Knowing I’d need to write a post for Thanksgiving week, I went to my favorite internet search engine and typed in “Thanksgiving and Pennsylvania”. Among the hundreds of results was one for a Pennsylvania Historical Marker. Really? We have a marker related to Thanksgiving?

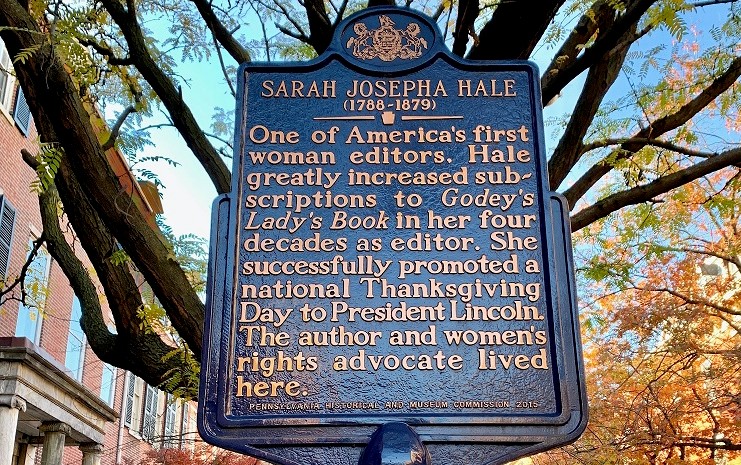

In 2015, PHMC dedicated a marker to Sarah Josepha Hale at 922 Spruce Street, one of her homes while living in Philadelphia. I was intrigued by this line on the marker: “She successfully promoted a national Thanksgiving Day to President Lincoln.” Why had I never heard of this before?

Sarah Josepha Hale

Born in Newport, NH, Sarah Joshepa Hale (1788-1879) was home-schooled and largely self-taught as a child. She was a teacher for a few years before marrying lawyer David Hale in 1813. Sarah and David had five children before he died prematurely in 1822.

Some of her accomplishments include:

- Hale published her first set of poems in 1823, titled The Genius of Oblivion; she would go on to publish close to fifty works by the time she died, including Northwood: Life North and South (1827), making her one of the first novelists to write a book about slavery.

- From 1828 to 1836, Hale served as editor of Ladies’ Magazine; beginning in 1837 and for the next forty years, Hale was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book and became the Martha Stewart of her time. In addition to fashion-watching, morality-promoting, and taste-making, Hale used her time with Godey’s to advocate for education and employment for women and to elevate American writers.

- She founded the Seaman’s Aid Society in Boston in 1833 and helped found Vassar College in NY. She also financially and vocally supported many efforts to commemorate American independence such as the preservation of Mount Vernon and the completion of Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument.

- Hale also partially wrote and much publicized the now-famous nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

Creating the National Thanksgiving Holiday

Most children are usually taught in elementary school that the first Thanksgiving took place in Massachusetts in 1621 when colonists and Native Americans came together for a joyous feast.

We know now that isn’t quite how it happened. I’m not going to delve into that complicated history here, but there are some great articles that discuss the origins and realities of the first Thanksgivings, like this one from the New York Times and this one from the New Yorker.

Efforts to mark a holiday of “thanksgiving” go way back in American history. For example, in 1781 and 1783, the Continental Congress declared national days of thanksgiving after decisive Revolutionary Way victories. George Washington had proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving on October 3, 1789, and John Adams did a few years later.

Until 1863, Thanksgiving was celebrated primarily in New England, where each state set their own dates; it was rarely, if ever, celebrated in the south. Pennsylvania’s governors had made ad-hoc declarations of Thanksgiving in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In Philadelphia, celebrations involved fancy family dinners and church for middle- and upper-class Philadelphians and parades and street celebrations for working-class ones.

From her home in Philadelphia, Sarah Josepha Hale started a letter-writing campaign in 1846 advocating for a “national day of thanksgiving.” She believed the national holiday would “be a great and sanctifying promoter of the national spirit.”

For seventeen years, Hale wrote to every American president as well as governors of states and territories, military leaders, and “ministers abroad” for endorsement of her “Thanksgiving Plan.” While she had the support of state and other leaders, Presidents Taylor, Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan never embraced the idea.

In 1863, Hale was finally successful in getting President Lincoln’s attention. Lincoln embraced the prospect of a new national holiday as a unifying opportunity for a country torn apart by the Civil War. On October 3, 1863, not long after the Union victory at Gettysburg, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the last Thursday in November “as a day of Thanksgiving.”

The proclamation begins with a list of “gracious gifts” Americans have to be thankful for, like peace with foreign nations, continuity and growth of industry and agriculture, and growing population, despite the death, ravages, and divisiveness of civil war. He said, “It has seemed to me fit and proper that they [those gracious gifts] should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People.”

Fourth Thursday in November

From 1863 to 1941, American presidents issued an annual Thanksgiving Day proclamation, setting the date for that year. In 1941, FDR signed Public Law 77-379 that set Thanksgiving as the fourth Thursday in November and made the day an annual federal holiday.

Since then, friends and families have been gathering around turkey dinners to eat too much food, watch too much football, and rest up for the holiday season that’s right around the corner.

Comment Policy

PHMC welcomes and encourages topic-related comments on this blog. PHMC reserves the right to remove comments that in PHMC’s discretion do not follow participation guidelines.

Commenters and Comments shall be related to the blog post topic and respectful of others who use this site.

Commenters and Comments shall not: use language that is offensive, inflammatory or provocative (this includes, but is not limited to, using profanity, obscene, or vulgar comments); disparage other commenters or people; condone illegal activity; identify the location of known or suspected archeological sites; post personal information in comments such as addresses, phone numbers, e-mail addresses or other contact details, which may relate to you or other individuals; impersonate or falsely claim to represent a person or an organization; make any commercial endorsement or promotion of any product, service or publication.

If you would like to comment on other topics not related to this blog post but related to PHMC, please fill out the PHMC Contact Us Form.