In 2016, the preservation community has been looking back over the past 50 years to reflect upon the legacy of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. The legislation laid the groundwork for the tools and strategies of preservation. For Pennsylvania, 2016 also marks the beginning of a multi-year planning process to look forward over the next five years (and beyond) through the development of a new Statewide Historic Preservation Plan. I had the chance to look around at the recent American Planning Association – Pennsylvania Chapter (APA-PA for short) conference and it got me thinking about how preservation is connecting to the bigger planning world.

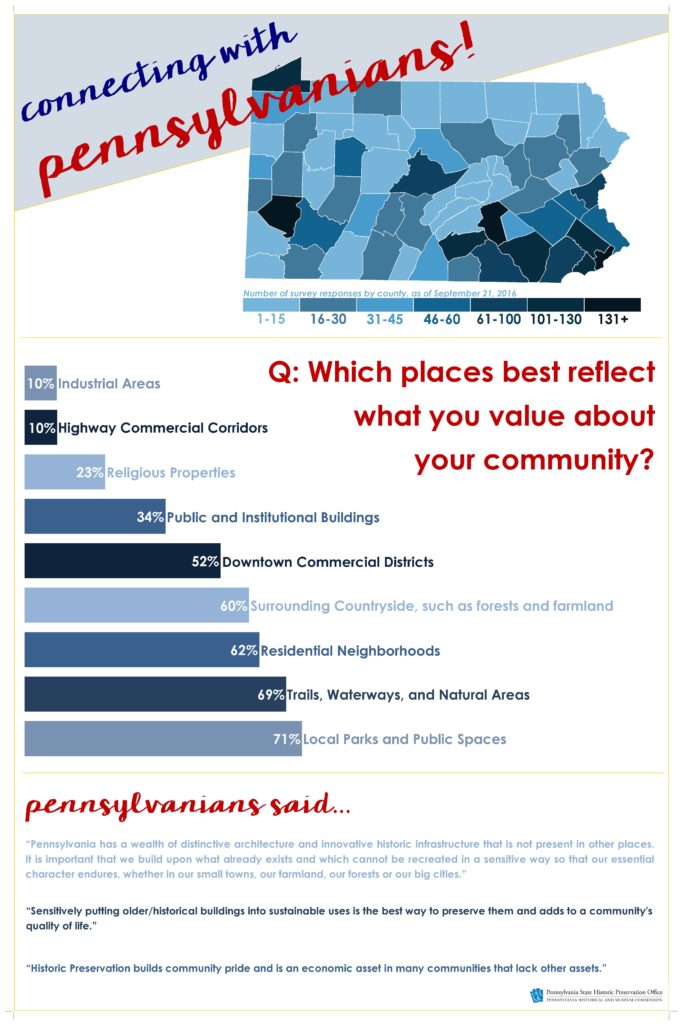

During the planning process for the current Preservation Plan, our public survey uncovered some fascinating links between how preservation of cultural resources, and conservation of the natural environment are interpreted. While organizations, funding, tools, and legislation differ, Pennsylvanians appear to see little distinction between the results of both ‘worlds’ and the beneficial impact on their communities. Perhaps it’s not a surprise to some. After all, the Pennsylvania Constitution conveys both jointly when stating that “the people have a right to…the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic, and esthetic values of the environment.”

Connecting with Communities for the Next Statewide Plan

When asked in our public survey, “What places best reflect what you value about your community?” the top two statewide responses were “trails, waterways, or natural areas” and “local parks or public spaces.” Recently, when the PA Department of Conservation & Natural Resources (DCNR) developed the Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (‘SCORP’), “visiting historic sites” was ranked as the #2 outdoor recreation activity. It’s fair to say that the two ‘worlds’ are closely aligned when viewed by the public. For example, some Pennsylvanians might visit Pine Grove Furnace State Park to learn of the site’s rich industrial history, or visit Conrad Weiser Homestead state historic site to enjoy a picnic and toss a Frisbee to their dog.

Here is what Pennsylvanians have told us about they value in their communities.

The conservation /natural resource community is not our only ally and partner, however.

In the past, statewide preservation plans have been largely informed by groups and citizens with whom the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) typically interacts on a regular basis. Input from our partners, like DCNR, is always very much appreciated. However, in order to help build a stronger heritage coalition for the future, we need to reach out farther so we identified connecting to non-traditional preservation communities a priority in the current planning process.. It’s no secret that ‘traditional preservation’ has difficultly connecting with the average citizen. To bridge that gap, historic preservationists earnestly need to look around for those doing similar work. We must identify those “communities” with whom we share similar goals and results, even though we may not speak the same jargon or walk along the same paths to our common destination. The Planning community is one such example.

At last month’s PA Chapter of the American Planning Association (APA PA) 2016 Annual Conference in Allentown, I joined the planning community and learned where planners are working, what they are working on, and where they see the future of their field heading. (I strongly recommend to all preservationists/heritage conservationists to attend future planning conferences, by the way, as well as recommend that planners attend preservation conferences.) I was pleasantly surprised by the wide variety of session, workshop, and lecture topics, and what was even more exciting was that the majority of them incorporated some underlying theme of preservation, preservation planning, or natural/cultural based place-making.

Topics included: the planned revitalization of the historic 30th Street Station and surrounding Philadelphia neighborhood; storefront façade improvements to revive historic commercial corridors; a large cultural landscape planning study to re-vision historic industrial sites and towns; the integration of hazard planning into comprehensive plans, with a nod to planning for historic resources damaged by disasters; and re-imagining the planning process to ensure implementable goals and successes for communities, something very important as we develop the statewide preservation plan. It was clear that preservation is playing a significant role in community planning toolkits.

The conference also included the Chapter’s annual awards ceremony which recognizes plans, planners, and community leaders, and offers a glimpse into the future direction of the field by highlighting what it chooses to honor as it’s “best and brightest.” Once again, I was pleasantly surprised that several of the award winning projects had strong preservation undertones, including a zoning ordinance from Clymer Borough, Indiana County. Winner of the “Planning Excellence Award – Best Practice,” it was the first ever zoning ordinance for the rural coal town of 1,300 residents. Choosing a form-based code, “the ordinance focuses on a point of pride, the community’s historic, small town, and walkable character, and it minimizes use and other regulations perceived as burdensome.”

In “Think Clymer 2035”, the borough’s comprehensive plan update, notes “The first, and larger component, was development and adoption of a Form Based Code (FBC), designed to preserve the historic character of Clymer’s downtown and surrounding neighborhoods.”

Planning, especially “preservation planning” is among the most strategic tools that preservation has, which is evident by the collaboration and outreach done by the SHPO’s regional Community Preservation Coordinators. After all, planning for the future of the past before it is threatened offers a greater chance of long-term success, greater buy-in from the community who worked so hard to develop the plan, and greater cohesion with the community’s larger planned vision and needs. Such a relationship is mutually beneficial.

Cultural resources offer planners truly unique and economically viable place-making opportunities. Communities all over Pennsylvania are capitalizing on their cultural/heritage resources; whether it is a re-envisioned industrial site, a historic downtown commercial core, a local or regional rail trail, or vast swaths of natural/scenic landscapes dotted with tourist friendly historic communities and preserved and productive agricultural land. This “heritage-planning” relationship has long existed, in some places to great success, but it and its potential has often gone unrecognized.

The Planning and Conservation worlds are just two examples of allied fields. Preservation can be found in numerous fields, such as Landscape Architecture, Sustainability, and Art, to name a few more. Ultimately, we all share similar goals and visions related to our communities and their vitality, establishing and maintaining a unique sense of place, and aims to improve the quality of life for all. Preservation should continue to look back at where the movement has been, and forward to where it could go. However, to ensure creative and successful strategies and outcomes long into the future, it must look around.

Leave a Reply