith, they fitted their cars with secret compartments behind a false interior wall. They are reported to have begun this activity in 1838, just four years after regular rail operations began.

This practice continued it until the state assumed total control over the railroad in the late 1850’s. There is no record of a freedom seeker being apprehended who was sent by Whipper by train to Philadelphia. Once control over the train was relinquished, Whipper partnered with George DeBaptiste (1815-1875) to buy a steamboat in 1859 that traveled between Detroit and Amherstburg, Ontario to ship lumber and freedom seekers.

All aspects of the Underground Railroad in south central Pennsylvania have yet to be fully researched and documented. It is significant that through networks such as churches, fraternal organizations, and the Colored Convention Movement from 1830-1860 that men and women throughout the commonwealth were able to meet, strategize, and implement plans to help freedom seekers who sought their assistance.

Today’s guest author is Dr. Leroy Hopkins. Dr. Hopkins is a retired German language professor and life-long resident of Lancaster, Lancaster County, PA. He has written extensively about African American heritage in journals, magazines and books and is currently serving as Historian with the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania. He has extensive experience working with state agencies and non profit groups to promote African American history in the commonwealth and has worked closely with PHMC in the past. He also tells me that he has a very personal interest in this work because of strong family connections to the Underground Railroad in Hartford County, MD and Havre de Grace, where he believes his 4th great grandfather Cupid Paca (or Peaco) was involved in the smuggling of freedom seekers up the Susquehanna to Williamsport and then Canada.

Randy Harris provided the archival images, as a member of the staff of LancasterHistory, focusing on research and community outreach for the Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History and Democracy. He is also a consulting historian based in Lancaster and is the former Archivist for the African American Historical Society of South Central Pennsylvania.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.