Last month we talked about how researching a place’s history and physical context factors into hazard planning, and what kinds of building elements are most at risk. This week’s post focuses on taking action and what can be done to protect historic places and their features.

There is so much information to share with you about the conclusion of PA SHPO’s Disaster Planning for Historic Properties initiative that we had to write it over two posts. If you need a refresher about this great project, take a quick read of the Part 1 post last month.

Bedford County, East Providence Twp, 627 Jackson Mill Rd.; Jackson Mills, 012149, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

How do we protect this wide variety of historic buildings with different features from different hazards?

Before we answer that question, it is important to understand what is appropriate within Federal, state, and local historic preservation-related regulations and guidelines. As a regular reader of this blog, you are probably familiar with the National Register of Historic Places. Historic resources eligible for listing on the National Register include districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects. Being listed, or even considered eligible for listing, on the National Register does not protect a property from damages, but it can qualify properties for grants, loans, and tax incentives.

Federal

The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties are common sense historic preservation principles communicated in easy to understand language and concepts. They promote historic preservation best practices for maintaining, repairing, replacing, and altering historic places and historic materials. There are four distinct approaches to the treatment of historic properties: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction, and each have their own set of Standards.

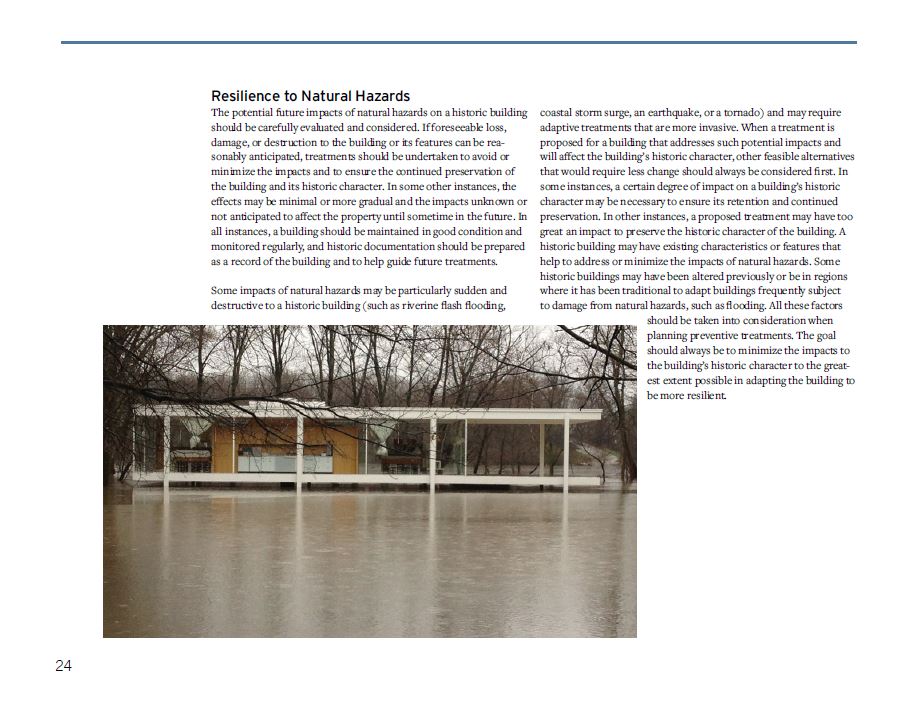

Each set of Standards has a companion Guidelines document that offers general design and technical recommendations for applying the appropriate Standard to a historic property. The National Park Service’s Guidelines specifically address resilience to natural hazards on page 24, noting that hazard mitigation actions should “minimize the impacts to the building’s historic character to the greatest extent possible in adapting the building to be more resilient.”

From the National Park Service’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Historic Properties.

PA SHPO reviews projects involving National Register-listed properties that are funded with federal money (even as a pass-through to a state agency), through the Historic Preservation Fund, and/or use the federal historic tax credit program, to evaluate whether or not the work meets the Standards.

State

In Pennsylvania, the History Code provides some provisions for PA SHPO to review projects involving National Register properties that use state money. Work funded by PHMC, like projects funded through the Keystone Historic Preservation Grants, and those using the state’s Historic Preservation Tax Credit, are also evaluated to determine if the work meets the Standards.

Local

Historic preservation-related ordinances and regulations at the local level vary between municipalities. At the local level, Historic and Architectural Review Boards (HARBS) or Historical Commissions have some level of review over changes to historic properties in their jurisdiction (these are typically identified on an inventory or list of properties and do not need to be listed on the National Register). Examples in the study area range from the absence of formal county or local preservation ordinances and regulations in Cameron County, to robust design review requirements in historic districts in Monroe County, Bedford County, and Philadelphia. For a more in-depth discussion of PA SHPO’s relationship with HARBs, take a look at Cory Kegerise’s post from 2014.

Feature-Specific Actions

In addition to holistically developing hazard mitigation actions for representative historic properties and typologies, hazard mitigation strategies can also be categorized by the specific architectural features that those actions affect. Even within period-specific building styles, individual features and buildings’ relationship to the ground can vary greatly, so feature-specific actions could be more applicable to a much wider array of properties than those selected as representative of particular styles.

Examples of recommended preservation-based hazard mitigation actions and their associated features include:

Entrances at or Below Grade

- Install a temporary flood shield to reinforce at or below grade access doors when flooding is expected.

Basements/Crawl Spaces

- Where historic materials have been replaced with modern materials, “wet floodproof” the basement with flood damage-resistant materials and install “check valves” to prevent water from backing into the drains of the building.

Historic Windows and Doors

- Ensure that historic doors and windows are water tight. Repair damage and replace only if beyond repair. If replacement is necessary, replace in-kind or with a compatible material in consultation with PA SHPO.

Porches

- Inspect porch and porch posts/columns for water damage and sound connections of porch features regularly. Replace porch components damaged beyond repair in kind, and in consultation with PA SHPO if considering not using in-kind materials.

Cameron County, Driftwood Borough, PA-555; Barley Property, 105871.001, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

Foundations

- Patch and repair the foundation in kind or with appropriate, compatible materials only if in-kind materials are not available, in consultation with PA SHPO.

Roofs

- Inspect roofing materials and repair damage regularly. Replace roofing materials in kind that were damaged beyond repair with compatible materials if in-kind materials are not available. Inspect roof for damage as soon as feasible following wind events. Consult with PA SHPO if not using in-kind materials.

Site Drainage

- Evaluate the functionality of drainage features such as gutters and downspouts to ensure proper connections and to ensure roof runoff is being directed away from the building.

Regular Maintenance

One of the simplest ways to protect a historic property is to practice good maintenance. Lack of consistent maintenance can result in historic materials deteriorating and leave historic buildings at greater risk to water and wind damage in a storm or natural disaster. For example, peeling paint exposes wood siding to excess moisture which can accelerate deterioration, while weakened connection points like those in a cornice can cause poorly maintained detailing to be at increased vulnerability to wind, rain, and falling tree limbs.

Bedford County, Harrison Twp, 122 Election House Rd.; Harrison Twp Election House, 011519, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

Philadelphia, 2307 Sansom St.; Workingman’s house, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

Proper maintenance starts with knowing your building’s current condition so that you can recognize if something changes or deteriorates. Regularly inspect the outside of your building to ensure the daubing, or chinking, between logs on a log building is in good repair or that at-grade windows form a complete seal, helps minimize the risk of the building being exposed to water and wind damages.

Bedford County, Bedford Twp, 2138 US-220 BUS; Log House, 023077.0003, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

2600 block of Pine Street, photo taken by SHPO staff 2018.

Property Sheets

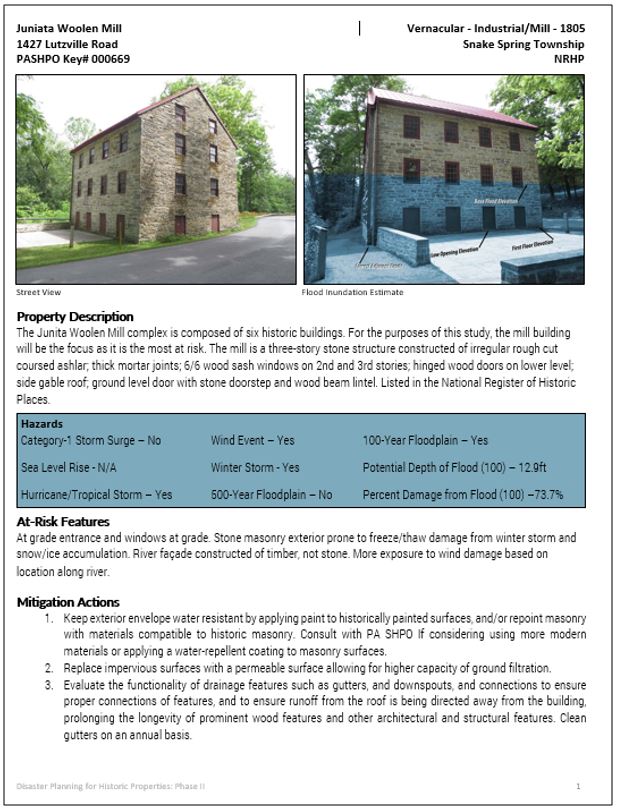

To quickly illustrate the hazards and potential hazard mitigation measures that could impact a property, there is a ‘property sheet’ (below) for each of the representative properties in Bedford, Cameron, and Monroe Counties, and for the building typologies in Philadelphia.

Whenever and wherever possible, low-impact hazard mitigation strategies were developed to minimize potential impacts on historic material. Some aggressive hazard mitigation actions, such as moving or elevating a building, are occasionally recommended and could involve some level of review.

The federal, state, and local regulations were consulted prior to recommending specific changes to historic properties. Some of the hazard mitigation actions proposed in this project would be subject to review by a Historic Architecture Review Board (HARB), the PA SHPO, and/or NPS prior to implementation.

The property sheets created for this project address a diverse range of building forms, styles, conditions, and associated hazard mitigation actions. While these sheets were not created for every individual property at risk in the pilot counties, this diversity is intended to be representative enough to help anyone determine appropriate preservation-based hazard mitigation actions for their own at-risk properties.

Each property sheet includes:

- elevation and hazard-related information from the Phase I survey forms,

- results of the GIS analysis including estimated flood depth during a 100-year flood event,

- architectural considerations and at-risk features,

- photos that illustrate the property,

- a list of recommended sensitive hazard mitigation actions based on the building’s style and historic features

Example Property Sheet

Although actions were developed primarily for buildings, the pilot counties hold many unique historic resources including covered bridges in Bedford County and coke ovens in Cameron County that are also addressed.

Bedford County, Londonberry Twp, Kennels Mill Rd.; Palo Alto/Fischtner Bridge, 050717, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

Cameron County, Lumber twp, CCC Memorial Highway; coke oven near Sterling Run School House, 905017, Phase 1 photo by AECOM.

The common questions

One of the most common questions fielded from county residents and historic property owners while developing final County reports is, “Are these changes mandatory?” That question is then usually followed closely with, “How are we supposed to pay for all of this?”

These hazard mitigation actions are not mandatory. They are meant to be recommendations to help extend the lifetime of irreplaceable historic properties by protecting them from the impacts of natural hazards. As for funding, these types of projects could be funded through several sources ranging from countywide Federal grants to private or independent preservation awards. Securing funding is always a difficult part of any project but determining which kinds of projects should be prioritized for future funding solicitations in a valuable first step. The report also includes a table that identifies potential funding sources for the property owners’ reference.

What’s next

While our work in these four pilot counties is coming to a conclusion, rest assured that this is not the end. PA SHPO is in the process of developing survey and other projects for at-risk properties in additional counties, and we will continue to work with the pilot counties and PEMA to ensure that historic resources are addressed during disaster planning.

While it’s probably not feasible to protect every historic resource from every hazard, focusing on the most at-risk properties and the most likely hazards may be the most effective way to safeguard Pennsylvania’s physical heritage into the future.

Whether you are evaluating a single property or an entire community, implementing a hazard mitigation project for historic resources requires special considerations. For more information on how to implement a Disaster Planning for Historic Resources project in your area, or for further assistance regarding potential funding sources, contact PA SHPO at jgardosik@pa.gov or 717.787.0771. Follow PA SHPO on Facebook and Twitter and stay tuned to this very blog for future updates on the integration of historic preservation and hazard mitigation efforts across the commonwealth!

This week’s post was written by Ashley Samonisky of Vision Planning & Consulting, LLC. Ms. Samonisky is a project manager and lead planner for Vision Planning and Consulting. She has over seven years of emergency management and planning experience including: hazard mitigation, preparedness planning, GIS, public outreach and education. She serves as project manager on cultural resource/hazard mitigation projects. Ms. Samonisky prepares mitigation, preparedness, and recovery plans for communities throughout the Mid-Atlantic. Ms. Samonisky received her Bachelor’s in Emergency Management from Maryland and completed a second Bachelor’s from Salisbury University in Geography. She currently serves on the Maryland State Geographic Information Committee (MSGIC) as the Outreach Sub-Committee Chair.

Leave a Reply