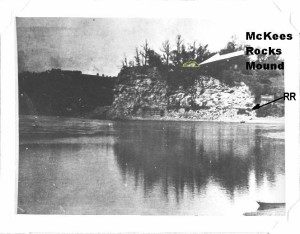

Location of McKees Rocks Mound on the bluff overlooking the mouth of Chartiers Creek with the Ohio River in the foreground. This photograph was taken in 1896 and is used courtesy of the Section of Anthropology of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. It was taken from either from a boat or Brunot’s Island in the Ohio River. The white arrow was added by the excavators. There is a train track at the base of the bluff. The author added the mound outline, dark arrow pointing to the railroad line and mound label.

McKees Rocks Mound was the largest prehistoric mound found in Western Pennsylvania. It was 16 feet high and had a basal diameter of 85 feet. The mound was well known in the 19th century and was located on a bluff overlooking where Chartiers Creek enters the Ohio River in the borough of McKees Rocks.

McKees Rocks Mound prior to excavation in 1896. Photograph is courtesy of the Section of Anthropology of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

McKees Rocks Mound attracted the attention of the newly formed Carnegie Museum of Natural History and became the first site excavated by that museum in 1896 under the direction of Frank M. Gerrodette (Note: this is the correct spelling, Swauger reference below only uses one “r” in the name). Gerrodette only excavated one half of McKees Rocks Mound in 1896. He determined that the mound was built over time in three separate mound building episodes. His work was prior to the development of the local prehistoric chronology and Gerrodette could only generally describe what was found. It also was before the development of radiocarbon dating which would have provided more precise dates for the various mound construction episodes.

McKees Rocks Mound during the 1896 excavation by Gerrodette. Photograph is courtesy of the Section of Anthropology of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Examination of the materials recovered by Gerrodette by later archaeologists (see references at the end of the blog) determined the first two periods of mound building occurred during the Early Woodland period (500 B.C. to A.D. 100) by people who have been have been called Adena or Cresap phase Adena groups. The mound was about 15 feet tall after these two building episodes. The last or most recent period of mound building was assigned to the Middle Woodland period (A.D. 100-1000) because pottery with limestone temper typical of this period was recovered.

Gorgets placed with the important Early Woodland burials at McKees Rocks Mound. The bottom gorget was placed with the central burial in the earliest portion of the mound; while the upper gorget was placed with the central burial in the second mound stage. Photograph by the author. Collection access courtesy of the Section of Anthropology of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Only one burial was found in the earliest section of McKees Rocks Mound, and it was assigned to the Early Woodland period. This burial had a gorget (an item believed to be hung around the neck that may indicate some type of rank or high position in its society), a grooved adze, one copper imitation bear canine with a piece of twined fabric adhering to it, 357 columnella shell beads made from portions of central columns from welk shells and 153 marginella (a small snail) shell beads placed with it. The copper bear canine likely was made from a native copper nugget from the Kennesaw area of Wisconsin or the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It may have been obtain in trade with other groups or from someone actually traveling to that area to get the copper. The fabric adhering to it may have been from a bag that contained the imitation canine. Similarly, the welk shells likely were obtained at the Atlantic shore either through trade or travel. Several other items made of local cherts or bone also were recovered.

Imitation bear canine with twined fabric adhering to it that was found with the central burial from the earliest section of the mound. Photograph by the author. Collection access courtesy of the Section of Anthropology of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The younger or uppermost of the two Early Woodland portions of the mound contained two burials; one of which was considered to be the main burial for that construction episode. This burial also had a gorget placed with it. No artifacts were associated with the second burial. Other artifacts were found in the fill of the second mound building episode. However, they were not with the burials and accidently may have made it into the mound when the builders dug up dirt from an earlier site to use in covering the burials.

Thirty burials were found in the last portion of the mound that added the final covering bringing the height of the mound to 16 feet. One of these burials had some pearl beads from local fresh water clams. Three burials had pot fragments tempered allegedly with limestone that were considered Middle Woodland pottery types.

The author became interested in the materials from McKees Rock Mound when he was working on a summary of Early Woodland materials from Western Pennsylvania in the 1990s. The collections were examined at that time in the Section of Anthropology of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. It was found that the pottery associated with burials from the latest mound building episode was actually tempered with shell, not limestone. Shell tempered pottery is characteristic of the Late Woodland or Late Prehistoric period (roughly A.D. 1000-1550/European Contact) and not the Middle Woodland.

On May 18, 2002 a Pennsylvania Historical Marker was dedicated in a park at the base of the bluff where McKees Rocks Mound was located. Text of the marker reads, “Largest Native American burial mound in Western PA., (16 ft. high & 85 ft wide). It was hand-built by the Adena people between 200BC and 100 AD and later used by the Hopewell and Monongahela people. Late 19th C. excavations uncovered 33 skeletons and artifacts made of copper & shells.” The date for the Adena is only for a portion of the time when they may have influence people in Western Pennsylvania. We now know the earliest dates for mounds in this region go back to almost 500 B.C. Also, there is little good data indicating a Middle Woodland Hopewell influence on the burials at McKees Rocks Mound.

After the marker was dedicated the Seneca tribe became involved with trying to located and insure preservation of the half of the mound that was not excavated by Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 1896. The author became involved in this search in 2008. A group of Seneca and the author visited the bluff on August 8, 2008. It became clear that the bluff had been modified at sometime after the excavations by Carnegie. The bluff had been quarried for rock that was later crushed and allegedly used as aggregate for macadam used to pave the borough of McKees Rocks.

Cement company now at the base of the quarried out bluff. Note the train tracks in front of it – these are the railroad tracks (still in use) that show up in Figure 1.

We climbed up to the top of the bluff hoping that there still might be a remnant of McKees Rocks Mound still present. Unfortunately, whenever the stone was quarried out of the bluff it also destroyed what remained of McKees Rocks Mound. The edge of the bluff is now used to store materials that are fed into the cement production facility at the base of the bluff.

The railroad tracks that are shown in the 1896 photograph around the base of the bluff still exist. However, they are no longer at the base of the bluff. The rock was quarried out as noted above. Later a cement company built a complex at the base of the bluff. Based on the 1896 photograph of the mound, it would have been located on top of the bluff over top of what is now the cement company.

Bluff top edge showing the storage of materials used to make cement with the conveyor belt that takes it to the mixer in the upper right.

Nothing now remains of the largest mound from Western Pennsylvania, McKees Rocks Mound. What we know about it is based only on the 1896 excavations by Gerrodette for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. It is lucky that Gerrodette conducted excavations when he did, otherwise no knowledge, except the existence of the mound, would remain. Sometime during the 20th century the mound was destroyed during quarrying work on the bluff. The cement company developed the area after the mound was already destroyed, also in the 20th century. Visitors to the area today can see the general area where the mound was built, but will not be able to see any of the actual mound.

References for the excavation of McKees Rocks Mound

Carpenter, E. S.

1949 The Ancient Mounds of Pennsylvania, Vol. 1 and 2. on file at the Section of Archaeology, The State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg.

1951 Tumuli in Southwestern Pennsylvania. American Antiquity 16(4):329-346.

Dragoo, D. W.

1963 Mounds for the Dead: an Analysis of the Adena Culture. Annals of Carnegie Museum Vol. 37, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

McMichael, E. V.

1956 An Analysis of McKees Rocks Mound, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 26(3-4):128-151.

Swauger, James L.

1940 A review of F. H. Gerodette’s Notes on the Excavtion of McKees Rocks Mound. Pennsylvania Archaeologist 20(1):8-10.